The American Almanac and the Astrology Factor

by Keith A. Cerniglia NINETEENTH CENTURY LITERARY HISTORIAN Moses Coit Tyler, in his 1881 survey A History of American Literature, assigned the almanac to polar ends of the early American mind. Having long suffered literary scorn, the almanac was, in Tyler's appraisal, the "most despised, most prolific, most indispensable of books, which every man uses, and no man praises." It was, Tyler continued, "… the very quack, clown, pack-horse, and pariah" of American literature, but also "the supreme and only literary necessity -- preferable even to the Bible or daily newspaper.1 While Tyler hinted at a kind of perpetuating legacy of almanacs ("the one universal book of modern literature"), scholars such as Bernard Capp and Herbert Leventhal buried the persuasive almanac beside the persuasive astrological chart sometime prior to the dawn of the eighteenth century.2 That said, the preponderance of almanacs in the eighteenth century -- when Boston supplanted Cambridge as handmaiden to the American almanac by way of establishing independent printing presses -- suggests that no successful effort was made to eliminate them.

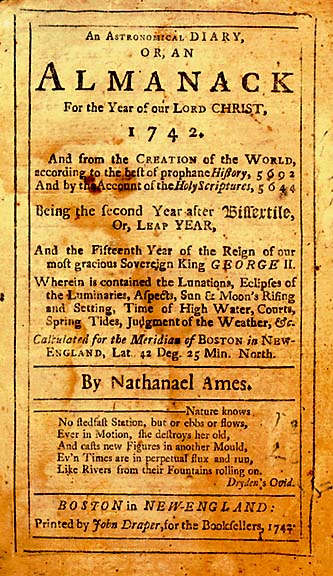

An early American Almanac

It has been argued that astrology and almanacs enjoyed a symbiotic relationship in which each was fitted to serve utilitarian necessity.3 The relationship appears to have been pronounced in Europe, where almanacs emerged as a reflection of the beliefs and methodologies of the early modern period. American almanacs, on the other hand, largely have been cast as weak imitations of their European progenitors and as not playing a great role in contouring religious, social and intellectual lines. Capp, whose comprehensive study of European almanacs spans three centuries, concedes that the rise of the American almanac ran concurrent with the decay of astrology. The American almanac thus, Capp asserts, "naturally evolved in a different direction."4 One question that requires our attention is this: Why shouldn't the American almanac in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have opted to take a direction different from that of its English, French or Hanoverian forbears? Could that direction, moreover, been developed more consciously and actively rather than 'naturally' and passively? Lastly, what effect did the American almanac have on the colonial mind? The purpose of this undertaking is to trace a clear expansion of thought that did not necessarily run counter to popular religion but instead offered alternatives to the ways early Americans perceived their world. The American almanac, of European antecedence but differing in function, shall be used as a determining factor that elicited awareness of the emerging study of astrology. The science of astrology, which almanacs granted mass exposure that cut a swath across class and culture lines in early America, helped signal the encroachment of an increasingly secular world."A BRIEFE HISTORY OF ALMANACKS" IN WORLDS OLD AND NEW How are the mighty fallen! It was not always thus. Far away in the dim vista of the past this humble vehicle of general knowledge was an honored guest at every fireside; the chimney corner was its throne and its well-thumbed leaves gave evidence of the estimation in which it was held. -- Samuel Briggs on almanacs, 1891 5THE HISTORY OF WRITTEN ALMANACS has been traced to the second century of the common era, when Greeks from Alexandria began recording observations in organized form. The first printed almanac dates to 1457 (printed by Gutenberg in Mentz). In 1660s London, sales averaged about 400,000 copies annually.6 As Capp suggests, the almanac's value to Elizabethan and Stuart England was not rooted in any lofty literary quality. The almanac found its way into the hands of the public, discerning and otherwise, because it covered a range of material "cheaply and concisely."7 This was a carryover of the English almanac in America, as well. The high-water mark of English almanacs has been recognized as the years between 1640 and 1700, when the genre diversified by exploring sociopolitical and religious issues.8 During the Elizabethan period, the English almanac began to assume the format we are familiar with today. A principal section included a calendar and was lavishly illustrated with planetary movements. Integral to the English almanac was the 'Zodiac Man,' a figure