Yankee Doodle and the Country Dance from Lexington to Yorktown

A Song, a Shot, and a Shock

On April 19, 1775, as British Regulars under General Hugh Percy marched out of Boston to reinforce those under fire from Lexington to Concord, they taunted the rag-tag Minutemen by playing "Yankee Doodle."

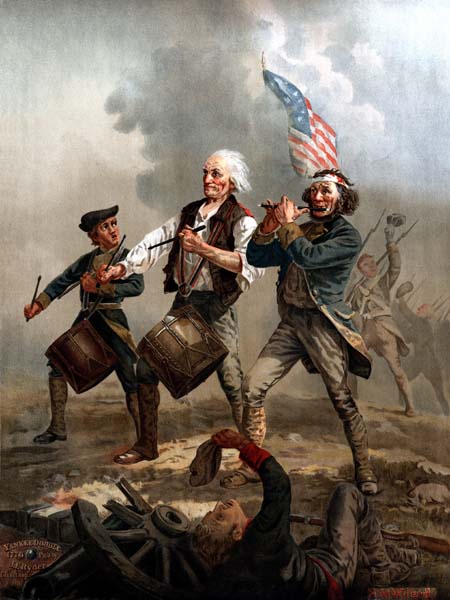

"Yankee Doodle" became the unofficial national anthem. On October 19, 1781, during Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, Washington’s army and his French allies were still playing "Yankee Doodle,"[3] while the shocked British played "The World Turned Upside Down." They had "learned to appreciate the true spirit of this American folk song, which portrays the Americans as cowards, yokels, and naifs, or which makes sexual jokes, or describes typical American holidays" (Lemay 461). "Yankee Doodle" became an expression of patriotic pride, national humor, and the Spirit of ’76. It helped win the Revolution.[4] It accompanied the shot heard round the world and the day George III’s empire was turned on its ear. It is our nation’s birthsong, our entrance music, our primal refrain, our song of ourselves before Walt Whitman’s barbaric yawp. Archibald Willard’s iconographic, cartoonish image, painted for the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, captures this spirit (Figure 1).Among the Minutemen was Thomas Ditson, who had been tarred and feathered by British soldiers a month earlier and paraded through Boston to the song.[1] By the end of the day, with the Regulars in full retreat, Ditson and the Americans were the ones singing "Yankee Doodle." According to the May 20, 1775, Massachusetts Spy, "When the second brigade marched out of Boston to reinforce the first, nothing was played by the fifes and drums but Yankee Doodle. . . . Upon their return to Boston, one asked his brother officer how he liked the tune now—‘D--n them!’ returned he, ‘they made us dance it till we were tired.’—Since whichYankee Doodle sounds less sweet to their ears." The metaphor of the Americans making the English dance to the song in retreat was instantly a popular satire.[2]

Figure 1. Yankee Doodle by Archibald MacNeal Willard (c. 1875)

When Willard painted this picture, every schoolboy knew the familiar (but not first) first verse from the "Visit to the Camp" version of "Yankee Doodle," printed c. 1775-1785 (Lemay 453):

Father and I went down to camp,

Along with Captain Gooding,

And there we see the men and boys

As thick as hasty pudding.

Every schoolboy knew the chorus, first printed in 1767 (Barton 54-55):

Yankee Doodle keep it up,

Yankee Doodle dandy,

Mind the music and the step,

And with the girls be handy.

Every schoolboy enjoyed singing the seemingly silly "standard stanza" that "probably dates from the vogue of the macaroni in the early 1770s" and that became the most popular verse, but not printed until 1842 (Lemay 439):

Yankee Doodle came to town

Riding on a pony,

Stuck a feather in his hat

And called it Macaroni.

After the Revolution, "Yankee Doodle" continued to be expanded and parodied.[5] New stanzas were invented, and original pre-Revolution and Revolution-era stanzas were forgotten, or their meanings lost. Everyone still sensed the spirit and the satire, but some of the old words (doodle, dandy, macaroni) and references (Captain Gooding, hasty pudding) had become obscure. If the 19th-century schoolmarm understood the 18th-century origins of the song, the cultural allusions, the etymologies, and the first-person voice (Father and I), she would have been shocked at what her pupils were singing (keep it up . . . And with the girls be handy). Even today, websites on "Yankee Doodle" are littered with misinformation and misinterpretations, some from the 1800s.

