Anne Forster Berkeley: The Woman of Whitehall

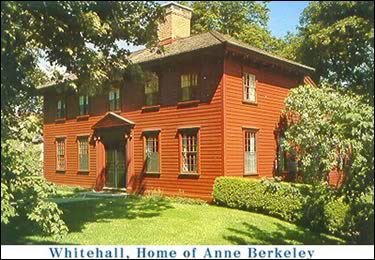

By Mary Jo Klick Like so many early American homes, Whitehall, in Middletown (formerly a part of Newport), Rhode Island, is associated with the man who lived there. Seldom is the woman of the house named or remembered. This is often true whether or not the man made any impact on the history of the nation, the town, the surrounding countryside, or the struggle for independence. The assumption usually is that the woman made no impact or that there was little in her life or personality to make her worthy of note. Whitehall is no exception. Whitehall was built in 1729 by Dean George Berkeley, philosopher and later Anglican bishop of Cloyne in County Cork, Ireland. It was home to the Berkeley family for just two years, from 1729 - 1731. The house stands today, owned and maintained by the Newport branch of the Colonial Dames of America, as a tribute to this famous man and his presence in colonial Newport. Newport, by 1730, was a city of 5,000 people. The city attracted hundreds of craftsmen and merchants whose shops lined the narrow streets leading away from the busy waterfront. Prosperous tailors, carpenters, tanners, weavers, butchers and brewers, clockmakers and stonemasons, civil officers and farmers contributed to the wealth and developing urban complexity that marked Newport in the early 18th century. Amid the bustle of this busy port, Newport citizens marked the arrival on January 23, 1729 of a ship from Virginia bringing among its passengers the highest ranking English churchman ever to visit New England. John Comer, a Baptist minister, noted in his diary: "This day Dean George Berkeley arrived here with his spouse and a young ladie in companie ...."[1]Press, 1979) 1-2, 12. It was not unusual in its time that Comer provided neither the name of the companion nor the name of the spouse of this illustrious visitor.

Even in our own time this seems still to be the case. On a tour of the house, the woman of Whitehall was mentioned only as "Berkeley's wife," never by her given name which on this occasion the docent could not recall. On another occasion the docent suggested that Mrs. Berkeley was simply a "non-entity" during her two years in Newport and so there is little interest in her. In the graveyard at Trinity Church in Newport a large stone near the grave of Nathaniel Kay, one of colonial Newport's leading citizens and a friend of the Berkeley's, marks the grave of "Lucia Berkeley, daughter (an infant) of Dean Berkeley." Again, it was common practice in the 18th century to list only the father of the deceased. So, the name of the mother who buried her infant daughter on September 5, 1731, two days before leaving Newport for Boston and the Berkeley's eventual return to England and Ireland, is missing from the tombstone. Every year, on September 5th, the Colonial Dames of America commemorate Lucia Berkeley's brief life at a grave side ceremony. Lucia's mother is strangely absent from the occasion, preserving her status as "non-entity" in a place she always remembered with great fondness.

Shortly before George Berkeley set sail for America to await a royal grant for his proposed college in Bermuda for the education of plantation owners' sons for the ministry, he married Anne Forster. She was a member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. Her mother was related to the Duke of Albemarle. Anne Forster was the eldest daughter of John Forster, Speaker of the Irish Commons (1707-9), who also had been Recorder of Dublin as well as the Chief Justice. She and her future husband had probably met during his student days in Dublin. A paternal uncle, Nicholas Forster, was a bishop who assisted at Berkeley's consecration to holy orders in 1709.[2]

On the day before sailing from England, Berkeley wrote to his friend, Thomas Prior, informing him that he had married and indicated his obvious pleasure and satisfaction with his choice: "I am married since I saw you, to Miss Forster, daughter of the late Chief Justice, whose humour and turn of mind pleases me beyond anything that I know in her whole sex...."[3] To another friend, Lord Percival, Berkeley wrote: "I chose her for the qualities of her mind and her unaffected inclination to books...."[4]

Anne Forster Berkeley was born at the dawn of the 18th century. She was educated in France and was fluent in the French language. It was most likely during her years in France that this staunch Anglican came under the influence of two French Catholic mystics, Francois de FÈnelon and Jeanne de la Motte-Guyon. Madame de Guyon was considered to be the most influential proponent of Quietism, a form of mysticism that regards the most perfect communion with God as coming only when the soul is in a state of quiet. George Berkeley's biographers report that Mrs. Berkeley was a Quietist. In her later years, she translated de Guyon's writings which she shared with fellow travelers on similar spiritual journeys.[5]