that depicted various parts of the body as correspondent to astrological readings. Finally, the prognostications (or "predictions") index covered four quarters of a calendar year with weather reports, medical notes and farming information accordingly assigned to that particular portion of the year. These were standard features of the English almanac, though some were refined and modified over time.9 Capp and other scholars indicate that almanac-makers soon opted for regionalization, which allowed the authors to address the specific needs and interests of their communities. Many almanacs proved they were not too exalted for dull or uninspiring doggerel verse, even if the poetry appertained to medical advice.10 Likewise, some almanacs demonstrated sensationalism was not beneath their authors. Far-fetched prophesies, baseless political speculation and acidic social commentary could be found even in the most profitable publications. By the end of the Stuart period, English almanac-makers distressed over how to reach the wide and divergent tastes of the London class system, while at the same time, remain committed to work of a higher quality. Also, the almanac author had a vague notion at best of what the public desired most. "Almanacs sought to fill many roles," Capp writes, "and it is difficult to determine which section the buyer felt to be most important."11 Of the extant English almanacs from the Elizabethan and Stuart periods, the majority was property of landed gentry or professional tradesmen, though it is clear their readership was exclusive of class or trade.12 The American almanac indeed evolved along different lines and flourished under ideal circumstances. No newspaper existed in the colonies before 1704 (the Boston News-Letter) and no magazine before 1740 (Andrew Bradford's The American Magazine). The first colonial almanac can be traced to 1639, when a publication called the Almanack Calculated for New England, by Mr. [William] Pierce, Mariner was printed on the Harvard University Press, then just a year old. Printed in 16-page book form, these early almanacs included a title page, information on eclipses, the annual calendar and notes on the courts.13 Prominent to the early American almanac was a riff from the European 'Zodiac Man.' Even readers with only crude literacy skills could use the 'Zodiac Man' to connect parts of the body with signs of the horoscope or prescribe cures for nagging diseases.14 In American almanacs, this feature went by a variety of names, including homo signorum, the Man of Signs, moon's man, the "naked man" or "anatomy." Whereas the European almanac experimented with modifications over the course of its long and illustrated history, the American version adhered to established conventions. "Any later departure from established formal would risk the loss of readers… who expected to find certain items in certain places," researcher Marion Stowell suggests.15 It was not the format, though, which made the colonial almanac the most successful vehicle of the secular literary tradition in the New World. Seventeenth century colonial almanacs found an immediate audience. The Cambridge (Massachusetts) printing press produced 157 books between 1639 -- the birth year of the American almanac -- and 1670. In this span of four decades, almanacs were exceeded in publication only by religious books, tracts and sermons.16 This is remarkable when considering the vitality of religion in early America. In terms of numbers alone, almanacs were published in far greater quantity than all other books combined in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.17 How many almanacs were in print in this span of 170 years? Charles Evans' American Bibliography, a 12-volume work that took him 31 years to complete, lists more than 1,100 different almanacs published between 1639 and 1799. 18 Historically, the American almanac, while clearly English in origin, occupies a unique place in the story of our literary culture. It has been dismissed as derivative, ordinary and even plagiaristic, but the almanac has played a great role in broadening the scope of American social and intellectual horizons. It will be argued in succeeding pages that the American almanac, which reached the hands of colonial Americans in greater number than any religious book, made inroads into a growing secular society through the selected so-called "occult sciences" of astrology.