Lucy Locket, Dolly Bushel’s Fart, and Oliver Cromwell

In his 1909 Report for the Library of Congress, Oscar Sonneck traces the tune of "Yankee Doodle" to an English folk melody used for the popular "Kitty Fisher’s Jig" in New England twenty years before the Revolution. The words to the jig are preserved in the nursery rhyme "Lucy Locket" (Sonneck 100-101):

Lucy Locket lost her pocket,

Kitty Fisher found it,

Nothing in it, nothing in it,

But the binding round it.

Lucy Locket was a proverbial whore who appears in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728). Kitty Fisher (1738-1767) was an infamous London courtesan who gained celebrity through high-profile affairs starting in 1756. So, Royalists and Freemasons in New England may have popularized the jig to tease their Puritan neighbors. However it came to America, the tune was a familiar and obvious choice as the music for an original American song. The connection between "Lucy Locket" and "Yankee Doodle" is fixed by a verse printed in 1775:

Dolly Bushel let a fart,

Jenny Jones she found it,

Ambrose carried it to mill

Where Doctor Warren ground it. (Lawrence 52)

Though ignoring the Kitty Fisher echoes (lost/let, pocket/fart, Lucy/Kitty/Dolly/Jenny, found it/round it/ground it), both S. Foster Damon (1) and Leo Lemay (437-38) did use this parody to date the verse to just before Joseph Warren’s death at Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775.

The origins of the words to "Yankee Doodle" are not so easily discovered. Sonneck quotes numerous 19th-century accounts, including John W. Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia (1844), which he calls a "bouquet of historical gossip and blunder" (97). Several of Watson’s sources trace the tune and one verse back to as early as the first English Civil War (1642-1646) and a Cavalier song satirizing Oliver Cromwell. To support this implausable, anachronistic hearsay, which is now perpetuated across the internet, Watson cites "a writer in the Columbian Gazette" who claimed to have seen a song called "Nankee Doodle" in a collection "of a gentleman at Cheltenham in England, called ‘Musical Antiquities of England’, to wit":

Nankee Doodle came to town

Upon a little pony

With a feather in his hat,

Upon a macaroni.

According to Watson, the allusion is to Cromwell going into Oxford (Sonneck 98), perhaps in June 1646 to accept the surrender of the Royalists, riding on a small Kentish horse "with his single plume fastened in a sort of knot called a ‘macaroni’." Even if Nankee Doodle were a nickname the Cavaliers gave to Cromwell and the Roundheads (though no contemporary record supports this claim), it is hard to imagine Cromwell, the Puritan of Puritans, wearing feathers. None of the dozens of Google images of Cromwell shows him sporting a feather in his hat. Furthermore, macaroni is an 18th-century term for European affectations in dress, hairstyle, and manners, not a 17th-century knot.[6] Even early on, Edward F. Rimbault in his article "American National Songs" (1876) had doubts: "We must own to an entire want of faith in this story. The probability is that the tune is not much older than the time of its introduction into America" (Sonneck 103). Despite numerous undocumented web sites that identify Nankee Doodle as Cromwell, modern scholarship must conclude that they too are an internet "bouquet of historical gossip and blunder." Is Cromwell Yankee Doodle? No. Cromwell has nothing to do with "Yankee Doodle." As Sonneck said 101 years ago, "The ante-Cromwellian origin of ‘Yankee Doodle’ and its anti-Cromwellian use with all the embellishments that imaginative minds have added during the last seventy years may definitely be laid to rest" (114). Damon agrees, "The theory . . . has been discredited" (12).

