Tourism and Display in American Amusements

Page 2

Page 1 Greenhalgh notes, "The first Fairs in the twentieth century became obsessed with evolutionary theory in an attempt to give scientific credence to the legalized racism present everywhere in American society. The [Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (1901)] was the extreme case, where the layout of the whole site was intended to show the visitor the shift from low levels of humanity to higher ones. It was hoped the visitor would sense the evolutionary flow of mankind as he/she walked through the Fair."[cxxii] Expositions, often touted an "experience" rather than a "show."[cxxiii] The Midway, a term taken from the 1893 Columbian Exposition, is often the home of the sideshow, the spectacle, and the commodification of culture. Hinsley describes the Midway as, "The eyes of the Midway are those of the fl^aneur, the stroller through the street arcade of human differences, whose experience is not the holistic, integrated ideal of the anthropologist but the segmented, seriatim fleetingness of the modern tourist 'just passing through.'"[cxxiv] However, both on and off the midway, Fairs often "celebrated the ascension of civilized power over nature and primitives."[cxxv] Hinsely points out that by 1890, two traditions of human display were established. The first, the Hagenbeck type, usually made claims to ethnographic authenticity and the second, the Barnum type, often displayed human freaks and oddities.[cxxvi] These two forms of show were not mutually exclusive and exhibits often contained both elements. Of course, the more "educational" exhibits attempted to keep voyeuristic appeal in the shadow of their scientific objective, but nonetheless managed to attract the attention of plenty of tourists both near and far. The Columbian Exposition, for example, attracted over 27 million visitors at a time when the population of the United States was only about 67 million. Expositions became destinations or excursions for the American public, and "public curiosity about other peoples, mediated by the terms of the marketplace, produced an early form of touristic consumption."[cxxvii] Under the guise of science and education, the spectators could witness otherwise forbidden acts and as a result, reinforce proper societal behavior—almost always the antithesis of these performances. Sideshows became one of the most popular forms of entertainment while they seemed to push the boundaries of social acceptance. We could see the sideshow as, "a theater of guts; a viscerally titillating place where performers violate their bodies with spikes, swords, and fire and walk off the platform unharmed," but it was much more.[cxxviii] It was a space where two worlds managed to collide, and "the freak show expressed what Eric Lott calls "the racial unconscious,' implicating cross-cutting desires for difference and superiority—but it also expressed a desire for sameness by identifying freaks as fellow humans."[cxxix] In live exhibits and displays, the spectacle was also a person who existed between reality and performance. Sideshows have been said to, "reflect some aspect of human nature. Here is the mirror of our inner selves. Here are things ugly, curios, admirable and beautiful, each warranted to stir some primal emotion."[cxxx] Thomson writes, "Because [freak] bodies are rare, unique, material, and confounding of cultural categories, they function as magnets to which culture secures its anxieties, questions, and needs at any given moment."[cxxxi] The public interest was further peaked by adding an unusual 'talent' to the act. Freaks and foreigners were often showcased for their abnormality, but their acts were not stagnant. The performers did not just stand idly by onstage, but engaged in various acts of skill, strength, and humor. Otis Jordan, for example, was born with ossified limbs and grew to be a mere 31 inches in height. He propelled his body in a 'hopping' motion by the use of his neck muscles, and was often dressed in costumes that concealed his limbs so that he could be billed as "Otis the Frog Boy".[cxxxii] His 'act' was not just a blatant display of his unique physique, but involved a range of cigarette tricks including the difficult task of rolling, lighting, and smoking a cigarette using only his lips.[cxxxiii] Because of continued disputes from the community regarding the exploitation and demeaning portrayal of disabled people,[cxxxiv] Otis eventually ended up at Coney Island and performed the same act under the more politically correct billing, "The Human Cigarette Factory".[cxxxv] These bodies, whether disabled or marginalized in some manner, were the epitome of early American work ethics. These bodies were commodified, and they were surely not idle. Whether armless, legless, blind, conjoined, or mentally handicapped, these bodies would always manage to perform. The legless would perform acrobatics, the armless would write calligraphy with their toes, the blind would juggle knives, the conjoined would play musical instruments, and the mentally handicapped would cheerfully perform a song or dance. We see the remnants of Marxism and the blossoming of capitalism at its finest. Here, even the disabled work and people were seen as "raw materials".[cxxxvi] Martin-Barbero in his critique of Marxism, suggests that actors that do not represent the popular, such as invalids, are often in conflict with hegemony.[cxxxvii] But, this is not the case with freaks. On the contrary, and quite ironically, what appeared to be the most 'useless bodies' were the exemplary models of American work ethics. Unlike static objects, money was made by turning these individuals into commodities, who were in turn, working to commodify themselves. In regards to the freak, the shift from deviant to normal is not fixed—It ebbs and flows into one another. It is the fluctuating space of uncertainty, or the anomalous boundary, between ordinary and peculiar, that allowed the public to become attracted to these human displays. And it is the ability to traverse these boundaries combined with social constructions of society, that resulted in the extraordinary depictions of the freaks. Thus, the successful commodification of these 'others' was achieved by placing a significant emphasis on this shifting border, and one's place in relation to it. Thompson suggests that the historical changes in "freak discourse genealogy" are framed within the cultural imagination and reflect "a movement from a narrative of the marvelous to a narrative of the deviant....In brief, wonder becomes error."[cxxxviii] The line between visitor and performer is one of the most important, and obvious, aspects of the freak display. Susan Stewart writes, "The viewer of the spectacle is absolutely aware of the distance between self and spectacle....there is no question that there is a gap between the object [freak] and the viewer."[cxxxix] Stewart later defines this gap as a separation, or even hesitation, between the chatter of the 'talker' and the appearance of the freak.[cxl] Hinsley suggests the line between the visitor and performer spaces is always evident, and sometimes quite simple, such as a fence, chain, rope, or bench row, and the placement of the spectator and spectacle is a physical and ideological construction.[cxli] He further proposes that the camera is to the modern tourist as the fence is to the Victorian spectator—for self-definition and distancing.[cxlii]