"WHEREIN IS CONTAINED ACCOUNTS OF ASTROLOGYE:" COPERNICAN SCIENCE CROSSES THE ATLANTIC Some Degree of Superstition, mixed with and overbalanced by the Light and Influence of Religion, leads Men on to a greater Degree of Goodness; so in Astrology, the Superstition of which in Politicks, with good Sense and Learning, and the Use of all Lawful means, may lead Men on to Greatness.BEFORE DISCUSSING HOW AMERICAN ALMANACS raised an awareness of astrology in the colonies and helped change the texture of society, it is necessary to identify astrological science. In its construction, astrology was an ordered, methodical attempt to understand natural phenomena. Existing scientific laws, tried and true from the ancients on through Copernicus and Kepler and later Newton, were used prudently as a guide. Astrology as a practical science was a means prescribed to meet rational ends, which makes its alleged deterioration in the Age of Reason puzzling.22 The invention of the telescope in the latter half of the eighteenth century altered the discipline dramatically, and from a purely technical point of view. Scientists intrigued with cosmology discarded the astrolabe in favor of the telescope, which presumably helped them reach more rational results. Born of eastern origins, astrology in the early modern period was a study of solar eclipses, lunar eclipses and planetary movements. The calculating astrologer, who cultivated new solutions and new inquiries alike at rigorous research institutions such as Oxford, Cambridge and Trinity, sought a more revealing utility for his science. Did the planets share relationships? Were the planets in cooperation or were they in opposition? Could these relationships create effects that altered events on earth? These all were challenging questions for the astrologer, but the excitement of using knowledge gained from critically watching the skies pressed his science to new practical heights. These ambitions, thought to intersect with existing dogma created by the religious superstructure, met resistance and fierce condemnation from the church. The practice of astrology drove a deep cleft between its study and Christianity. Given the climate of the times and the leverage religiosity enjoyed over all things secular, derision of astrology seems natural. It was pointed out in scorn that the very term "zodiac" comes from the Greek for "band of animals."23 Thomas More's Utopians were less than convinced: "But as for astrology - friendships and quarrels between the planets, fortune-telling by the stars and all the rest of that humbug - they've never even dreamt of such a thing."24 The frosty disposition of the church toward astrology also had an effect on how it was received and pursued by the public. One Joseph Blagrave (in England) admitted in 1673 that clients who wished to remain anonymous consulted him for astrological readings, fearing the ire of the church. In spite of the aspirations of English astrologer Robert Boyle and others who believed astrology complemented Christianity, the discipline largely was received with castigation and outright mockery. Copernican science would carry this cumbersome baggage en route to the shores of the New World. Daniel Leeds informs his readers in 1697 that some of his "former friends" had been "influenced against me by their Ministers, [and] for my zeal against their Falsehoods and grose [sic] Notions have a watchful eye upon me in that respect."25 It is doubtful that the majority of seventeenth and eighteenth century astrologers, in worlds old and new, applied their science in an attempt to displace God or anticipate how God imposed His will on earth. Astrologers, however, could be separated by their ideologies, not unlike politicians or clergymen of the time. Some were conservative, distancing themselves from the potential disapproval of the church, or from the biting pen of satiricists such as Jonathan Swift (who compiled a mock almanac for 1708). Others were moderate, trying to stay in compliance with the stern morality of the church, but at the same time, endeavoring to advance their craft. Radical astrologers such as William Lilly and Nathaniel Culpeper of England brazenly asserted that God used the cosmos to undermine the monarchy and the church.26 A division in ideology likewise existed among astrology enthusiasts in the colonies who responded to similar currents of society and feared similar repercussions. Regardless of how little or how far astrologers desired to press their art, astrology in its advancement presented alternative