William Bainbridge: America's Unlucky Sea Captain

By Thomas Jewett William Bainbridge was one of the fathers of the United States Navy. He helped lay the groundwork by which the Navy would become a professional force. He is so esteemed that four ships in America’s naval service have borne his name. And, he was probably one of the most unlucky officers to ever wear the uniform. Bainbridge was born in Princeton, New Jersey on May 7, 1774 into a large family. He was well educated but opted to go to sea in the merchant service at the age of fifteen, which fit his adventurous spirit. By the age of nineteen he was in command of a trading schooner in the West Indies trade.

During this time American trading vessels were supposed to be excluded by the Navigation Laws from commerce with the British West Indies. These laws had been enacted to keep Americans out of the fray between France and Great Britain. Bainbridge, therefore, by engaging in this contraband commerce, was fair game for both countries.

Bainbridge was born in Princeton, New Jersey on May 7, 1774 into a large family. He was well educated but opted to go to sea in the merchant service at the age of fifteen, which fit his adventurous spirit. By the age of nineteen he was in command of a trading schooner in the West Indies trade.

During this time American trading vessels were supposed to be excluded by the Navigation Laws from commerce with the British West Indies. These laws had been enacted to keep Americans out of the fray between France and Great Britain. Bainbridge, therefore, by engaging in this contraband commerce, was fair game for both countries.

In 1796, while commanding the ship Hope, on its passage from Bordeaux to St. Thomas in the Caribbean, his ship was attacked by a British privateer of eight guns and thirty men. The Hope’s armament consisted of four cannon manned by nine sailors. Bainbridge forced the privateer to strike its colors. He could have taken it as a prize, but is reported to have cockily hailed the other captain and told him to “go about his business and report to his masters that if they wanted his ship they must send a greater force to take her, and a more skillful commander.”

This victory gave him quite a reputation for boldness which he added to a short time later. One of the Hope’s seamen was impressed by the British man of war Indefatigable under the command of Sir Edward Pellow. In retaliation, Bainbridge boarded the first English merchantman he encountered and took her best seaman. Though this did not help the sailor from the Hope, it did show that the British could not molest anyone under Captain Bainbridge’s care with impunity. Thus far William Bainbridge seemed anything but unlucky. His luck seem to hold into 1798. In that year he married, Susan Hyleger, the daughter of a prosperous merchant on the island of St. Bartholomew. He was also accepted into the newly reorganized United States Navy with the rank of Lieutenant and given command of the schooner Retaliation.

However, in November, 1798, sailing in the West Indies, protecting American shipping from the French, he was forced to surrender to two French frigates: Insurgent and Volunteer. He and his crew were imprisoned at the island of Guadeloupe. This inauspicious start to Bainbridge’s naval career was marked by the fact that his command was the first American ship lost in the Quasi-War with France. Bainbridge convinced the Governor of Guadeloupe to release him, his crew and his ship. He further obtained the liberty of other American prisoners. For this service he was promoted to Master Commandant and given command of the 18 gun brig Norfolk. He once again sailed against the French, this time with some success, capturing the Republican and sinking several smaller vessels.

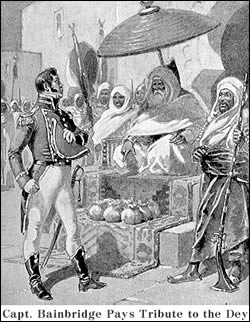

In 1800 Bainbridge was promoted to Captain and given command of the frigate George Washington. In May of that year he was tasked with delivering tribute to the Dey of Algiers. This practice, much to Bainbridge’s disgust, was to keep the Barbary corsairs from raiding American shipping. He was unlucky enough to anchor his ship within range of the Dey’s guns. Because of this he was coerced to sail under the Algerian flag to carry gifts and an ambassador to the Ottoman Porte in Constantinople, bringing humiliation to himself and his country.

Setting his humiliation aside, Bainbridge comported himself with tact and diplomacy. His efforts paved the way for the first treaty between the Ottoman Empire and the United States. He also aided in securing the release of some 400 Maltese, Venetians and Sicilians held by the Dey of Algiers for ransom.

Bainbridge was appointed to command the Essex in 1801 as part of a squadron under Commodore Richard Dale, to cruise against the North African Barbary powers. The United States, under Thomas Jefferson, had decided war was better alternative than tribute. Not much came of this cruise since U. S. naval strength was not sufficient. To help rectify this problem Bainbridge was put in charge of the construction of several new ships.

Setting his humiliation aside, Bainbridge comported himself with tact and diplomacy. His efforts paved the way for the first treaty between the Ottoman Empire and the United States. He also aided in securing the release of some 400 Maltese, Venetians and Sicilians held by the Dey of Algiers for ransom.