Newport, by 1730, was a city of 5,000 people. The city attracted hundreds of craftsmen and merchants whose shops lined the narrow streets leading away from the busy waterfront. Prosperous tailors, carpenters, tanners, weavers, butchers and brewers, clockmakers and stonemasons, civil officers and farmers contributed to the wealth and developing urban complexity that marked Newport in the early 18th century. Amid the bustle of this busy port, Newport citizens marked the arrival on January 23, 1729 of a ship from Virginia bringing among its passengers the highest ranking English churchman ever to visit New England. John Comer, a Baptist minister, noted in his diary: "This day Dean George Berkeley arrived here with his spouse and a young ladie in companie ...."[1]Press, 1979) 1-2, 12. It was not unusual in its time that Comer provided neither the name of the companion nor the name of the spouse of this illustrious visitor.

Even in our own time this seems still to be the case. On a tour of the house, the woman of Whitehall was mentioned only as "Berkeley's wife," never by her given name which on this occasion the docent could not recall. On another occasion the docent suggested that Mrs. Berkeley was simply a "non-entity" during her two years in Newport and so there is little interest in her. In the graveyard at Trinity Church in Newport a large stone near the grave of Nathaniel Kay, one of colonial Newport's leading citizens and a friend of the Berkeley's, marks the grave of "Lucia Berkeley, daughter (an infant) of Dean Berkeley." Again, it was common practice in the 18th century to list only the father of the deceased. So, the name of the mother who buried her infant daughter on September 5, 1731, two days before leaving Newport for Boston and the Berkeley's eventual return to England and Ireland, is missing from the tombstone. Every year, on September 5th, the Colonial Dames of America commemorate Lucia Berkeley's brief life at a grave side ceremony. Lucia's mother is strangely absent from the occasion, preserving her status as "non-entity" in a place she always remembered with great fondness.

Shortly before George Berkeley set sail for America to await a royal grant for his proposed college in Bermuda for the education of plantation owners' sons for the ministry, he married Anne Forster. She was a member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. Her mother was related to the Duke of Albemarle. Anne Forster was the eldest daughter of John Forster, Speaker of the Irish Commons (1707-9), who also had been Recorder of Dublin as well as the Chief Justice. She and her future husband had probably met during his student days in Dublin. A paternal uncle, Nicholas Forster, was a bishop who assisted at Berkeley's consecration to holy orders in 1709.[2]

On the day before sailing from England, Berkeley wrote to his friend, Thomas Prior, informing him that he had married and indicated his obvious pleasure and satisfaction with his choice: "I am married since I saw you, to Miss Forster, daughter of the late Chief Justice, whose humour and turn of mind pleases me beyond anything that I know in her whole sex...."[3] To another friend, Lord Percival, Berkeley wrote: "I chose her for the qualities of her mind and her unaffected inclination to books...."[4]

Anne Forster Berkeley was born at the dawn of the 18th century. She was educated in France and was fluent in the French language. It was most likely during her years in France that this staunch Anglican came under the influence of two French Catholic mystics, Francois de FÈnelon and Jeanne de la Motte-Guyon. Madame de Guyon was considered to be the most influential proponent of Quietism, a form of mysticism that regards the most perfect communion with God as coming only when the soul is in a state of quiet. George Berkeley's biographers report that Mrs. Berkeley was a Quietist. In her later years, she translated de Guyon's writings which she shared with fellow travelers on similar spiritual journeys.[5]

Her quiet mystical spirituality did not translate into a life of prayerful inactivity for Anne Berkeley. She and George Berkeley shared a long and happy marriage and indications are that it was very much an active partnership. Throughout their wait in America for the royal approval that never came, she encouraged and supported her husband and his dreams. Anne Berkeley collaborated with her husband on his philosophical works and wrote on her own as well. Her Maxims concerning Patriotism, republished as Miscellany under Berkeley's name, bears the inscription on the title page, "BY A LADY."[6] Besides their interest in religion philosophy, Anne and George Berkeley had a mutual love of music and art.