choices. In a culture where God was not to be understood but adored, and where acts of providence should be accepted for no other reason than that they were guided by God's judgment, astrology presented fresh perspectives - in worlds old and new. "The need to form a safer religion, purged of enthusiasm, was widely recognized," Capp offers.27 New syntheses for decoding how God worked thus moved into the colonial mind. Astrologers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were not searching for reasons why God imposed His will on earth; they were searching for how acts of divine intervention could be explained. The study of astrology in Europe and colonial America was split into two schools of thought: natural and judicial. Natural astrology, which was accepted by Calvin and even many of astrology's harshest critics, was defined by the observation of planetary movements and their influence on weather, farming and medicine.28 Judicial astrology probed into far more complex matters. In much of the literature on the subject, it is interesting to note that explanations of judicial astrology use the decidedly soft verb "attempt." Essentially, making predictions and casting horoscopes, even if gleaned from serious scientific observation, were trials subject to human error. Perhaps it is this that most aggravated the religiously inclined; they believed nothing God did was an "attempt" of any sort. Judicial astrology was a bold extension of natural astrology, and the two branches found equal comfort in American almanacs. Arguably, astrologers and adherents of astrology thought judicial astrology to be more utilitarian than its more benign companion branch. If astrological science could be used to help the colonial farmer determine which months would be kindest to his crop, why shouldn't it then be used to portend floods, famines, fires or smallpox epidemics? The colonial American saw astrology as a valuable instrument in his vocational and personal life. William Byrd wrote in his diary that he consulted a "conjuror called Old Abram [who]… gave me hope that my mistress would be kind again."29 Colonel London Carter recorded in his eighteenth century diary that his field was "[a]s dry everything as Usual, and nothing has grown this whole week. Its [sic] my 3d planet that governs, and I shall not this year amount to a groat."30 Astrology had discovered applications in the colonies; it needed only a vehicle to further spread its practicable utilities. Colonial almanacs, like astrology itself, were divided in construction. There were almanacs that were practical in development (intended to supplement the studies of agriculture and medicine) and those that were serious works of judicial astrology. Some almanac-makers who subscribed to judicial astrology were hesitant to be specific about their prognostications since they believed readers abused the information. Daniel Leeds, an author who had been expelled from Quaker society a decade prior, asserted in 1698 that lunar and solar eclipses had an effect on world events, but he would not "assign and limit their effects to any particular place" because readers were "too much led astray… by many of their Teachers."31 Regardless of their nature, it is evident astrology found a real voice in the colonial almanac. Leventhal argues that almanacs' role in opening up the world of astrology was "purely educational."32 Many almanac-makers took this approach, but it can be argued that they would have been delighted if readers could make some functional use of the information they imparted. In his first public effort, the Almanack for 1726, Dr. Nathaniel Ames assumes an instructive approach, and takes pleasure in "…being a friend to all that are Mathematically inclined."33 Ames was a judicial astrology enthusiast, but it is clear he wanted to play to a wide audience. In the Almanack for 1738, Ames cautions his readers that "… I would not have you think that I am a Superstitious Bigot to Judicial Astrology."34 Ames, whose series was continued by his son until 1776 (the elder died in 1764), authored his almanacs in a convivial style that did not look down upon readers from a scientific perch. Ames considered himself a perpetual student of astrology, and assigned a high responsibility to his craft. Ten months before his death, Ames summed up the capacity for understanding that he felt astrology held. It approximates a certain zeal and enthusiasm that matches the passion religious men of the day felt for their theology:-- Dr. Nathaniel Ames, The Almanack for 1764 19

