Catherine Wister Miles - Mother - Wife - Business Woman - Patriot

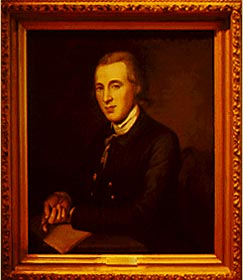

"To cobble" is a perfect description of efforts to piece together the life of a remarkable woman of the 18th Century. If she was not featured in a photograph or portrait, we can still find the life of Catherine Wister Miles to be quite remarkable - the bearer of children, the supporter of her husband, an educator, a sewer, a cook, water bearer, nurse maid, wood bearer, and mistress of the house. But to our advantage, there is a portrait. And as you stare into her eyes there is a connection with this woman whose portrait has adorned the houses of generations of her progeny. We admired her. We may have commented upon her appearance. But up to this time never fully considered the woman. Having the portrait in front of us we are afforded the opportunity of not only speculating about the life of one human being, but also to come upon an informed hypothesis, supported by fact, as to as to who the artist was. I have intensely studied her portrait for over thirty years. In analyzing its dynamic features, I have come to consider the woman, Catherine Wister Miles, and developed an informed hypothesis of who completed the portrait. For generations the portrait of Catherine Wister Miles has been in the homes of the Miles/McCann family. There is still much to be written about the courage of women in colonial America. Regrettably, however, throughout American history our focus, more than likely, turns to the courage exhibited by the men. With women there is a more romantic remembrance as opposed to a remembrance of human beings faced with great adversity. In an effort to give a complete remembrance of courage exhibited in the face of great adversity, it is important to include women as a group to be admired. Their role day after day, night after night is equal to those man- women who courageously set out to explore, to battle, to risk life and limb, and to create a new society for the United States. This article brings to light a human being – in this case a woman – who was an equal partner, with her husband, in contributing to the success of the family and this nation. She has not been featured in history books. Nor did she make the "cut" to be featured in Cokie Roberts' excellent book Founding Mothers. However, unlike so many of her fellow courageous women of the colonial era, there is a portrait of this "Founding Mother". And on closer examination, one is struck by the intensity of her spirit. At the same time, as the only 18th Century American woman portrayed with eye glasses (in her era known as sliders), the aura is one of being a learned and gentle human being. Catherine Wister Miles was the mother of 15 children. For women in the 21st century the notion of giving birth to 15 children, even with the most advanced medical technology, is a frightening thought. How brave Catherine must have been, for, in giving birth to each child, she literally put her life in jeopardy. But, how much she must have loved her children. From the time of her birth January 2, 1742 to her death on October 24, 1797, the majority of her life would be in the preparation for, giving birth to, and nurturing of children[1] By the time she had turned 19 years of age in 1761, the French and Indian War was ending and her husband to be, Samuel Miles had returned to Philadelphia as a hero. He had advanced from the lowly rank of private and was now a captain in His Majesty's armed forces. You can imagine how he appeared in his full British uniform regalia – red and gold, and beaming with pride. And no doubt she was awe struck. And she fell in love. But, the marriage between Samuel Miles and Catherine Wister was quite controversial. He was a Baptist. She was a Quaker. Interestingly, Samuel speaks only once of his wife in his writings when, in his autobiography, he refers to their marriage"On the 16th of February, 1761, I married and settled in Philadelphia, and after I became reconciled with my wife's father ..."[2]But I hope there was more to this than Samuel Miles let on. Personal pain of human relationships obviously did not faze him, or so it seems.