Gilbert Stuart

Gilbert Stuart And the Woman Behind George Washington

The story begins when the National Park Service dedicated the museum building at Morristown National Historical Park to support the Ford Mansion or “The Headquarters” on February 22, 1937, Washington’s Birthday, and a year later, publicly opened the museum – again on February 22 - with artifacts previously owned by the Washington Association and now put on display under the auspices of the National Park Service. Mounted on the wall in the museum was a large and elaborate wall safe. Within the open doors was the gift of a Gilbert Stuart Athenaeum portrait of George Washington left to the Washington Association by an original founder, William Van Vleck Lidgerwood. The painting had been purchased by Lidgerwood at a Christie, Manson and Woods auction in England on April 23, 1887 from the estate of James T. Gibson-Craig, Esq. Mr. Gibson-Craig’s very valuable and extensive library collection was auctioned later in June that year. Upon Mr. Lidgerwood’s death, he left the painting to his niece Miss Mary V. V. Lidgerwood who presented it to the Association in 1919. Each night the doors of the safe clanked shut to protect the painting from theft. In the morning, the safe was opened and the public was once again invited to gaze at the painting. Soon after the portrait was hung in the safe, the really observant visitor began to notice something different, something changing in this popular portrait. Behind the portrait, growths or maybe even “ears,” began to appear behind General Washington. 1 It is not recorded that the more conservative members of the Washington Associated suspected a plot on the part of the Jefferson - loving FDR and his National Park Service, but, after all, the Father of his country never had rabbit’s ears when they were in charge! 2 The Park Service was also alarmed. The ears were becoming more and more apparent each day. Experts were consulted and the mystery was finally solved. Well, maybe.Gilbert Stuart’s Three Paintings of George Washington

There were three paintings that General Washington personally posed for with Gilbert Stuart. From these three came some 104 “original” paintings by Stuart. The first pose, the Vaughan portrait, painted probably in 1795, was named after the first owner, Samuel Vaughan, an American merchant living in London. Vaughan's name became associated with some seventeen versions. The second was the full length portrait known as the Lansdowne. In April 1796, Senator William Bingham, Pennsylvania, on behalf of his wife, gave the painting to William Petty, the second Earl of Shelburne and who later became the first Marques of Lansdowne. Petty was a sympathizer to the American cause of independence and spoke out in Parliament on the new country’s behalf. The painting was consigned to the honorable Rufus King, Minister to Great Britain, to present this portrait to the Marques. 3 Another of these “Lansdowne” paintings was rescued by Dollie Madison right before the British had dinner in the White House and then burned the home during the War of 1812. But the third painting is the most famous, the most copied and the one in the “wall safe.” This is a painting commissioned by Mrs. Martha Washington of her husband, the “General.” Stuart was to paint both the President and Mrs. Washington as two separate portraits. In this portrait, while Washington had the famous “badly fitting” set of false teeth and had a constrained expression about his mouth, the paintings so pleased Stuart that in the middle of the sessions he approached Washington and asked if he could keep both portraits and leave them unfinished. He did promise a replica of the paintings for Mrs. Washington. Stuart went on to finish some seventy copies of this painting owned first by the Boston “Athenaeum” gallery also known as the unfinished Washington. 4 The painting became the standard, the accepted and true likeness of Washington. Stuart, himself, called this painting his hundred-dollar bill for whenever he needed money he made a copy and always found a ready buyer. Towards the end of his life he could copy at least two of these portraits a day.

Vaughn Portrait |

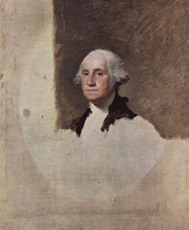

Landsdowne Portrait |

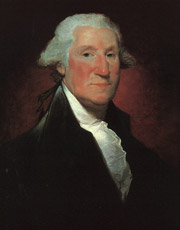

Athenaeum Washington |

The Lady Behind (Underneath) General Washington

John Wilfred Dawson in 1940 led the efforts to conserve the painting and looked for the cause of the “ears.” Dawson found that a small piece of paper was glued to the rear of the portrait that established the provenance and noted:General Washington Painted by American Stuart

I purchased this original portrait from Mr. Horace Redd No. 9 Great Newport Street for ₤ 8.00 London, June 20th, 1823. David Constable Mr. Durnfold from whom I had this picture brought a gent to look at it, who offered twenty-five guineas for it. R. Redd When the painting was fully examined, and the stretcher lifted from the canvas, hidden on the lower margin of the canvas, was a five inch long piece of paper that had written upon it in large letters, the words, “Mrs. King,” 6 There are stories of how anyone critical of Stuart’s art would see their project terminated and the unfinished canvas taken upstairs to the “garret” to later be used again. When General Knox offered a suggestion on his portrait, Stuart responded that he would make the painting the door on his pig sty. Once he delineated a handsome woman who was a great talker. When the picture was almost done, she looked at it and exclaimed: "Why, Mr. Stuart, you have painted me with my mouth open!" He replied: "Madam, your mouth is always open" and he refused to finish the picture. And another young lady stood up and went behind Stuart as he painted and gave her thoughts on how to finish the painting, and Stuart immediately, despite her tears, directed the canvas to the attic. When "a gentleman of estimable character and no small consequence in his own eyes" objected that Stuart's portrait of the rich but homely widow he had married did not make her beautiful, the artist cried: "What damned business is this of a portrait painter! You bring him a potato and expect he will paint a peach." 7 With a supply of unfinished paintings in the attic, as Stuart needed some cash, the slightly used canvas was brought down, turned around and a new hundred dollar bill painting begun. These “ears” were really shoulders! Dawson upon his examination felt that the painting was done of this Mrs. King between 1803 and 1806 while Stuart was either in Washington or on his way to Boston. As the under painting was not thoroughly dry before the Washington painting was added, this caused the cracking and in some cases the spreading of the paint, Dawson felt then, that the Washington portrait was added during the same period. An x-ray of the painting revealed the likeness of a woman, holding a large cross on her lap. This x-ray was shown to the public in an article in the Newark Evening News revisiting the discovery on February 22, 1962, with the title The Woman Behind Washington. 8Portraits of Mr. and Mrs. King By John Trumbull