Anne Berkeley was no stranger to hard work. Her "inclination to books" seems not to have kept her from such physical labors as spinning and managing a large farm both at Whitehall and later in Ireland. Berkeley continues in his letter to Percival: "She goes [to America] with great cheerfulness to live a plain farmer's wife and wear stuff of her own spinning wheel."[7] A room on the second floor of Whitehall exhibits several spinning wheels of the type used by Anne Berkeley. She dressed herself and her family in homespun, a political and economic statement in opposition to London commercial interests. During their years at Cloyne, she managed their large farm as well as extensive relief works which included a small spinning industry during a time of famine in the Irish countryside. Berkeley writes: "She is become a great farmer of late. In these hard times we employ above a hundred men everyday in agriculture of one kind or another, all of which my wife directs. ... My wife finds in it a fund of health and spirits, beyond all fashionable amusements in the world."[8]

The voyage to America had been long and rough. During that voyage, Anne became pregnant. Their first child, Henry, was born at Whitehall on June 12, 1729. He was baptized in September by his father in Trinity Church.[9] In the spring of 1730, Anne Berkeley suffered a miscarriage which left her quite ill for some time. By March 1731, she was expecting again. By that time, the Berkeley's had learned that the royal grant would not be forthcoming and had begun to make plans to return to England. Their departure was delayed by the imminence of Anne's confinement. The actual birth date of Lucia is not recorded, but she lived only a few months. She was baptized in late August and was laid to rest in Trinity Churchyard less than two weeks later on September 5, 1731.[10]

Four days later, the Berkeley's left Newport. They spent 12 days in Boston before setting sail for England on September 21. Again there is no record, but it is not hard to imagine the terrible grief with which Anne Berkeley departed Whitehall and America. It is difficult enough for a mother to bury a child but even more so to leave her in a borrowed grave knowing that she will never again visit it or lay flowers there. Although they miss the opportunity to honor a courageous woman, in their annual ceremony the Colonial Dames do for Anne Berkeley what an ocean prevented her from ever doing during her lifetime.

In 1734, George Berkeley was named bishop of Cloyne in Ireland. By this time the Berkeley family had increased and their journey to Ireland included Henry and his little brother, George, born in London in September 1733. During their years at Cloyne, Anne Berkeley would bear four more children. Two of them, John and Sarah, died in infancy. A son, William, said to be the bishop's favorite, died at age sixteen. In addition to Henry and George, a daughter, Julia, lived into adulthood. [11]

The Berkeley family lived in Cloyne until 1751. Their home, the Manse, was a center for the arts. Berkeley supervised his children's education which included music and painting. An Italian music master lived in the house and instructed the children in singing and musical instruments. Anne Berkeley was a fine singer and in 1746 took up painting. In letters to Prior, Berkeley commented favorably and with his usual exuberance on her talents. In singing, she was inferior to no one in the kingdom. In painting, "she shows a most uncommon genius", he remarked concerning her portrait of him.[12]

In 1751, the bishop with his wife and daughter, Julia, left Cloyne. They settled in Oxford where Berkeley could more closely supervise George's education at Christ Church. Berkeley, much older than his wife, had been in failing health for several years. In January 1753, while spending an afternoon with Anne Berkeley reading aloud from the bible, George Berkeley died suddenly. He had made a will appointing Anne Berkeley sole executrix and guardian of their children, bequeathing to her all his worldly possessions.[13]

Her quiet mystical spirituality did not translate into a life of prayerful inactivity for Anne Berkeley. She and George Berkeley shared a long and happy marriage and indications are that it was very much an active partnership. Throughout their wait in America for the royal approval that never came, she encouraged and supported her husband and his dreams. Anne Berkeley collaborated with her husband on his philosophical works and wrote on her own as well. Her Maxims concerning Patriotism, republished as Miscellany under Berkeley's name, bears the inscription on the title page, "BY A LADY."[6] Besides their interest in religion philosophy, Anne and George Berkeley had a mutual love of music and art.

Anne Berkeley was no stranger to hard work. Her "inclination to books" seems not to have kept her from such physical labors as spinning and managing a large farm both at Whitehall and later in Ireland. Berkeley continues in his letter to Percival: "She goes [to America] with great cheerfulness to live a plain farmer's wife and wear stuff of her own spinning wheel."[7] A room on the second floor of Whitehall exhibits several spinning wheels of the type used by Anne Berkeley. She dressed herself and her family in homespun, a political and economic statement in opposition to London commercial interests. During their years at Cloyne, she managed their large farm as well as extensive relief works which included a small spinning industry during a time of famine in the Irish countryside. Berkeley writes: "She is become a great farmer of late. In these hard times we employ above a hundred men everyday in agriculture of one kind or another, all of which my wife directs. ... My wife finds in it a fund of health and spirits, beyond all fashionable amusements in the world."[8]

The voyage to America had been long and rough. During that voyage, Anne became pregnant. Their first child, Henry, was born at Whitehall on June 12, 1729. He was baptized in September by his father in Trinity Church.[9] In the spring of 1730, Anne Berkeley suffered a miscarriage which left her quite ill for some time. By March 1731, she was expecting again. By that time, the Berkeley's had learned that the royal grant would not be forthcoming and had begun to make plans to return to England. Their departure was delayed by the imminence of Anne's confinement. The actual birth date of Lucia is not recorded, but she lived only a few months. She was baptized in late August and was laid to rest in Trinity Churchyard less than two weeks later on September 5, 1731.[10]