[3] Without going into the psychological elements of how power enhances a human, and how it attracts others, Samuel Miles, as a result of his military service, had connections. The wise business people of the Quaker community recognized that. So, Samuel did his best by providing for his family. From the time Samuel and Catherine Miles were married on February 16, 1761, procreation figured prominently in her life. Catherine gave birth to 15 children (with her age noted after the year of birth) beginning in 1762/20; 1763/21; 1764/22; 1767/25; 1768/26; 1770/28; 1771/29; 1772/30; 1774/32; 1775/33; 1776 /34; 1778/36; 1780/38; 1783/41; 1785/43. The 21st Century risks in giving birth pale in comparison to what Catherine experienced in the 18th Century. But for women, regardless of the era, it must be a dichotomy of emotion! Six of Catherine and Samuel Miles' children would die very young - 1764, 1765, 1767, 1771, and 1785. Then one month before Catherine's death (October 1797), her son, Captain James Miles, died September 1797. Were their deaths a result of yellow fever in Philadelphia? Catherine died in 1797 at age 55. In doing the math, 36 years or almost 65% of her life was spent in preparing for the birth, the deaths, and the raising of children. And the other 35% - she spent preparing to be a good human being (the first 19 years in the Quaker tradition; and the remainder, which were the formative political years for her husband, supporting his endeavors). And all of this done for love! At age 19, she risked the permanent animosity of her Quaker family by marrying outside the faith.[4] But, by all accounts, Catherine Wister had strictly adhered to the Quaker faith and also became quite learned in her father's (John Wister) business. [5] She practiced what today's accountants would call "due diligence" in maintaining the books for her father's and husband's business. And there would be painstaking care to ensure the accuracy of accounts receivable and accounts payable. But to relax during the day, "due diligence" also required moments of romantic daydreaming. On the back covers of the ledgers she affectionately, time and time again, (as if enjoying her new marital status) would, in the best cursive writing, sign her name. Samuel and Catherine did not engage in the prolific letter exchanges as John and Abigail Adams. It was with Samuel's Baptist zeal, and Catherine's quiet Quaker steadfastness, they set out as husband and wife to literally change the world, each in their own way. This being the case, the family had money to maintain two homes; one in Philadelphia and one in Spring Mill (Pennsylvania's Montgomery County). How brief it must have seemed, between 1762 and 1774, when the two of them were together. Amidst it all, though, there would be time for fun![6] Twelve years and eight children later, in 1774, Samuel cast his lot with those who were seeking independence from Great Britain. And how would that impact his family, particularly his peace loving Quaker family relatives; his father-in-law; his brothers-in-law and their families? Fortunately, John Wister's family was immune from the animosity exhibited toward other Quakers who remained neutral in their feelings about the Revolutionary War. It was simple; the Quakers were against any type of war, period. But even with their neutrality, there would be many Quakers imprisoned. But remarkably, the John Wister home, on the outskirts of Philadelphia, served as a refuge for both the British and American Army officers. Catherine, on the other hand, followed the Apostle Paul's admonition, from his writings to the Ephesians, "women obey your husbands." Being of Quaker stock meant being committed to your family. Samuel Miles, who had been appointed as a Colonel by the Continental Congress, found himself going hither and yon to make regions safe for the American independence movement. First to Lewes, Delaware. Then to New Jersey. Then to New York City. By August, 1776 Samuel and his Pennsylvania riflemen found themselves in Brooklyn, New York attempting to avoid a pitched battle against the German Hessians. But the avoidance of the Hessians was for naught as his rifle regiment was discovered and a battle ensued. There were many casualties. Colonel Miles was taken prisoner, and would languish in New York until his parole in December, 1777. He was ultimately exchanged for British Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell (For more information see Brooklyn College Professor Edwin Burrows book Forgotten Patriots). It was during Samuel's time as a prisoner of war that Catherine Miles was busy keeping her family together. In the one and only letter preserved, on December 15, 1776 note she wrote to David Rittenhouse (noted astronomer and later first director of the United States Mint of the Currency). The letter was written from the safety of her second home in Spring Mill (one mile north of the Wister home in Germantown). Spring Mill December 15, 1776 "Sir - This server being informed that a number of dwelling houses in Philadelphia are taken possession of for the use of the soldiery and having a new house in 2nd St near to Mr. Hillegas which has not yet been occupied by any person I beg you would you use your influence to prevent the same being made use of for the Army as it may he easily supposed that in such case it would be liable too much injury. Colonel Miles being from home has taken the liberty to address myself to you with the hope will not be taken amiss. I am your friend and humble servant Catherine Miles

