Early Virginia River Trade

By Dian McNaughtThe colony of Virginia had been in existence since May of 1607, when the first 104 brave souls ventured the high seas to come to a new land on far away shores. After a rough beginning, the colony took hold and began to flourish. The people who settled the Old Dominion, regardless of their particular religious backgrounds, brought with them an abiding faith which provided a firm foundation and supported them in their lives and in their efforts to create a new nation.

After 133 years of expansion up and down the Virginia coastline and as far inland as the fall line, the colony was bursting at the seams with a population approaching 220,000. Lands had been depleted of nutrients after almost a century and a half of planting tobacco. Tobacco was to Virginia what gold was to California. Expansion into the piedmont of Virginia was essential. Some hearty souls, mainly the Germans, Scottish and Scot-Irish had already ventured into the new "West" which now extended up the James River to Point of Forks (Columbia). These new settlers found a wilderness of wild forests filled with wild animals, wild Indians and wild legends. It was a generation later that newcomers found a fairly settled country. A foundation had been laid for a respectable and advancing society.

One of the major problems of the expansion was how to get crops to the English agents in Richmond to be transported by ship to England. The current method of transportation was to tightly pack a hogshead with tobacco, attach an axle through the center of the hogshead and roll them to market. This method of transportation resulted in damage to the packed tobacco leaves. In addition, many hands were required to handle the teams of oxen needed for the hogshead each planter had to deliver to the market. All this was accomplished during the vital spring months of the planting season, when all hands were needed to work the fields.

The early families that claimed lands along the mighty James River quickly found that with its shallows, rapids and falls, it was practically impassible using their rafts and flat boats of the time. An early Tye River Scottish tobacco planter, Parson Robert Rose, was one of the first to use the Indian dugout canoe to carry his hogsheads to the Richmond market, but found them neither large enough nor stable enough to carry much cargo. By the mid 1740's, Parson Rose, after much contemplation and trial and error, devised a method of lashing two canoes together with a sawn board platform in between which enabled him to carry up to nine hogshead at a time down the James. They were reasonably stable and especially suited to the tobacco hogshead. These double dugout canoes were later known as "tobacoo canoes" or "tobacco boats." Hogshead could now be transported downriver using the double dugout method to the market in Richmond. The platforms would then be removed and sold as cut lumber and the individual canoes would return upstream laden with needed supplies for the planters. It has been found that some homes along the Richmond waterfronts were built using these platform boards in their construction.

Regardless of all the faults of this system of navigation, it allowed for the rapid development of the whole central Piedmont and that part of the valley near the James. This too, had a great deal to do with the building up of Richmond, as Richmond was the eastern port for this trade. By 1750, the Rose type "tobacco canoes" were also traveling on all the tributaries of the James as far west as Buchanan. The "rolling roads" now worked their way to the waterways. These new river ports encouraged the building of warehouse sheds to protect tobacco hogshead and other commodities until they could be moved downriver. If these new warehouse sheds were built by a main road over which people migrated by cart or wagon, it was only a matter of time before some enterprising men bought up land and put in a ferry and a ferry house.

This method of river transportation was used for 30 years until the giant flood of 1771. In May of that year, torrential rains deluged the central Blue Ridge mountain region. For sixty hours, the James River rose continuously, as much as sixteen inches per hour. In most vicinities, the flood waters reached forty five feet above the normal level of the river. All the public tobacco warehouse sheds, located beside the river, were washed away. Property losses were disastrous. It was estimated that four to six thousand hogshead of stored tobacco had been destroyed and more than half of that spring's crop of seedlings had suffered the same fate in the fields.

The results of the flood threw the Virginia colony into impoverishment. Almost all the dugout canoes along the river were swept away in the raging flood waters. Because trees for many miles inland were depleted due to the construction of the large numbers of settlements, it was impossible to rebuild the "tobacco boats".

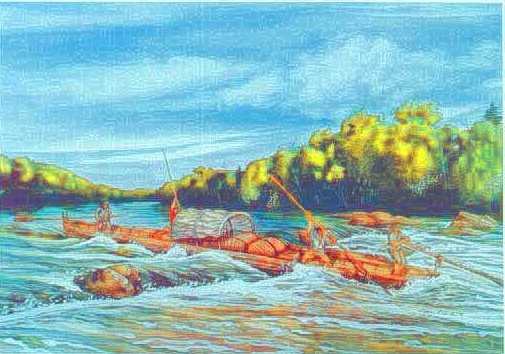

A waterman guides a batteau down the James River - early 1770s

An even better means of river transportation was initiated by Anthony and Benjamin Rucker, tobacco planters from the Pedlar's Mill area. In the early 1770's, the Rucker brothers designed a flat boat of sawn wood, pointed at both ends with a light draught, that could navigate the swift, rough water of the rapids.