Brother Raccoon, Pastor Pike, Ben Franklin, and the Freemasons

The first published text of "Yankee Doodle" is in the earliest American play, a ballad opera, The Disappointment; or, The Force of Credulity. A New American Comic-Opera, of Two Acts by Andrew Barton, Esq (by Thomas Forrest), printed in New York and Philadelphia in April 1767 (Lemay 442). The scheduled performance in Philadelphia was cancelled when management learned that it mocked some local personalities, including some Freemasons.[7] In Act I. Scene III of this satire of men’s gullability for get-rich-quick schemes, a dupe called "brother Racoon" (Barton 45) kisses his mistress and exits singing, to dig for buried treasure (Barton 52-55):

AIR IV. Yankee Doodle

O! how joyful shall I be,

When I get de money,

I will bring it all to dee;

O! my diddling honey.

Yankee doodle keep it up,

Yankee doodle, dandy;

Mind the music and the step

And with the girls be handy.

(Exit, singing the chorus, yankee doodle, &c.)

The stage direction ("chorus, yankee doodle, &c.") assumes everyone’s familiarity with the song. The "O! how joyful shall I be" stanza was no doubt composed by Forrest and illustrates the power of the catchy tune to inspire new stanzas, sometimes dirty. The "Yankee doodle, dandy" refrain looks related to the seminal lines "Boston is a Yankee town, / Sing Hey Doodle Dandy" first printed on "The Lexington March" broadside in 1775. Raccoon’s air proves that the song and chorus were popular beyond New England a decade before the Revolution.

How old and mysterious its origins are we can only imagine from the 1730 manuscript tune-book of Reverend James Pike, pastor in Somersworth, New Hampshire. One page contains two musical scores. The first is to "Freemason’s March," and below it is "Yankey Doodle" (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A pair of songs in Pastor Pike’s 1730 tune-book (Lawrence 33)

Pike’s score for "Yankey Doodle" is very different than the score for Raccoon’s "Yankee Doodle" in The Disappointment (Figure 3). Surprisingly, however, the first 24 notes above Raccoon’s verse almost match the first 19 notes of Pike’s "Freemason’s March."

Figure 3. Raccoon’s song (1767) in The Disappointment (Barton 52-54)

Remarkably, Pike’s entire score to "Yankey Doodle" almost exactly matches the notes on an early broadside (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The musical score to "Yankee Doodle" c. 1782-1794 (Lawrence 52)

Pike’s scores could be a missing link between "Yankee Doodle" and the Freemasons. Was "Yankee Doodle" a Masonic march? Maybe. Masonic bands still play it today. The connection between the song and Freemasonry deserves investigation. For instance, the first line on the earliest broadsides is "Brother Ephraim sold his cow," which could suggest that he is a member (Brother) of the fraternity. Then right away he is characterized as "an arrant Coward." Similarly, in The Disappointment, Raccoon is a cowardly, scheming Freemason. In Act I. Scene IV, Hum says, "we are all to meet at the Ton, precisely at six" (60). In Act II. Scene I, Moll Placket tells another of her lovers, Topinlift, how Raccoon learned of Blackbeard’s treasure:

Plac. . . . the papers were preserv’d in the family, till they were sent to Mr. Hum—and you must know Raccoon is a free-mason, so he is to assist him, and they are to go shares.

Top. How the devil do you know that Hum’s a free-mason.

Plac. Why I suppose so, for they always call one another brother—and they keep this business as secret as their masonry—but I wheedled him out of it, in spite of all their cunning. (Barton 86).

Referencing Patricia Virga’s dissertation "The American Opera to 1790" (1980), Carolyn Rabson raises questions about the play that could also be asked about "Yankee Doodle":

The significance of the Masonic symbols and rituals that occur throughout the play has yet to be explained. Virga has documented the strong correspondence between places and events in The Disappointment and Masonic activities in Philadelphia, and between the play’s characters and members of the Tun Tavern Lodge. Whether this is meant as a satirical thrust against Freemasonry or against only certain Masonic lodges, or whether it is intended to extol the Masonic movement as an agent of social progress is difficult to determine. (23)

Initiated in 1731, Ben Franklin was a Grandmaster at the Tun Tavern Lodge (though in England in 1767). When he walked into Philadelphia on October 6, 1723 at age 17, he looked like Yankee Doodle, except with a bread roll stuck under each arm rather than a feather stuck in his hat. Was Franklin Yankee Doodle? Yes and No. On April 5, 1774, Franklin wrote "An Open Letter to Lord North" in the persona of A Friend to Military Government, who proposes that Prime Minister North impose martial law on the colonies.[8] This Friend assures North that the colonialists are cowards: "The Yankey Doodles have a Phrase when they are not in a Humour for fighting, which is become proverbial, I don’t feel bould To-day." Franklin is satirizing British ignorant contempt for Americans, not mocking his brothers and fellow patriots.