Strange Things this Year will come to pass, I'm told by some Ass-trological Glass, The Birds will sing, and Sheep will bleat, And hungry Folks will want to eat.-- Poor Robin's Almanack, 1690 20

Billy and Dicky, Peggy and Molly must see the Man on the Moon; and when the little child cries, the great one runs for the Almanack, to bless the House with Peace.-- Jacob Taylor, in contempt of almanacs, 1743 21

Astrology has a Philosophical Foundation: the celestial Powers that can and do agitate and move the whole Ocean, have also Force and Ability to change and alter the Fluids and Solids of the humane Body, and that which can alter and change the fluids and Solids of the Body, must also greatly affect and influence the Mind; and that which can and does affect the Mind, has a great Share and Influence in the Actions of Men.35Other early American almanacs excluded entirely the use of judicial astrology, denouncing its practice as impious and heretic. Samuel Danforth's almanac of 1646, the earliest surviving American imprint, did not label months by signs of the zodiac and avoided the traditional Man of Signs and projections of judicial astrology. English almanacs observed holy days (highlighted in red ink) in conjunction with days commemorating important days in the history of the state. Danforth urged a firm departure from this custom. "…[W]e reject them whol[l]y," Danforth wrote piously in 1646, "as superstitious and Anti-[C]hristian, which being built upon rotten foundations, are Idle Idoll [sic] dayes [sic]."36 Danforth adhered to a simplified format that included poetry about New England, monthly calendars and notes on local events. In 1648, one such compilation of notes included a list of "memorable occurrences," which recalled the banishment of Anne Hutchinson "and her errors" to Rhode Island in 1638. 37 Danforth and other producers of the local "religious" almanac, many of the authors Harvard-educated and anticipating a swift promotion to the pulpit, used the almanac to meet prescribed agendas that had nothing to do with astrology. These almanacs can be understood to be extensions of Puritanism; they sought to cleanse and sanitize the English almanac. As scholar David Hall suggests, modification of the traditional English almanac in seventeenth century New England was "deliberate."38 The Elizabethan theologian William Perkins inspired some hostility toward the almanac by assailing it and astrology in equal measure. Perkins ridiculed the use of astrology to predict natural catastrophes, backing up his claims with chapter and verse from scripture. Almanacs, the prominent Puritan decried, fostered "contempt for the providence of God."39 Of their forecasts, Perkins warned that "the judgment of God [is] upon them."40 Perkins admitted that cosmology might reveal something of human existence, but that the stars' importance could not be calculated or understood by man.41 The influence of Perkins and other English critics such as William Fulke, Francis Coxe and Nicholas Allen upon the early Harvard 'philomaths' (as Danforth and his contemporaries in the 'cleaner' almanac business were called) is understandable. The philomath almanac, usually compiled by young students with a scientific bent, made efforts to avoid the vagaries of astrology in favor of strict Newtonian theory. As is customary with the study of science, however, there was always the risk of the young philomath coming too close to the electric fence of entrenched Puritan dogma. The danger of Newton's science intersecting with the lessons of scripture, Stowell contends, "never seemed to enter the minds of Puritan divines."42 The Puritans enjoyed a special advantage: they reserved the right to use astrology -- and almanacs -- in convenient ways. Since Harvard controlled the early printing presses, and since Puritanism commanded early New England society, "… the Puritan's double vision allowed him to interpret cosmic phenomena both as omens of disaster according to God's providence, and as heavenly bodies obeying the natural laws of the universe."43 If the Harvard philomaths' modification of the English almanac was deliberate, then the transformation of American almanacs toward the close of the seventeenth century can be argued to be a post-reaction to those currents. Among those who made early exertions to expose the public to the tenets of traditional Copernican astrology were Zechariah Brigden, Samuel Cheever, Samuel Brackenbury and Massachusetts colonial governor Joseph Dudley. Even the accomplished theologian, scientist and man of letters Cotton Mather was not beyond exploring cometary implications. These were conservative works of astrology, but they revealed that natural astrology was spreading throughout colonial culture, with no organized effort to obliterate it. That a figure such as the luminary Mather would break away from more serious ruminations as soul-saving to probe the skies for some sliver of truth (even if he did not believe it sustained any theological merit) reflected an embrace not only of traditional astrology but also of its transporter - the distinctly American almanac. Mather's body of written work is voluminous and prolific, and it includes some almanac writing. As Samuel Briggs writes, Mather "… ceased on occasion, from [his] combats with Satan, to rejoice the world with an Ephemeris," or the term for an astronomical almanac.44 It is important to emphasize that the shift from natural astrology to judicial astrology, as tracked through almanacs, was not immediate. As late as 1694, two years after the Harvard press at Cambridge discontinued the printing of philomath almanacs, author Thomas Brattle wrote that "[a]strologicall [sic] Predictions… serve only to Delude and Amuse the Vulgar."45 In 1697, New York almanac-maker John Clapp prefaced his annual by reaffirming that he had no desire to "unravel those mysterious Secrets kept close to the Bosom of the great Creator… [as] no Mortal living can prejudge any matter cause thereof."46 Mather made room for cosmology, insofar as it did not encourage moral turpitude, but still wondered that "… it not be absurd to beseech the Readers of an Almanack to become Christian men?"47 In 1683, the 20-year-old Mather made his first incursion into the world of almanacs, voicing a desire to transform "a sorry Almanack" into a "Noble" work of literature.48 Jacob Taylor, an eighteenth century almanac-maker who condemned all variations of astrology, called the science in 1746 a "meer [sic] cheat, a Brat of Babylon, brought forth in Chaldea, a Place Famous for