Four days later, the Berkeley's left Newport. They spent 12 days in Boston before setting sail for England on September 21. Again there is no record, but it is not hard to imagine the terrible grief with which Anne Berkeley departed Whitehall and America. It is difficult enough for a mother to bury a child but even more so to leave her in a borrowed grave knowing that she will never again visit it or lay flowers there. Although they miss the opportunity to honor a courageous woman, in their annual ceremony the Colonial Dames do for Anne Berkeley what an ocean prevented her from ever doing during her lifetime.

In 1734, George Berkeley was named bishop of Cloyne in Ireland. By this time the Berkeley family had increased and their journey to Ireland included Henry and his little brother, George, born in London in September 1733. During their years at Cloyne, Anne Berkeley would bear four more children. Two of them, John and Sarah, died in infancy. A son, William, said to be the bishop's favorite, died at age sixteen. In addition to Henry and George, a daughter, Julia, lived into adulthood. [11]

The Berkeley family lived in Cloyne until 1751. Their home, the Manse, was a center for the arts. Berkeley supervised his children's education which included music and painting. An Italian music master lived in the house and instructed the children in singing and musical instruments. Anne Berkeley was a fine singer and in 1746 took up painting. In letters to Prior, Berkeley commented favorably and with his usual exuberance on her talents. In singing, she was inferior to no one in the kingdom. In painting, "she shows a most uncommon genius", he remarked concerning her portrait of him.[12]

In 1751, the bishop with his wife and daughter, Julia, left Cloyne. They settled in Oxford where Berkeley could more closely supervise George's education at Christ Church. Berkeley, much older than his wife, had been in failing health for several years. In January 1753, while spending an afternoon with Anne Berkeley reading aloud from the bible, George Berkeley died suddenly. He had made a will appointing Anne Berkeley sole executrix and guardian of their children, bequeathing to her all his worldly possessions.[13]

Anne Berkeley lived until 1786. During her long years of widowhood, she continued to promote the philosophical legacy of her husband. Her comments on his ideas can be found on manuscripts in the Chapman collection at Trinity College. These include her own story of the plight of the Bermuda plan in Parliament and an account of their years in Rhode Island.[14]

Throughout her long life, Anne Berkeley continued as an ardent follower of FÈnelon and de Guyon, translating passages from their works and including them in her letters to others. While living with her son, George, in London, she received a visitor from America. William Samuel Johnson was the son of Reverend Samuel Johnson whose friendship with the Berkeley's, begun in America, continued after their return to England. In subsequent letters to William Johnson who apparently shared her interest in mysticism, Anne Berkeley instructed him. In one letter she recommends that Johnson "get Laws works & Behmens & particularly get his Way to Christ. These two very fine papers Mrs. Berkeley had the pleasure of translating for Doctor Johnson "wch when he compareth with his Bible he will find to be the quintessence of the Bible — that for wch every thing was wrote & instituted — that they may be of infinite use to him is the Prayer of A-Bó"[15]

A follower also of Dr. Nathaniel Hooke, she advised Johnson: "Mrs. Berkeley presents her compliments to Doc: Johnson & sends him the Promised Manuscripts, which are Invaluable & genuine. She got them, some from Mr. Hooke, some from two of his most Intimate Friends, please to remember that NO MANUSCRIPT OF MR. HOOK'S [sic] with his Name to it must be printed, even in America.... "[16]

Anne Berkeley ended another letter to Johnson dated May 18th 1771: "I go please God in a fortnight to Canterbury to reside if I live so long for three years."[17] In a letter to his father, William Johnson provided a description of Anne Berkeley at age seventy. "She is the finest old lady I ever saw; sensible, lively, facetious and benevolent. She insinuates herself at first acquaintance into one's esteem, and begets a high opinion of her virtues. She received me very affectionately and remembered America and you in particular with great regard...." [18]

Anne Berkeley would live 15 years beyond 1771. In 1780, her son George commented that, at age 80, her powers were "as great as ever and very few persons have exceeded her in this respect."[19] She died in Langley, England, on May 27, 1786.

This paper is written as a tribute to all the unnamed and mostly forgotten women who in so many cases managed the homesteads now so carefully preserved in their husband's names. It is a tribute to all the women who transformed early America's cold, drafty houses into warm, welcoming homes — especially to Anne Forster Berkeley, the woman of Whitehall.