Other famous Freemasons show up in early texts. For example, Joseph Warren, who ground Dolly Bushel’s fart in "The Lexington March," was a Freemason. Some verses in "A Visit to the Camp" satirize a Virginia Freemason not yet beloved in New England:

And there was captain Washington,

And gentlefolks about him,

They say he’s grown so tarnal* proud, *eternal

He will not ride without them.

He got him on his meeting clothes,

Upon a slapping stallion,

He set the world along in rows,

In hundreds and in millions.

The flaming ribbons in his hat,

They look’d so taring* fine ah, *tearing; grand

I wanted pockily* to get, *particularly?

To give to my Jemimah. (Lawrence 61)

As "Yankee Doodle" became a symbolic battlefield, the British added verses, some threatening Freemasons leading the rebellion:

Yankee Doodle’s come to town

For to buy a firelock

We will tar and feather him,

And so we will John Hancock. (Damon 5)

Others, more angry, were added after the British Pyrrhic victory at Bunker Hill:

But as for that King Hancock,

And Adams, if they’re taken,

Their Heads for signs, up high we’ll hang,

Upon a hill call’d Bacon. (Lawrence 57)

Was Yankee Doodle a Freemason? To be one, he needed but ask one.

Dr. Schuckburgh, "The Lexington March," and Ephraim Williams

According to the earliests accounts (Sonneck 95-97), Dr. Richard Shuckburgh, a British army surgeon during the French and Indian War, composed the first verses to "Yankee Doodle" to ridicule the motley colonial militia that straggled in to join the British at Albany in 1755. This attribution is an arguable assumption now repeated matter-of-factly across the internet. Sonneck’s source was "The Origin of Yankee Doodle" published in a Farmer and Moore’s Collections in July 1824 (vol. 3, 217-18) by an anonymous reporter whose source was "an old file of the Albany Statesman, edited by N. H. Carter," who cites "the recollection of some of our oldest inhabitants" and "my worthy ancestor, who relates to me the story."[9] The reliabilty of this thrice-removed hearsay is doubtful.

Sonneck provided a facsimile of the earliest broadside he knew (234-35), printed in London by Thomas Skillern, entitled "Yankee Doodle; or, (as now christened by the Saints of New England) The Lexington March"[10] (Figure 5). Sonneck expurgated the text because "Stanzas sixth and seventh are too obscene for quotation" (132), and he dated the broadside 1777-1799. Lemay dated it 1782-1794 and found Skillern’s source on a broadside in the Huntington Library, "printed in London in the early summer of 1775, when news of the battles at Lexington and Concord was still the latest word from America, and before the news of the battle of Bunker Hill reached London in mid-August" (437-38).[11] The Huntington and Skillern broadsides are almost identical.[12]

The sundry attempts to explicate these stanzas need not be surveyed here. Most on-line commentaries just repeat earlier questionable, undocumented interpretations. For example, "Brother Ephraim" is commonly identified as Colonel Ephraim Williams of the Stockbridge, Massachusetts militia, who was killed on September 8, 1755, at Lake George, New York:

Brother Ephraim sold his Cow

And bought him a Commission,

And then he went to Canada

To fight for the Nation;

But when Ephraim he came home

He prov’d an arrant Coward,

He wou’dn’t fight the Frenchmen there,

For fear of being devour’d.

However, not Sonneck, Damon, nor Lemay connect this "arrant Coward" to the French and Indian War hero. Ephraim Williams was neither a coward nor a Freemason, or a hot-headed yokel who needed to sell his cow to pay for a commission in the British army. Was Ephraim Williams Yankee Doodle? Yes and No. The facts do not fit the character.