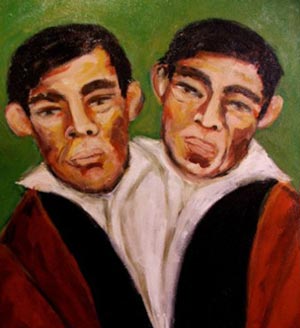

Cheng and Deng

The goal of display is to distance the viewer and place them in a socially constructed position of authority. In his acclaimed study of freaks, Leslie Fiedler writes, "[There is nothing] novel about the mode of presentation, so that after a minute or two we do not know in what town we are, or at what point in our lives. The human oddities on the show are never displayed on our level—the level of reality and the street outside. Most often they stand against a curtain on a draped platform, to which we have to look up...sometimes they are placed in a railed "pit", into which we have to look down..."[cxliii] The pit shows almost always featured a 'geek' show, a cannibal act, or a crazed savage, whereas the balcony shows regularly featured human oddities and acts of talent.[cxliv] These expose the space of performance as a result and reflection of socially constructed views of 'others'. We look down on those lower on the evolutionary chain-whether literally or figuratively, and we do not hesitate to allow ourselves a better view of the curious and strange. We can see a direct attempt to show even the most crass display of human (or sub-human) behavior, while simultaneously invoking feelings of curiosity and pathos in the audience. The audience could delight in the concept of the uncivilized becoming civilized, while satiating their own desire to feel racially and intellectually superior towards the spectacle. It was possible for civilized individuals to become uncivilized, and this, perhaps, kept the public on their toes. One of the most popular sideshow acts involved the 'geek', who was usually a person without any physical or psychological disability (often a drunk) in desperate need of money, and who could subsequently be convinced to eat live chickens, dogs, or other small animals.[cxlv] The geek act was remarkably popular, and could be seen as a symbolic depiction of man turned savage. This act played upon the spectator's fear and fascination regarding the ability to cross the boundary of civilization and enter the world of savages. The spectator aspired to see the savage(s) become assimilated, and equally found fascination in entertaining the idea of a 'civilized' human going mad (i.e. exhibiting 'savage' behavior). But the thought of crossing into the 'other side' was perhaps, too shocking a concept for the spectator. Most sideshows featured the "Ten-in-One", which consisted of at least ten performers with various deformities and skills in a constant cycle of acts. The Ten-in-One promised Ten acts for the price of one, and more importantly boasted "no waiting". The spectator could enter at any given point in the show and when the cycle of acts eventually rotated back to the act in which they entered, they would leave. At first, the viewer appeared to be surrounded by a seemingly unrelated group of freaks, but soon found a connection between these acts—somehow they all appeared to fit together. These radically diverse individuals are citizens of their own (freak) culture, not only within the borders of the exhibition, but among normal citizens outside this territory as well. This "cultural connection" provided those within this community certain regulations, norms, and requirements that result in a form of citizenship. For those outside this sphere, the idea that freaks possess a form of cultural citizenship only increased the need to group these individuals as "others." 