(Courtesy American Philosophical Society)

Her house was in jeopardy of destruction by marauding British soldiers. Her husband was a prisoner of war. There were children to care for. (The education of the Miles' children is mentioned in a September 3, 1783 letter from Andrew Brown to Jaspar Yeates.[7] ) But all was not lost. A Colonel in the Continental Army was given privileges only afforded those who were "gentlemen". In correspondence from General William Howe, Colonel Miles was granted a two-week parole provided, under the strictest of regulations, he did nothing to further the patriot cause. Colonel Samuel Miles was under house arrest.[8] But in December, 1777 he made good use of time as he was reunited with Catherine at their Spring Mill home. (John Wister Miles was born on September 9, 1778 The John Miles branch of the family would lead to me; hence John's birth takes on greater significance. His Majesty's Government of King George III is to be thanked for its benevolence) On April 30, 1778 he returned to his wife and would be with her for the next 19 years. Whether or not the house was taken over the by the British is not known. We do know their neighbor's home – the home of Michael Hillegas – was used as a British hospital.[9] It is known that upon his release, and upon Philadelphia being rid of the British menace, the Miles family set out to resume their lives together. Samuel as deputy quartermaster under Timothy Pickering; she as wife and mother. Three more children would be born after 1778. With the war over in 1781, the new American nation found itself changing and the cultural climate was ripe for change. Thankfully for historians, it became a time for vanity. In 1802 Samuel Miles would have a portrait completed by Gilbert Stuart. And that is documented. (now in storage at Washington's Corcoran Gallery of Art) But Catherine's portrait? No account. No record. But all indications point to the portrait being completed by Gilbert Stuart. In 1796, her brother Daniel, now living in Germantown in the family home later to be known as "Grumblethorpe", was in close proximity to the artist's studio. Beginning in 1793 portrait artist Gilbert Stuart impressed the Philadelphia elite with his portraits. Before he left Philadelphia in 1803, he painted the portrait of Samuel Miles, which is now housed in the Washington Corcoran Gallery of Art. But Catherine Wister Miles? Before her death in 1797, she sat for a portrait artist. And all the evidence significantly points to Gilbert Stuart having completed the portrait And in the studio adjacent to her late father's home she and her husband Samuel would sit and have their images portrayed by the master of American portraiture. [10] A mother. Bringing 15 children into the world. Witnessing the death of children. Revolution. Fleeing from the enemy. Maintaining a business. It's no wonder in the 1796 portrait of Catherine Wister Miles she looks much older than 54 years old.