In 1800, another famous painter of the era was commissioned to paint Rufus King and his wife, Mary Alsop King. This painter was Colonel John Trumbull. His male subject, Rufus King, played a prominent part in the politics of the day. Mr. King was born in Scarboro, Maine (then a district of Massachusetts), March 24, 1755; attended Dummer Academy, Byfield, Mass., and graduated from Harvard College in 1777; served in the Revolutionary War; studied law; admitted to the bar and commenced practice in Newburyport in 1780; delegate to the Massachusetts General Court 1783-1785; Member of the Continental Congress from Massachusetts 1784-1787; delegate to the Federal constitutional convention at Philadelphia in 1787 and to the State convention in 1788 which ratified the same; moved to New York City in 1788; member, New York assembly; elected to the United States Senate in 1789 and served from July 16, 1789, until May 1796, when he resigned to become United States Minister to Great Britain; Minister to Great Britain to 1803; unsuccessful Federalist candidate for Vice President of the United States in 1804; again elected to the United States Senate and served from March 4, 1813, to March 3, 1825; unsuccessful candidate for Governor of New York in 1816 and for President of the United States in 1816; again United States Minister to Great Britain 1825-1826; died in Jamaica, Long Island, N.Y., April 29, 1827; interment in the churchyard of Grace Church. His lovely wife, Mary, was born in New York, 17 October, 1769. She married Rufus King when she was 16 years old, on 30 March, 1786, at Trinity Church in Manhattan, the same church where she was baptized and her parents were buried. Mrs. Mary Alsop King was remarkable for her personal beauty. Her face was oval with finely formed nose, mouth and chin, with blue eyes, a clear brunette complexion, black hair and fine teeth. Her movements were at once graceful and gracious and her voice musical. She had been carefully educated. As an only child she was lavished upon without spoiling her character as the daughter of John Alsop, an opulent merchant whose large abilities, patriotism and well known integrity had secured his election to the Continental Congress which made the colonies independent. The latter years of her life, except while in Washington, were passed in Jamaica, Long Island. She died on June 5, 1819 in Jamaica. 9Stuart Paints the Pair

Mr. Rufus King |

Mary Alsop King |

Mr. Rufus King by Gilbert Stuart - 1819 |

Replica of Mrs. King by Trumbull - 1820 |

Footnotes

1 “Washington’s Headquarters Museum,” Morristown National Historical Park, NPS (2007) p. 12 2 “Certain Splendid House:” the Centennial History of the Washington Association of New Jersey, 1976, James Elliott Lindsley 3 “Gilbert Stuart,” Richard Mc Lanathan, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York, 1986, p. 93 4 Upon Stuart’s death, the Boston Athenaeum had a memorial exhibition of more than 200 of Stuart’s works. “Through a public subscription, a committee of trustees of the Athenaeum raised fifteen hundred dollars to purchase the unfinished portraits of President and Mrs. Washington, the painter’s only legacy to his family.” Ibid., p. 150. 5 The New York Times. Published February 21, 1895. Copyright The New York Times 6 “A Washington Portrait by Gilbert Stuart reveals the whereabouts of the long lost Portrait of Mrs. Rufus King” John Wilfred Dawson (1940), Morristown NHP Library. 7 Gilbert Stuart – Washington. www.americanrevolution.org/washstu.html 8 The Newark Evening News, February 22, 1962 9 “The Republican Court or American Society in the Days of Washington,” Rufus Wilmot Griswold, B. Appleton and Company, New York, 1854, p. 100. 10 “Washington Portrait” Dawson. 11 Ibid., pg 3. 12 http://senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Painting_31_00003.htmPopular Cities

Popular Subjects

Econometrics Tutors

AP Studio Art: 3-D Design Tutors

Accelerated Spanish Tutors

UK GCSE Italian Tutors

CTRS - A Certified Therapeutic Recreation Specialist Tutors

AP Latin Tutors

Entrepreneurship Tutors

OAE - Ohio Assessments for Educators Tutors

CSRM - Certified School Risk Manager Tutors

CLEP Introductory Sociology Tutors

High School Biology Tutors

UK A Level Computer Science/ICT Tutors

Tunisian Tutors

Slavic Tutors

SSAT Tutors

Medical School Test Prep Tutors

Business Plan Development Tutors

7th Grade Reading Tutors

4th Grade French Tutors

Mexican American Studies Tutors