'Otherness' in this sense, was a combination of both physical abnormalities and non-western ethnicities. As a result, freaks of all types were assimilated into a pan-freak culture. Much like Andrew Apter's critique of the Pan-African representation of Africa as possessing a homogeneous and unified culture, [cxlvi] we see that freaks, too, are also susceptible to the ever-popular 'blanket' freak designation, and in essence, these individuals were fashioned together in a quasi-freak diaspora. Spectators could attend a sideshow or exhibit and view individuals from a variety of ethnicities. For example, Lia Graf a little person from Germany, Lionel "the Lion-Faced Boy" from Russia, Madame Clofullia "the Bearded Lady of Switzerland", Frank Lentini "the Three Legged Man" from Siracusa, Sicily, Mortado "the Human Fountain" from Germany, Pip and Flip "Twins from Yucatan" (Although actually born in Georgia, USA), and countless others.[cxlvii] It was not merely their physical abnormalities that constituted their 'otherness'. It was a combination of their individual ethnic backgrounds, their abnormalities, talent, or ethnicity. I have suggested that the collectiveness of freaks alone, allow for a certain degree of cultural citizenship, and I have also referred to these individuals as 'others'. Most scholars, when describing the "commodification of otherness" refer to representations of race and gender.[cxlviii] Here, I am using this term liberally. While many of these live exhibits display individuals of foreign ethnicities, it is often the physical abnormality, 'primitiveness', or unusual talent that is presented—all of which are neither a race nor an ethnicity. It is the fabricated race (giants, monkey people, alligator people, etc.) and/or gender (the 'half man/half woman' or 'Zip the what is it?') that is exhibited and commodified. Wax figures emerged again in the 1900's (as well as mummies), and were also exhibited as freaks, such as "The Embalmed Bandit", "The Stone Man", "The Amazing Petrified Man", Floyd Collins, John Wilkes Booth, Notorious Marie O'Day, and Mr. Dinsmoor to name a few.[cxlix] Although, living beings proved to be the most successful "product." Sideshows remained concentrated on narratives of the fantastic, while expositions continued to focus on "progress." In expositions, human oddities existed as the foundation of new knowledge both scientific and anthropological. One such example can be seen in the live display of ceremonial Filipino Bontoc Igorot dancers at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle. Vaughan writes, "Promoters [of the Igorot dancers] ignored government warnings against emphasizing the "savage" spectacle, applying an academic veneer to the exhibit by offering college anthropology courses in "The Growth of Cultural Evolution Around the Pacific."[cl] This new fascination with science and culture extended well into other Western countries, and it has been recorded that in Europe, youths were only admitted to a popular sideshow that featured anatomical waxworks if they claimed they were medical students.[cli] In the case of Al Tomaini "Giant Boy", mythical origins about giants were replaced by a modern "Lesson in Glands". Science allowed a reimagining of the body—that of sameness and homogeneity,[clii] and in the case of "Julee—Juliane" (the Hermaphrodite), science replaced myth by transforming him/her into an extraordinary being and transcending his/her origins beyond myths such as the one told by the Greek poet, Aristophane—that man was originally created as both man and women in one body. In this space, taboos could be transcended and psychological constructions of identity were based solely on the lack of abnormality. Through science, the spectator no longer questioned 'authenticity', they were told what it is. They were shown that even the most disabled bodies are useful, that money is to be made, items must be purchased, education is valued, and most importantly, normality is revered. The turmoil of the 19th and early 20th century created a perfect environment for valorizing one's own self worth. During this period, the freak show or human display of 'otherness' was a vital form of American entertainment, and the spectator could leave without ever realizing they were taking part in a greater dialogue.Bibliography