Figure 5. The c. 1782-1794 Skillern broadside (Lawrence 52)

In fact, Damon (2) and Lemay agree that the stanzas about Ephraim going to Canada, as well as the related stanza about simple-minded Aminadab returning with news of an American victory at Cape Breton, refer to the capture of Fort Louisburg during King George’s War on June 16, 1745. Lemay concludes that the stanzas "were in oral circulation as a song by the end of the 1740s" and that "their intention is to burlesque the English attitudes toward the American militia" (447). In 1745 Ephraim Williams was a captain defending Fort Massachusetts, not a deserter cowering at home in fear of reported cannibalism by the French and their native allies. Removing all association, later versions replaced the respected name Ephraim with a man, as in the "Yankee Song" broadside:

There is a man in our town,

I’ll tell you his condition,

He sold his Oxen and his Cows

To buy him a commission.

When a commission he had got

He prov’d to be a coward,

He durst not go to Canada

For fear of being devoured.

Damon believes that these stanzas are pre-Revolution because "the ‘coward’ lines were not yet taboo" (4). As he points out, when the Yankees reclaimed their song during the Revolution, "the ‘coward’ lines were omitted. In Royall Tyler’s The Contrast (acted 1787, published 1790), Jonathan starts singing the song, but when he comes to the forbidden lines, he interrupts himself with a ‘No, no, that won’t do’" (5). Jonathan’s verse starts, "There was a man in our town, / His name was—" (Act Third, Scene I), but he realizes the bad taste of the joke and says to Jenny, "you would be affronted if I was to sing that." Was the man’s name Ephraim Williams? No. Over time, the association of the word coward with the name Ephraim was all but forgotten.

What remains to explain is the pose of the Yankee as a cowardly, stupid bumpkin. Quoting a letter dated "Roxbury [Massachusetts], April 26, 1775," which refers to "Yankee Doodle" as "a song composed in derision of the New Englanders, scornfully called Yankees" (95), Sonneck supports this traditional interpretation: "no disagreement seems possible on the point that this text was not written by a New Englander, but can only have been penned by either an American Tory or a Britisher" (133). In disagreement, nonetheless, Lemay argues that the tone is ironic and that the "ostensible satire of the provincial American militia is a perfect example of a dominant tradition of American humor" (444). Citing such examples as "New England’s Annoyances" (c. 1643) and Ebenezer Cook’s The Sot-Weed Factor (1708), Lemay concludes, "Americans learned to reply to English snobbery by deliberately posturing as unbelievably ignorant yokels. Thus, if the English believed the stereotype, they would be taken in by the Americans. And, of course, if they were taken in, the Americans had reversed the snobbery and proven the English were credulous and foolish" (444-45). In other words, the British speaker seemingly satirizing America is actually the subject of American satire of English smugness, as in Franklin’s "An Open Letter to Lord North." Damon’s theory that "the explanation of the original fondness of the British for the song lies undoubtedly in the ‘coward’ lines" (5) supports Lemay’s argument for an American burlesque of English condescension.

To bolster his evidence for the American origins of "Yankee Doodle," Lemay points to stanzas from "The Lexington March" that "describe activities at early American frolics" (447) and "the eating, drinking, and sexual escapades that went on at all frolics" (450):

Christmas is a coming Boys

We’ll go to Mother Chases,

And there we’ll get a Sugar Dram,

Sweeten’d with Melasses.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Punk in Pye* is very good *Pumpkin pie

And so is Apple Lantern;

Had you been whipp’d as oft as I,

You’d not have been so wanton.

As Lemay says, such stanzas are "characteristic folk poetry, . . . simultaneously poetry, music, and dance" (451):

Stand up Jonathan

Figure in by Neighbor,

Vathen* stand a little off *Vather; Father

And make the Room some wider.

"To suppose that these stanzas dealing with colonial holidays were composed by some British officer in derision of the Americans is simply absurd. . . . These stanzas of indubitably American folk origin were evidently, like the Cape Breton group, in popular circulation by the late 1740s" (Lemay 451). Damon’s explanation of some errata supports an American original (1):

The publication would seem to be part of the pro-American propaganda in England which was very active in 1775. The source of the text was Boston, as several references to that city indicate; and the other references to Cape Cod, Nantasket, and Lynn are all from Massachusetts Bay. But the English printer was not familiar with the Yankee dialect. Twice he misread "Vather" (father) as "Vathen", which he supposed was somebody’s name; and he had no idea what the "Punk" was that was so good "in Pye".