Bainbridge was appointed to command the Essex in 1801 as part of a squadron under Commodore Richard Dale, to cruise against the North African Barbary powers. The United States, under Thomas Jefferson, had decided war was better alternative than tribute. Not much came of this cruise since U. S. naval strength was not sufficient. To help rectify this problem Bainbridge was put in charge of the construction of several new ships.

In May, 1803 he was given command of the brand new Philadelphia which boasted 44 guns. She was the pride of a new squadron, under Commodore Preble, being fitted out to fight the Barbary corsairs. Bainbridge sailed before the rest of the fleet, and on his arrival in the Mediterranean, captured the 22 gun Moorish warship Mesh-Boha. He also recaptured the America brig Celica.

Bainbridge’s luck ran out on October 31, 1803. Off the shore of Tripoli, he rashly gave chase to a small corsair into the shallows. The Philadelphia struck an uncharted rock and became stuck. The crew attempted to tow her off the shoal by using their lifeboats, but to no avail. Much smaller Tripolitan gun-boats surrounded her. Bainbridge could not bring his cannons to bear since his ship sat at an angle, and he was forced to surrender. He and his men would remain in captivity for nineteen months suffering many privations at the hands of their captors.

The Philadelphia was refloated by the Tripolitans and taken into port to be refitted for action against the Americans. She was later burned by Stephen Decatur in a daring raid. It is said that the first suggestion for the Philadelphia’s destruction came from Bainbridge himself, in a letter smuggled to Commodore Preble. When peace was restored Bainbridge faced a court of inquiry. Although technically there was no official censure for his conduct, he always bore the stigma for the loss of his ship. After the court of inquiry, Bainbridge was not given another command, but was ordered to the navy yard in New York to supervise construction of new vessels. Due to financial difficulties, brought about by his captivity, Bainbridge requested and obtained a furlough from the Navy. He once again entered the merchant service, hoping to recoup his losses. Bainbridge continued in merchant service until 1811. While on a voyage to St. Petersburg, Russia he heard that a naval battle had taken place between England and the United States. In anticipation of a general war, he left his ship and returned to America to reclaim his commission.

He was ordered to take command of the Boston Navy Yard to prepare ships for war. On the declaration of war on June 8, 1812, Bainbridge vigorously solicited for command of a ship of the line. After several months, he was given the Constitution (“Old Ironsides”) and was also put in charge of Essex and Hornet. The newly minted commodore immediately set sail for the South Atlantic. The Constitution parted company with Hornet off San Salvador on December 26, and three days later fell in with HMS Java which sported 49 guns and 400 men. Java was on her way to the East Indies, carrying the newly appointed lieutenant-governor of Bombay. Bainbridge, for once was lucky. Java carried a very raw crew, which included few real seamen. The ship had only had one day’s gunnery drill. Bainbridge had paid great attention to honing these skills in his own crew.

The fate of Java was soon sealed. After an action of less than two hours the English ship was completely dismasted with losses of 60 killed and 101 wounded. Constitution had lost nine killed and 25 wounded. Bainbridge was among the wounded, having been struck twice. The Java, being so devastated, was blown up after the prisoners were removed. Perhaps, remembering his own times in captivity, Bainbridge treated the British magnanimously. He later received acknowledgement from the British government for his kindness. Bainbridge’s luck seems to have definitely turned. On his return to the United States Bainbridge was received as a hero and a medal commemorating his capture of Java was authorized and struck by Congress. As a reward, and to aid in his recuperation, he was ordered to take command of the Charlestown Navy Yard, where he laid the keel for Independence. After the War of 1812, Bainbridge will lead a squadron, once again, against the Barbary pirates. During the War, Algiers and Tripoli had resumed their old practices, since the United States Navy was occupied with Great Britain. A show of force was all that was needed to bring the corsairs into line.

Bainbridge spent the later part of his career in making the Navy as a professional fighting force. He established the first school for naval officers and the first board of examination for officer promotion. He also commanded several naval yards, where under his direction, development of new naval technology took place. His ill-luck returned in these years. He suffered greatly from old wounds and privations incurred during his service to his country. He will contract pneumonia in 1833 and die. How does history rate William Bainbridge? No other contemporary, American sea captain lost as many ships. His defeats, though, were balanced by spectacular victories. Victories brought about by boldness and even some suggest rashness. As long as his luck held, William Bainbridge was one of the best sea captains of his era.

Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

ARRT Tutors

Medical School Application Tutors

ACCUPLACER Elementary Algebra Tutors

IB Physics Tutors

Systems Security Tutors

Graduate-level writing Tutors

CLEP Introduction to Educational Psychology Tutors

NAPLEX Tutors

Advanced Algebra and Trigonometry Tutors

2nd Grade Writing Tutors

Anatomy & Physiology Tutors

IB Sports, Exercise and Health Science SL Tutors

Public Speaking Tutors

3rd Grade Tutors

PRAXIS Tutors

Pharmaceutical Care Tutors

Journalistic Ethics Tutors

Breton Tutors

Applied Mathematics Tutors

Spanish Tutors