Adams, Rachel. Sideshow U.S.A.:Freaks and the American Cultural Imagination. Alexander, Edward P. The museum in America: innovators and pioneers. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 1997. Appel, Toby A. The Cuvier-Geoffroy debate: French biology in the decades before Darwin. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. Ashby, LeRoy. With Amusement for All: A History of American Popular Culture Since 1830. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2006. Bailly, Christian. Automata: The Golden Age, 1848-1914. Robert Hale Limited, 2003. Barnum, P.T. The life of Barnum : the world-renowed showman : his early life and struggles; bold ventures and brilliant successes; wonderful career in which he made and lost fortunes; captivated kings, queens, nobility and millions of people; his genius, wit, eloquence, public benefactor, life as a citizen, etc., etc. : a remarkable story, abounding in facinating incidents, thrilling episodes, and marvelous achievements / written by himself ; to which is added The art of money getting, or Golden rules for making money. London, Ontario, McDermid & Logan, [1891?] Baynton, D.C. "Disability & the Justification of Enequality in American History" From New Disability History. P. Longmore & L Umansky (eds), 2001. Bedini, Silvio A. The Role of Automata in the History of Technology. Technology and Culture 5:1 (Winter 1964):24-42 Bell, Whitfield J. "The Cabinet of the American Philosophical Society" p. 1-48. In Whitehill, Walter Muir. Cabinet of curiosities: five episodes in the Revolution of American museums. Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia [1967] Blumin, Stuart M. The Emergence of the Middle Class: Social Experience in the American City, 1760-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980. Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. Bombanci, Nancy. Freaks in late modernist American culture : Nathanael West, Djuna Barnes, Tod Browning, and Carson McCullers. New York: Peter Lang, 2006. Bondeson, Jan. The Two-headed Boy, and Other Medical Marvels. Bottigheimer, B. Fairy Tales and Society. Brown, Henry T. Five Hundred and Seven Mechanical Movements: Embracing All Those Which Are Most Important in Dynamics, Hydraulics, Hydrostatics, Pseumatics, Steam en Astragal Press, 1995. Brown, Richard D. Modernization: The Transformation of American Life 1600-1865. New York: Hill and Wang, 1976. Brunvand, Jan Harold. The Study of American Folklore: An Introduction. New York, Norton & Company, 1968. Cassuto, Leonard, ""What an Object He Would Have Made of Me!"" In Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York 1996) Cassuto, Leonard. The Inhuman Race: The Racial Grotesque in American Literature and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. Castle, Terry. The Female Thermometer: Eighteenth-Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny (Ideologies of Desire). Oxford University Press, 1995. Chambers, Robert. The book of days, a miscellany of popular antiquities in connection with the calendar, including anecdote, biography, & history, curiosities of literature and oddities of human life and character. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. 1863. Chapuis, Alfred. Automata: A Historical and Technological Study. Neuchatel, Editions du Griffon, 1958. Click, Partricia C. The Spirit of the Times: Amusements in Nineteenth-Century Balitimore, Norfolk, and Richmond. Charlotesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989. Cocks, Catherine. Doing the Town: The Rise of Urban Tourism in the United States, 1850-1915. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. Cohen, Bernard. The Eighteenth-Century Origins of the Concept of Scientific Revolution. Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 37, No. 2. (Apr. - Jun., 1976), pp. 257-288. Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome, editor. Monster theory: Reading culture. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 1996. Conn, Steven. Museums and American intellectual life, 1876-1926. Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 1998. Crawford, Julie. Marvelous Protestantism: Monstrous Births in Post-Reformation England. Daston, Lorraine. Wonders and the order of nature. New York : Zone Books ; Cambridge, Mass. : Distributed by MIT Press, 1998. Daston, Lorraine and Kathryn Park "Unnatural Conceptions" Dennett, Andrea Stulman. Weird and wonderful: the dime museum in America. New York: New York University Press, 1997. Dundes, Alan. "Seeing is Believing" In The Nacirema: Readings on American Culture. Spradley, Japes p. and Michael A. Rynkiewich Eds. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1975. Dunlap's American Daily Advertiser, published as Dunlap's American Daily Advertiser. January 28, 1791. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 4. Dunlop, M.H. "Curiosities Too Numerous to Mention: Early Regionalism and Cincinnati's Western Museum. American Quarterly Vol. 36. No. 4. (Autumn, 1984):524-548. Evans, R. J. W. and Alexander Marr. Curiosity and wonder from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Ashgate Publishing, 2006. Ewers, John C. "William Clark's Indian Museum in St. Louis 1816-1838." p. 49-72. In Whitehill, Walter Muir. Cabinet of curiosities: five episodes in the Revolution of American museums. Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia [1967]. Findlen, Paula. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Studies on the History of Society and Culture , No 20). University of California Press, 1996. Freedberg, David. The Eye of the Lynx: Galileo, His Friends, and Beginnings of Modern Natural History. Fryer, David M. and John C. Marshall. "The Motives of Jacques Vaucansan" Technology and Culture 20 (Jan1979):257-69. Gaines, Jane M. "Everyday Strangeness: Robert Ripley's International Oddities as Documentary Attractions. New Literary History 33.4 (2002): 781-801. Garland, Robert. The eye of the beholder: Deformity and disability in the Graeco-Roman world. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1995. Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. "Making Freaks: Visual Rhetorics and the Spectacle of Julia Pastrana" in Cohen and Weiss. Thinking the Limits of the Body. SUNY Press, 2003. Greenhalgh, Paul. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World's Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988. Hankins, Thomas L. Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995. Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Free Association Books, 1996. Helman, Cecil. The body of Frankenstein's monster: Essays in myth and medicine. New York: Norton, 1992. Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991): 344-365. Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution: Europe 1789–1848, Peter Smith Pub. Inc., 1999. Hoffmann, Kathryn A. "Of Monkey Girls and a Hog-Faced Gentlewoman: Marvel in Fairy Tales, Fairgrounds, and Cabinets of Curiosities" Hogarth, William. Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism, A Medley. 1762. Impey, Oliver and Arthur MacGregor. The Origins of museums : the cabinet of curiosities in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Europe. Oxford [Oxfordshire] : Clarendon Press ; New York : Oxford University, 1985. Kampf, Klaus. Teratologie als Vorstufe einer Entwicklungsgeschichte: A. W. Otto (1786-1845) und sein "Museum monstrorum" Breslau 1841. Koln: Forschungsstelle des Instituts fur Geschichte der Medizin der Universitat zu Koln; Feuchtwangen: Alleinvertrieb, C.-E. Kohlhauer, 1987. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. Destination Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. Knoppers, Laura Lunger and Joan Landes (eds.). Monstrous Bodies/Political Monstrosities in Early Modern Europe. Nickles, Thomas. Philosophy of Science and History of Science Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 10, Constructing Knowledge in the History of Science. (1995), pp. 138-163. Larkin, Jack. The Reshaping of Everyday Life 1790-1840. New York: Harper & Row, 1988. Larson, Erik. The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. Leroi, Armand Marie. Mutants: On Genetic Variety and the Human Body. New York: Viking, 2003. Lindfors, Bernth. Ed. Africans on stage: studies in ethnological show business. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; Cape Town : David Philip, 1999. Lindman, Janet Moore. Ed. A Centre of Wonders:The Body in Early America. Michele Lise Tarter (Editor). Lorraine Daston and Fernando Vidal. The moral authority of nature. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2004. MacCannell, Dean. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Schocken, 1976. Marvin, Dwight Edwards. Curiosities in proverbs. New York, London, G.P. Putman's sons, 1916. Mauries, Patrick. Cabinets of curiosities. London ; New York : Thames & Hudson, 2002. "Museums and Their Purposes" The Museum News 1:8 (March 1906): 110. New York Daily Gazette. Published as the New-York Daily Gazette. January 4, 1790. p.3. Orosz, Joel J. Curators and culture : the museum movement in America, 1740-1870. Tuscaloosa : University of Alabama Press, 1990. Par'e, Ambroise, 1510-1590. On monsters and marvels. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983. Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser. 19 August 1789. Issue 3292. Page 3. Pickover, Clifford A. The Girl Who Gave Birth to Rabbits: A True Medical Mystery. Poignant, Roslyn, Professional Savages: Captive Lives and Western Spectacle, (London 2004) Price, Derek J. De Solla. Automata and the Origins of Mechanism and Mechanistic Philosophy. Technology and Culture 5:1 (Winter 1964):9-23 Purcell, Rosamond. Special cases: Natural anomalies and historical monsters. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1997. Riskin, Jessica. "The Defecating Duck, Or, The Ambiguous Origins of Artificial Life" Critical Inquiry 29:4 (Summer 2003): 599-633. Rydell, Robert. All the World's a Fair : Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. Rydell, Robert. "Darkest Africa": African Shows at America's World's Fairs, 1893-1940. In Africans on Stage. Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1999. Sears, John. Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the 19th Century. Oxford, 1989. Sellers, Charles Coleman. Mr. Peale's Museum : Charles Willson Peale and the first popular museum of natural science and art. New York : Norton, 1980. Seltzer, Mark. Bodies and Machines. Routledge, 1992. Shapin, Steven and Simon Schaffer. Leviathan and the air-pump : Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life : including a translation of Thomas Hobbes, Dialogus physicus de natura aeris Siraisi, Nancy G. The clock and the mirror: Girolamo Cardano and Renaissance medicine. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997. Standage, Tom. The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine. Berkley Trade, 2003 Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993. Stewart, Susan. Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979. Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. Todd, Dennis. Imagining monsters: Miscreations of the self in eighteenth-century England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 1. (Jan.1, 1769-Jan.1, 1771), pp. v-xii. Tucker, Holly. Pregnant fictions: childbirth and the fairy tale in early-modern France. Detroit : Wayne State University Press, c2003. Tucker, Louis Leonard. "Ohio Show-Shop" The Western Museum of Cincinnati 1820-1867. In Cabinet of curiosities: five episodes in the Revolution of American museums. Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia [1967]. Uebel, Michael. Ecstatic Transformation: On the Uses of Alterity in the Middle Ages. Wallace, Irving. The fabulous showman; the life and times of P. T. Barnum. New York, Knopf, 1959. Warner, Marina. Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors, and Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Warner, Marina. Fantastic Metamorphoses, Other Worlds: Ways of Telling the Self. Weschler, Lawrence. Mr. Wilson's cabinet of wonder. New York: Pantheon Books, c1995. Whitehill, Walter Muir. Cabinet of curiosities: five episodes in the Revolution of American museums. Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia [1967] Wilson, Eric G. The Melancholy Android: On the Psychology of Sacred Machines Wilson, Dudley. Signs and portents : Monstrous births from the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment. London; New York : Routledge, 1993.Notes