"Yankee Song," Rum, Molasses, Corn, and a Riddle

Other American holidays and folk customs are described in related stanzas and in the chorus of "Yankee Song," a broadside which Lemay dates to the 1810s (Figure 6), "But the text, which may have been printed from an earlier broadside or manuscript, is pre-Revolutionary" (441).[13]

One stanza in particular in "Yankee Song" connects the two broadsides:

Lection time is now at hand,

We’re going to uncle Chace’s,

There’l be some a drinking round

And some a lapping lasses.* *molasses

Figure 6. Pre-Revolution verses in the c. 1810s "Yankee Song" broadside (Lawrence 34).

Mother Chase’s Christmas parties in "The Lexington March" and uncle Chace’s election-day parties seem to have been local traditions, probably at a family tavern also referred to in The Contrast. Jonathan says, "if I was with Tabitha Wymen and Jemima Cawley down at father Chase’s, I shouldn’t mind singing this all out before them." So, "Yankee Doodle" was also a drinking song. Punch made from rum and molasses was a colonial favorite. Lawrence follows this interpretation: "the ‘lasses’ that were lapped at the ‘lection’ festivities at ‘uncle Chace’s’ were the kind from which rum was distilled" (33). No doubt the local lads did lap up shots (drams) of rum and ’lasses, but considering the many sexual jokes and puns in the folksong, they might also have enjoyed "lapping" the girls.

The most archetypal American festival in "Yankee Song" is the corn-husking bee:

Husking time is coming on

They all begin to laugh sir—

Father is a coming home

To kill the heifer calf sir.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Now husking time is over

They have a duced* frolic, *deuced; devilish

There’l be some as drunk as sots

The rest will have the cholic.

CHORUS.

Corn stalks twist your hair off,

Cart wheel frolic round you,

Old fiery dragon carry you off,

And mortar pessel pound you.

Lemay shows that "husking frolics had developed into a colonial institution with their own nomenclature by the late 17th century," and he cites ample "evidence for husking as a social and nationalistic festival" (448). For example, as the English visitor Edward Ward wrote in A Trip to New England(1699), "Husking of Indian-Corn, is as good sport for the Amorous Wag-tailes in New England, as Maying amongst us is for our forward Youths and Wenches" (Lemay 448). This harvest festival, descended from ancient fertility rituals and related to American Indian harvest songs and legends of the Corn Mother (Lemay 449), further proves that "Yankee Doodle" was composed by Americans, not an English satirist. Lemay continues, "The Corn Stalks chorus is especially interesting because of its ritualistic identification with the corn. . . . The spirit of the corn itself is speaking, describing the death and transmutations which it undergoes to bring life to man" (448). The chorus is a riddle, the answer to which is corn. The first line, ". . . twist your hair off," refers to detasseling or desilking the corn. The "Cart-wheel frolic" is both the busy wheel carts and the couples dancing around the corn. The "Old fiery dragon" is the burning of the husks and cobs, or parching the kernels, or drinking corn whiskey. The "mortar pessel" pounds the dry kernels into cornmeal. "There can be no doubt that the Corn Stalks chorus celebrates the ritual sacrifice of the god of the harvest—and that in New England in the eighteenth century this was enacted at a frolic rather than at a religious ceremony" (Lemay 450). This interpretation also connects to "Father is a coming home / To kill the heifer calf sir."

"The Farmer and his Son’s return from a Visit to the CAMP," Edward Bangs, and "I"

The final American motifs in "Yankee Song" are also in related verses on the c. 1775-1785 broadside of "The Farmer and his Son’s return from a visit to the CAMP" (Figure 7).[14] Sonneck (135-36), Damon (5-8), and Lemay 452-53) reference a quick succession of a dozen broadsides of "A Visit to the Camp," most retitled "The Yankee’s Return from Camp." Its 15 verses became the standard text in American literature anthologies in the 20thcentury as the supposedly original and thenceforth canonical "Yankee Doodle."[15]