These flat boats, introduced as the James River Batteau, found their inception from the French Canadian fur traders that had come into the area very early on. The traders were boat people, hence the name bateau, the French word for boat. These flat boats, enabled weight to be more evenly distributed and were more stable in swift water. They could carry up to fifteen stacked hogshead, weighing approximately 15,000 lbs., drawing only twelve to fifteen inches of water. Batteaux were from 40 to 70 feet long, and five to seven and a half feet wide, some having broad walkways laid over the gunwales for the crew to pole them along, a necessity for these batteaux to return upstream.

In 1785, George Washington appeared before the General Assembly in Virginia to further his plans for internal improvements in the Commonwealth. At his insistence, the James River Company was incorporated and he was voted the first president. The trustees were authorized and empowered to receive subscriptions to carry out the purpose of clearing the falls and construct a canal with locks. After successfully raising the necessary funds, they began their work of improving the riverbed, blasting through rock ledges, deepening channels, clearing downed trees and building a seven mile canal around the dangerous falls above Richmond, continuing up another twenty miles to Maiden's Adventure. It was the first operating canal system with locks in the United States and a vital commercial link needed to bind the Ohio and Mississippi valleys with the United States, instead of with France or Spain.

Prior to 1800, the navigation of the James River was improved by the introduction of "sluice navigation" created by building rock wing dams two thirds of the way across the river to throw an increased volume of water over the best channels at the rapids. In an 1808 report on transportation, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin stated that "the James River Sluice Navigation was one of the best in the country". By 1816, these improvements made continuous navigation for batteaux extending for 220 miles above Richmond to Buchanan.

This method of navigation also stepped up the movement of freight and the increase of trade and the encouragement of manufacturing and industry. This meant more batteaux-building yards and a greater increase in the number of trained watermen. The batteau lines were often manned by freedom loving, foot loose type of independent white men. Some of the free Negroes owned their own batteaux. Toward the later end of the era, some of the large freight lines were entirely manned by specially trained Negro hands. These men were experts in their work. It is clear from the James River Company's 1818 survey that "taking a batteau down to Richmond was still hard, dangerous work with no guarantee of success".

There were regular stop-over spots on the James where batteaumen from many batteaux would gather at dark around campfires. Meals consisted of fixings made from salt pork and corn meal, unless a farmer's stray chicken or pig crossed the batteauman's path. Stories were told of the days' trials on the mighty James. The men also made music, sang river songs and danced to pass the time.

In 1832, the old James River Company became the James River and Kanawha Company chartered to do the final link between the Ohio River and the tidewater of the James by canal and roadway. Four years later, the initial financing was completed and work on the new Kanawha Canal was started from Maiden's Adventure to Lynchburg. Eight years later, in the fall of 1840, the canal was completed to Lynchburg. It took ten more years for the canal to reach Buchanan, 196 miles upstream from Richmond and cost $8,259.000. The final leg from Buchanan to Covington, 47 miles away, was never completed.

By 1860, the forward surge of the railroads caused the James River and Kanawha Canal to gradually fade out of the picture. This expensive waterway, the dream of George Washington, had capitulated to the new, faster, railroad. "These were colorful times", Porte Crayon, the pen name for David Hunter Strother, wrote in the Virginia Illustrated magazine of 1871. "There are no boats on the river now. This cursed canal has monopolized all that trade. I perceive, too, by that infernal fizzing and squalling, that they have a railroad in the bargain. Ah me! Twenty years ago these enemies of the picturesque had no existence. The river was then crowded with boats, and its shores alive with sable boatmen, such groups! such attitudes! such costume! such character!"

Badly battered during the Civil War and almost wrecked by a severe flood in 1877, the canal's passenger packet boats and freight boats made their last trips in 1880. George W. Bagby wrote in The Old Virginia Gentleman and other Sketches, "If the James River does not behave better, hereafter, than it has done of late, the railroad will have to be suspended in mid-heaven by means of a series of stationery balloons; traveling, then may be a little wabbly, but in all events, it won't be wet." In the end, the canal was purchased by the C&O railroad (now CSX Corporation) which laid its track on the towpath. The Great Kanawha Canal Turning Basin in Richmond was filled in and used as a rail yard.

Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

Portal Tutors

IB Dance HL Tutors

Text Linguistics Tutors

Advanced Placement Tutors

Series 7 Tutors

Guitar Tutors

PMP Tutors

SAT Subject Test in World History Tutors

CSET - California Subject Examinations for Teachers Tutors

Chemistry Tutors

AP French Language and Culture Tutors

7th Grade Homework Tutors

Visual Studio Tutors

LSAT Tutors

Preschool Tutors

NNAT Tutors

Microsoft Word Tutors

2nd Grade Science Tutors

PRAXIS Tutors

CPA Tutors

Popular Test Prep

Series 3 Test Prep

PSAT Courses & Classes

LSAT Courses & Classes

Missouri Bar Exam Test Prep

Spanish Courses & Classes

CPA Courses & Classes

New Mexico Bar Exam Test Prep

CCNA Industrial - Cisco Certified Network Associate-Industrial Courses & Classes

CCNA Industrial - Cisco Certified Network Associate-Industrial Test Prep

WEST-E Test Prep