Anne Berkeley lived until 1786. During her long years of widowhood, she continued to promote the philosophical legacy of her husband. Her comments on his ideas can be found on manuscripts in the Chapman collection at Trinity College. These include her own story of the plight of the Bermuda plan in Parliament and an account of their years in Rhode Island.[14]

Throughout her long life, Anne Berkeley continued as an ardent follower of FÈnelon and de Guyon, translating passages from their works and including them in her letters to others. While living with her son, George, in London, she received a visitor from America. William Samuel Johnson was the son of Reverend Samuel Johnson whose friendship with the Berkeley's, begun in America, continued after their return to England. In subsequent letters to William Johnson who apparently shared her interest in mysticism, Anne Berkeley instructed him. In one letter she recommends that Johnson "get Laws works & Behmens & particularly get his Way to Christ. These two very fine papers Mrs. Berkeley had the pleasure of translating for Doctor Johnson "wch when he compareth with his Bible he will find to be the quintessence of the Bible — that for wch every thing was wrote & instituted — that they may be of infinite use to him is the Prayer of A-Bó"[15]

A follower also of Dr. Nathaniel Hooke, she advised Johnson: "Mrs. Berkeley presents her compliments to Doc: Johnson & sends him the Promised Manuscripts, which are Invaluable & genuine. She got them, some from Mr. Hooke, some from two of his most Intimate Friends, please to remember that NO MANUSCRIPT OF MR. HOOK'S [sic] with his Name to it must be printed, even in America.... "[16]

Anne Berkeley ended another letter to Johnson dated May 18th 1771: "I go please God in a fortnight to Canterbury to reside if I live so long for three years."[17] In a letter to his father, William Johnson provided a description of Anne Berkeley at age seventy. "She is the finest old lady I ever saw; sensible, lively, facetious and benevolent. She insinuates herself at first acquaintance into one's esteem, and begets a high opinion of her virtues. She received me very affectionately and remembered America and you in particular with great regard...." [18]

Anne Berkeley would live 15 years beyond 1771. In 1780, her son George commented that, at age 80, her powers were "as great as ever and very few persons have exceeded her in this respect."[19] She died in Langley, England, on May 27, 1786.

This paper is written as a tribute to all the unnamed and mostly forgotten women who in so many cases managed the homesteads now so carefully preserved in their husband's names. It is a tribute to all the women who transformed early America's cold, drafty houses into warm, welcoming homes — especially to Anne Forster Berkeley, the woman of Whitehall.

End Notes

[1] Edwin S. Gausted, George Berkeley in America. (New Haven and London: Yale University

[2] A.A. Luce, The Life of George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne. (London: Thom Nelson & Sons, 1949) 11.

[3] George Berkeley to Thomas Prior (September 5, 1728) quoted in John Wild, George Berkeley: A Study of His Life and Philosophy. (New York: Russell & Russell, 1962) 306.

[4] George Berkeley to Lord Percival quoted in Luce 11.

[5] Luce 11.

[6] Luce 180.

[7] George Berkeley to Lord Percival quoted in Luce 11.

[8] George Berkeley (February 17, 1747) quoted in Luce 180.

[9] Luce 124.

[10] Luce 124.

[11] Luce 182.

[12] Luce 180.

[13] Luce 221.

[14] Luce iii.

[15] Anne Berkeley to William Samuel Johnson in Yale University Library Gazette, Vol. VIII, No. 1, July 1933. 29-41.

[16] Yale University Library Gazette.

[17] Yale University Library Gazette.

[18] William Samuel Johnson to Samuel Johnson in Yale University Library Gazette.

[19] Luce 11.

Works Cited

Gausted, Edwin S. George Berkeley in America. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1979 Luce, A. A. The Life of George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne. London: Thom Nelson & Sons, 1949. Wild, John. George Berkeley: A Study of His Life and Philosophy. New York: Russell & Russell, 1962. Yale University Library Gazette. Vol. VIII, No. 1, July 1933.Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

High School Political Science Tutors

CFP Tutors

CFA Tutors

Natural Language Processing Tutors

Series 55 Tutors

Gender Studies Tutors

Aerospace Engineering Tutors

Resource Management Tutors

Bass Guitar Tutors

Math 3 Tutors

iOS Development Tutors

Sign Language Tutors

Inorganic Chemistry Tutors

SBAC Tutors

HTML Tutors

Real Estate Licenses Tutors

Bar Review Tutors

Cultural Anthropology Tutors

Solid State Physics Tutors

Renewable Energy Tutors

Popular Test Prep