[cxxii] Greenhalgh, Paul. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World's Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988, 102. [cxxiii] See Cocks, Catherine. Doing the Town: The Rise of Urban Tourism in the United States, 1850-1915. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001, 191-193. [cxxiv] Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991), 356. [cxxv] Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991), p.345. [cxxvi] Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991), 345. [cxxvii] Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991), 363. [cxxviii] Siegel, Fred, TDR. 35 (Winter 1991), 108. [cxxix] Cassuto, Leonard, ""What an Object He Would Have Made of Me!"" In Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York 1996), 245. [cxxx] Disher, M. Willson, Fairs, Circuses and Music Halls. (London 1942). [cxxxi] Thomson, Rosemarie Garland. Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York, 1996, 2. [cxxxii] Siegel, Fred, TDR. 35 (Winter 1991), 113; Taylor 2002: 244. [cxxxiii] Siegel, Fred, TDR. 35 (Winter 1991), 114. [cxxxiv] Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Odditites for Amusement and Profit. Chicago, 1988, 1, 280-281. [cxxxv] Siegel, Fred, TDR. 35 (Winter 1991), 114. [cxxxvi] Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991), 345. [cxxxvii] Martin-Barbero, J., Communication, Culture, and Hegemony, (London,1987), 19. [cxxxviii] Thomson, Rosemarie Garland. Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York, 1996, 2-3. [cxxxix] Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. London 1993, 108. [cxl] Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. London 1993, 109. [cxli] Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991), 357-358. [cxlii] Hinsley, Curtis M., "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. (Washington 1991), 358. [cxliii] Fiedler, Leslie. Freaks: Myths & Images of the Secret Self. New York, 1978, 282-283. [cxliv] Pit-show is defined as "An exhibition of freaks displayed in a "pit" built of boards or canvas, around the top of which is a walk for the customers." (Maurer 1931:334) [cxlv] "The word is reputed to have originated with a man named Wagner of Charleston, W. Virginia, whose hideous snake-eating act made him famous." (Maurer 1931:331) [cxlvi] Apter, Andrew, "The Pan-African Nation: Oil-Money and the Spectacle of Culture in Nigeria" Public Culture 8 (1996): 441-466. [cxlvii] Mannix, Daniel P., Freaks: We Who Are Not As Others. San Francisco, 1990. 28); Mannix, Daniel P., Freaks: We Who Are Not As Others. San Francisco, 1990, 87; Adams, Rachel, Sideshow U.S.A.:Freaks and the American Cultural Imagination (Chicago 2001), 222; Taylor, James, "Shocked and Amazed" On and Off the Midway, 6 (Baltimore 2001),1; Taylor, James and Kathleen Kotcher, "Shocked and Amazed" On & Off the Midway. (Connecticut 2002), 49; Adams, Rachel, Sideshow U.S.A.:Freaks and the American Cultural Imagination (Chicago 2001), 30. These individuals, although from different ethnic backgrounds, experienced their own cultural citizenship. Toby Miller suggests that cultural citizenship should take into consideration political, economic, and cultural concerns, all of which these commodified individuals partake in. These individuals, although from different ethnic backgrounds, experienced their own cultural citizenship. Toby Miller suggests that cultural citizenship should take into consideration political, economic, and cultural concerns, all of which these commodified individuals partake in. See Taylor, James, "Shocked and Amazed" On and Off the Midway, 6 (Baltimore 2001). [cxlviii] Sociologist Bell Hooks, for example, studied the exploitation of the black female body through the 'commodification of otherness', and Joseba Gabilando also examines 'commodification of otherness' in the construction of Basque identity and Spanish culture. See Hooks, Bell, Black Looks: Race and Representation, (Cambridge 1992); Gabilondo, Joseba, Archaeology of Global Desire: New Hollywood, Spectacle Hegemony, and the Commodification of Otherness, Forthcoming; Gabilondo, Joseba, Empire and Terror: Nationalism/Postnationalism In the New Millennium. (Nevada 2005). [cxlix] Quigley, Christine, "Mummy Dearest" in Taylor, James and Kathleen Kotcher. "Shocked and Amazed" On & Off the Midway, (Connecticut 2002), 205-211. [cl] Vaughan, Christopher A, "Ogling Igorots: The Politics and Commerce of Exhibiting Cultural Otherness, 1898-1913." In Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. Ed. Rosemarie Garland Thomson. New York 1996, 231. [cli] Disher, M. Willson, Fairs, Circuses and Music Halls (London 1942), 36. [clii] Thomson, Rosemarie Garland. Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body . New York, 1996, 12.Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

Adult Reading and Writing Tutors

IB Language A: Language and Literature Tutors

Acoustical Engineering Tutors

Fluid Dynamics Tutors

UK A Level Turkish Tutors

NBDHE - National Board Dental Hygiene Examination Tutors

Canadian History Tutors

Writing Tutors

Biology Tutors

French Tutors

CCNA Cyber Ops - Cisco Certified Network Associate-Cyber Ops Tutors

Engineering Tutors

Italian Renaissance Tutors

AP German Language and Culture Tutors

Australian Studies Tutors

Application Design Tutors

Modernism Tutors

Algebra 3/4 Tutors

Child Development Tutors

Editing Tutors

Popular Test Prep

SAT Subject Test in United States History Test Prep

CSET - California Subject Examinations for Teachers Test Prep

Oregon Bar Exam Courses & Classes

SAT Courses & Classes

CTRS - A Certified Therapeutic Recreation Specialist Test Prep

USMLE Courses & Classes

SIE Test Prep

Certified Ethical Hacker Test Prep

Series 65 Courses & Classes

CLEP Precalculus Test Prep