Catherine Wister Miles

But Gilbert Stuart's attitude in painting the portraits of women was far different than in painting the portraits of men. Wrote Frank Mather, "To the men he gave what the American man wanted, a most resolute and resemblant face-painting,"[11] And the women? Towards the American woman Gilbert Stuart's attitude was that of all perceptive foreigners. She was a marvel, a puzzle, and a delight. She was irresistibly herself independent and unconditioned existence, in a sense that the American man busied with nation making could not be. [12] And in all Gilbert Stuart's works, there is Catherine Wister Miles. And in her, one can truly agree with Mather's statement Stuart is the greatest painter of women's character stands, and we gain the further point that when Stuart painted women the usually clear line between fine portraiture and consummate face painting tends to disappear.[13] In his essay "Face Painter and Feminist" Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. would go on to write about Stuart's portraiture of women as his (Stuart's) having "read her, confessed her, and most gallantly celebrated her, with the result that the mothers and daughters of the early Republic are about twice as alive as the fathers and sons."[14]It was Gilbert Stuart who "varied his response to the subject, the evocation of inner being, often in the form of an expression of either momentary or steadied –gaze (emphasis added) interaction with the viewer, was generally characteristic of his work"[15] There is uncertainty as to the cause of death of Catherine Wister Miles. Yellow fever? We do know she suffered from Waardenburg's disease which the portrait shows (drooping right eye lid and, in the infrared images of the portrait, each eye is a different color). Her death on October 24th 1797 was noted in the Philadelphia Gazette and Universal Advertiser.[16]On the 24th of this month at Cheltenham Catherine Miles the wife of Colonel Samuel Miles. Of this excellent woman it may be truly said that she fulfilled all the duties of the wife, mother, mistress, and friend and as one that was to give an account your after of her conduct. She was beloved in life and died lamented by all who knew her.There could be no more fitting epitaph to a woman of the late 18th century than what was offered in the Philadelphia Gazette and Universal Advertiser. And in her portrait the eyes gaze upon us sternly, but with the kindness - to women and men who view her – a kindness that seems to say "with a humble spirit, embrace life!" She is buried next to her husband in Philadelphia's Mount Moriah Cemetery located in the city's second council district. I liken her portrait to the Mona Lisa because it is so true to life. It was basic. It was profound. It was gentle. And it was unique because Catherine Wister Miles is the only woman in the 18th Century America to be portrayed with spectacles. She was not vain. To some it may be a bit presumptuous to compare the portrait of Catherine Wister Miles to the Mona Lisa. But after reading Donald Sassoon's book Leonardo and the Mona Lisa Story, it is equally true for Catherine Miles what he wrote about the Mona Lisa. And in the quote we could just as easily substitute "Gilbert Stuart" for Leonardo. Donald Sisson wrote

Leonardo left behind thousands of preparatory drawings and detailed notes about all aspects of his life, yet there is not a single preliminary sketch of the Mona Lisa and not a mention of it in his notebooks. This uncertainty contributes to the mystery surrounding the Mona Lisa. When the sitter is a lady of some importance identification is simple. Contracts are exchanged and records are kept. Those who commission the painting get it and keep it. Yet despite the uncertainty about the woman portrayed there has never been doubt that Leonardo painted the portrait [17]While some in the artistic community may doubt that Gilbert Stuart painted the portrait of Catherine Wister Miles, others, who have examined the portrait and the research, say there can be no doubt as to its artist, and the subject.[18] Catherine Wister Miles. Humble in life; forgotten in death – until now.

Footnotes

[1] (I would like to believe Samuel Miles was also caring for his wife and children. Certainly the loss of his mother when he was 10 years of age had an impact on his life.)

[2] "Auto-Biographical Sketch of Col. Samuel Miles," The American Historical Record (Vol 2) (14) 1873. Miles, The American Historical Record, 52.

[3] For a full accounting of the life of Catherine Miles' husband, Colonel Samuel Miles, please see Milton Rubicam, "The Wistar-Wister Family: A Pennsylvania Family's Contribution Toward American Cultural Development," Pennsylvania History 20 (April 1953), 142-164.

Catharine Wister, John's only daughter, had a romance that was nearly nipped in the bud. She fell in love with a young soldier of Welsh origin named Samuel Miles, who had seen active service in the French and Indian War and had successfully raised himself from a private to the rank of captain in His Majesty's Service.On his return to Philadelphia Captain Miles sought to win the hand of the fair Miss Wister, but her father, apparently of the opinion that the young officer did not measure up to the financial and social standards established for his son-in-law, refused his consent. But the young couple were (sic) married on February 16, 1761, without the paternal blessing. Eventually, Mr. Wister forgave his daughter and backed his son-in-law in the wine and rum trade. He never had occasion to regret his daughter's choice, for Samuel Miles became a member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly (1772), Colonel of the Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment attached to the famous Flying Camp (1776), Auditor of Public Accounts and Deputy-Quartermaster-General for Pennsylvania (1778), Judge of the High Court of Errors and Appeals (1783), Captain of the First City Troop (1786), a famous local military organization which accepts only men of prominent families (a circumstance that must have pleased old Mr. Wister!), member of the Council of Censors (1787) and of the Common Council of Philadelphia (1788), and, finally, Mayor of Philadelphia (1790).