Idolatry."49 Taylor believed a "much inferiour [sic] rate of artists" had emerged and had become "bewitched" by judicial astrology.50 Critics likened bad theology to rubbish they believed were contained in almanacs. Reverend Thomas Robie of Salem, Massachusetts once received the reprimand of an anonymous critic who wrote that Robie's "sermons were only heathenish discourses -- no better Christianity than there was in Tulley." John Tulley was an almanac author and died before the criticism of Robie was written.51 Astrology and almanacs, which have been presented as being mutually beneficial, would not storm onto the cultural scene so easily. Several concurrent developments might have led to the decline of Cambridge Press (Massachusetts) philomath almanacs and the quiet ascent of what we have come to recognize as the 'farmer's almanac.' Printers John Foster, William Bradford, Daniel Leeds and Tulley began successful and innovative series of almanacs, incorporating weather information and the Man of Signs. Foster and Bradford established printing presses in other parts of Massachusetts and in the middle colonies, which facilitated an awareness of astrology in spheres outside Boston.52 Ames, along with Leeds, is credited with having started some of the most well-received almanacs of the eighteenth century. These almanacs helped lead judicial astrology to the forefront of the almanac-reading public for more than 40 years.53 Stowell, in examining more than 500 seventeenth and eighteenth century almanacs, credits Tulley with revolutionizing "the character of the American almanac."54 Tulley's almanacs were a departure from the solemnity of the New England almanacs and were known for their exercise of judicial astrology, as well as crude poems and ribald stories. Gradually, religiosity's stranglehold on the times was becoming less and less pronounced. English historian A.F. Pollard, who published a volume in the Political History of England series in the early twentieth century, intoduced a fascinating theory similar to the "wages-fund theory of the historical process" that illustrates the strengthening of things secular and the weakening of things religious.55 As one might expect, the theory was derived from Newtonian physics and applied to historicism. Pollard reasoned that in any given society, the energy surrounding a single pair of polar devices is preset. Since the energy is fixed, the flow of "social energy" in the direction of one pole is possible only if it is taken away from the other pole.56 For purposes of this study, the two discrete poles are established, of course, as secularity and religiosity. If we test Pollard's theory in regard to the rise of astrology and almanacs against the backdrop of what had been a pious resistance, we may deduct that astrology and almanacs - along with a host of other currents that rose up during the formation of a more rational world - played a role in the displacement of this 'social energy' from one pole to the other. Astrology and almanacs were constantly beset by criticism in the eighteenth century - censure seems as much a part of the discipline as the zodiac itself - but together they built a colonial American audience that was inclusive of class, gender and vocational diversity. Astrology's penetration was steady and faced the same theological resistance it had in mother England, but carved an identity in the colonies durable enough to last well into the eighteenth century. Certainly, astrology was strong enough to persist through the Enlightenment in America, which was as fertile an era as any for a science rooted in rational thought to prosper. It stands to reason that the colonial almanac played an indispensable role in promoting astrology, and vice-versa. It is difficult for the scholar to investigate one without investigating the other, and, thusly, hard to remove one from the scope of view without removing the other. The scholars remain skeptical in assessing astrology's lasting power. Leventhal underscores 1701 as a date when astrology's cracks first began to show, when the tireless Jacob Taylor first launched his powerful attacks against judicial astrology and almanacs.57 In addition, Leventhal suggests that scientists began to discard astrology after acquiring a solid foundation of mathematical knowledge and absorbing innovative Enlightenment thought, such as that found in Newton's Principia.58 How, then, to account for the enormous popularity of Ames' almanacs, for example, which flourished in the mid-eighteenth century? Ames' almanac series, firmly rooted in judicial astrology, sold between 50,000 and 60,000 copies annually.59 A careful review of the sources indicates the scholars have been too hasty to write an obituary for the application of astrology, irrespective of its natural or judicial disposition. Late in the eighteenth century -- during which the researchers have sounded the death knell for astrology -- women, blacks and foreign-born printers had already made their incursions into the world of almanacs and astrology. This appears to reflect even further diversity in, at the very least, basic exposure of astrology. To use another example, Stephen Row Bradley's Astronomical Diary of 1775 almost outsold (2,000 copies) the second-largest circulating colonial newspaper of 1770, William Goddard's Pennsylvania Chronicle (which had 2,500 subscribers).60 How exactly did astrology and the way it was showcased by its benefactor, the almanac, expand the colonial mind? American almanac-makers were writing serious expositions on astrology and cosmological phenomena that struck a distinct appeal within what had been a narrow popular culture. The almanacs were not only being read by individuals who were scientifically inclined, but also by landed gentry and commoners, men and women, and merchants and farmers. We may reason that seventeenth century colonials simply tired of reading and being influenced by the Bible exclusively. There were reasons the average New England personal library was comprised of the Bible, the New England Primer, a collection of sermons -- and a local almanac.61 It provided sophistication, and possibly even an inviting respite from the stern admonitions of printed sermons and the stark immutability of scripture. As Stowell summarizes, "the Bible took care of the hereafter, but the almanac took care of the here … [it] was the layman's to do with as he pleased; he could study it, disagree with it, and scribble [on] it." 62 One can conclude that astrology, for good or bad, offered those exact same options.