[4] We know the notion of "shunning" among the Amish. It must have been equally as damning among the Quakers particularly those who left the religion.

[5] "There has been much research regarding the background of Catherine's parents John and Ann Catherina Rubenkam – Wister, and brothers Daniel and William. Her father, John, was a devout Quaker. John was born in Hilsbach, Germany, near Heidelberg on November 7 1708. His second wife Ann Catherina Rubenkam, was born in Wanfred, Germany. In the colonies, her father John became an importer of wines and other goods. He became quite wealthy as a result of his endeavors. It was John who built the home, later affectionately known as Grumblethorpe, that still stands today in Germantown. He was obviously well connected in Philadelphia as is testimony by his house having one of the "earliest rods (lightning) erected by Franklin", (Page Talbott, ed., Benjamin Franklin In Search of A Better World, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005, 196.). John would spell his last name Wister while his brother Casper spelled his last name Wistar. Casper preceded John in arriving in colonial America, and there are ongoing controversies among historical experts as to the influence the brothers had in many areas, particularly in the naming of the "wisteria" or "wistaria" flowering plant.

6 The account books are part of the Winterthur Downs Joseph Downs Collection, Winterthur, Delaware

[6] Jacob Cox Parsons, ed., Extracts from the Diary of Jacob Hiltzheimer (Philadelphia: William F. Fell & Company, 1893), 20, 28. Witness these activities: 1770 March 3 Took ... later went with Samuel Miles, his wife, and my wife to Frankford (Page 20) 1774 January 29—In the afternoon went down to the wharf to see the skaters on the Delaware; afterward to John Wister's, where I drank coffee with Richard Wister, Casper Wister, Daniel Wister and wife, Benjamin Morgan and wife, Samuel -Miles and wife

[7] See "Notes and Queries – Letter of Andrew Brown to Jaspar Yeates" The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1916), 378.

[8] See the Centre County Historical Society for the reprints of correspondence between General Howe, his representatives, and Colonel Miles. More interestingly, General William Howe occupied the Germantown house of Catherine Miles' cousin David Deshler. Deshler's father married John Wister's sister Marie – and son David emigrated to America joining John Wister's business in Philadelphia. The house would be used by President Washington during the yellow fever scare in 1793.

[9] Wright, Robert E. The First Wall Street: Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, and the Birth of American Finance

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 142.

[10] Charles Francis Jenkins, Washington in Germantown (Philadelphia: William J. Campbell, 1905), 309.

[11] Frank Jewett Mather, Jr., Estimates in Art (2) "Face Painter and Feminist", in Sixteen Essays on American Painters of the Nineteenth Century, (Freeport, New York: Book for Libraries Press, 1959), 9

[15] Dorinda Evans, The Genius of Gilbert Stuart (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999), 79.

[16] Microfilm copy courtesy of The Library of Congress, Washington D.C. 577. Gazette of the United States, & Philadelphia Daily Advertiser V1190.

Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

UK A Level Environmental Studies Tutors

AP Statistics Tutors

Pre-Calculus Tutors

Insurance License Tutors

Iowa Test of Basic Skills Tutors

Kinyarwanda Tutors

Malacology Tutors

LSAT Tutors

Kinesiology Tutors

Shakespeare Tutors

Applied Philosophy Tutors

SAT Subject Test in Modern Hebrew Tutors

SSAT Tutors

Neoclassicism Tutors

Greenlandic Tutors

Chemistry Tutors

Personality Psychology Tutors

Atmospheric Chemistry Tutors

Geometry Tutors

Information Architecture Tutors