Endnotes

1 Herbert Leventhal, In the Shadow of Enlightenment (New York: New York University Press, 1976), p. 23. 2 Ibid. 3 Bernard S. Capp, Astrology and the Popular Press (London: Faber, 1977), p. 291. 4 Ibid., p. 276. 5 Samuel Briggs ed., The Essays, Humor and Poems of Nathaniel Ames (Detroit: Singing Tree Press, 1969), p. 13. 6 Capp, Astrology and the Popular Press, p. 23. 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid., p. 24. 9 Ibid., p. 34. 10 Ibid., p. 35. 11 Ibid., p. 62. 12 Ibid., p. 60. 13 Marion B. Stowell, Early American Almanacs: The Colonial Weekday Bible (New York: B. Franklin, 1977), p. 17. 14 Jon Butler, "Magic, astrology and early American religious heritage, 1600-1760," American Historical Review 84:2 (1979), p. 330 15 Stowell, Early American Almanacs: The Colonial Weekday Bible, p. 19. 16 Ibid., p. x. 17 Ibid. 18 William D. Stahlman, "Astrology in Colonial America: An Extended Inquiry," William and Mary Quarterly 13 (1956), p. 561. 19 Samuel Briggs ed., The Essays, Humor and Poems of Nathaniel Ames, p. 347. 20 Stowell, Early American Almanacs, p. 244. 21 Jacob Taylor (pseudonym?), An Almanack for the Year… 1743 (Philadelphia, 1742). 22 Stahlman, "Astrology in Colonial America: An Extended Inquiry," p. 555. 23 Michael Sims, Darwin's Orchestra: An Almanac of Nature in History and the Arts (New York: Holt, 1997), p. 170. 24 Ibid. 25 Daniel Leeds, An Almanack for the Year… 1697 (New York, 1697). 26 Capp, Astrology and the Popular Press, p. 280. 27 Ibid. 28 Ibid., p. 16. 29 Leventhal, In the Shadow of Enlightenment, p. 56. 30 Ibid., p. 57. 31 Butler, "Magic, astrology and early American religious heritage, 1600-1760," p. 330. 32 Leventhal, p. 23.Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

USMLE Tutors

God Of War Tutors

IB Biology Tutors

IB Environmental Systems and Societies SL Tutors

SSAT Tutors

Pharmacogenomics Tutors

Math Tutors

Microsoft Powerpoint Tutors

General Biology Tutors

ESL Tutors

Trigonometry Tutors

Division Tutors

4th Grade Social Studies Tutors

Stochastic Calculus Tutors

Occupational Hygiene Tutors

Biology Tutors

Oenology Tutors

Reading Tutors

Radical Functions Tutors

Windows Tutors

Popular Test Prep