Figure 7. The c. 1775-1785 "Visit to the Camp" broadside (Lawrence 61)

Like "The Lexington March" and "Yankee Song," "A Visit to the Camp" has been read as English satire, but Sonneck (140-42) and Damon (5) liked the tradition that it was by a Minuteman named Edward Bangs in 1778. Accepting the "authority of Edward Everett Hale," Damon declares, "This version came from a single pen and can definitely be attributed to a Harvard sophomore, Edward Bangs" (5). Sonneck observed: "If we turn to the text itself, it clearly reveals an American origin. It is so full of American provincialisms, slang expressions of the time, allusions to American habits, customs, that no Englishman could have penned these verses" (141). Lemay agrees (453-54): "they would never have been written as a satire on the Americans—not because they are so knowledgeable about Americans but because they are so good-natured and because they really mock the condescending attitudes toward Americans."

The attribution of these verses to Edward Bangs rests on a note from Judge Thomas Dawes to Edward Everett Hale’s father, editor of the Boston Daily Advertiser (Lemay 455):

Boston, 25th June 1824

Sir: —The Eleven Yankee-Doodle stanzas in your paper of yesterday and perhaps the additional ones were the sudden effusions of my departed classmate, Edward Bangs, father of the present secretary of Massachusetts, written when a student under Theophilus Parsons, in 1778. I think he wrote them when on a visit to Cape Cod, his native place.

Yours with much regard

Thomas Dawes

Edward Bangs answered the call in Middlesex on April 19, so the story makes good myth, but Lemay has doubts. Was Edward Bangs Yankee Doodle? Yes and No. Eight stanzas in "A Visit to the Camp" are versions of verses in "Yankee Song." As Lemay notes, the stanzas common to both texts "are usually better, aesthetically, in the Yankee Song broadside. Therefore, if Bangs did revise the stanzas, he made them worse rather than better. The logical conclusion is that the stanzas were not revised by Bangs, but that the versions in the usual Visit to camp broadsides represent the result of deterioration while in the oral tradition" (460). Damon concedes:

Bangs was credited with the entire song, but now it is evident that he built his poem on the earlier "Yankee Song", locating the camp at Cambridge, and mounting Washington on the slapping stallion. He pulled the whole narrative together into a unit, omitting any superfluous stanzas about the Yankee relatives and customs. The hero is now definitely not an ignorant yokel but a naïve, inquisitive, and timid boy who flees home in a panic, thus bringing the song to a satisfactory conclusion and giving it the popular title of "The Yankee’s Return from Camp." He also added stanzas 2 and 3 about ’Squire David (which were not too successful), and stanza 7 about Cousin Simon. Bangs also provided the new chorus. (5)

The chorus, of course, comes long before in The Disappointment (1767). Lemay closes the question of authorship of this folksong:

knowing that the stanzas in the Yankee Song broadside are evidently pre-Revolutionary, I see little reason to believe that Edward Bangs had anything to do with any "Yankee Doodle" texts. Judge Dawes may have learned a Visit to Camp version of "Yankee Doodle" from Bangs, and he evidently believed (over forty years later) that Bangs said he wrote "Yankee Doodle." I conclude that the Visit to Camp stanzas—like the Cape Breton stanzas and the Corn Stalks stanzas—are traditional, that they antedate by at least two decades their supposed composition by Edward Bangs in 1778 at Cape Cod, and that they are of American origin. (460)

The stanzas tell a scared yet curious country boy’s story of his first day initiation at a Continental army camp. Sonneck pointed to the stanzas about Washington and wrote, "With this allusion the conjecture becomes fairly safe that the text of ‘Father and I went down to camp’ originated at or in the vicinity of the ‘Provincial Camp,’ Cambridge, Mass., in 1775 or 1776" (142).[16] Lemay puts the setting in context: "The persona and locale reflect two traditions in colonial American humor" (452). First is the same pose as an unbelievably naive bumpkin used in the Cape Breton stanzas of "The Lexington March." Second is the comical description of a colonial militia training day, "a standard subject for humor."[17]

The comedy in "A Visit to the Camp" is not so much the setting and military images as it is the first-person speaker’s narrative, language, metaphors, and character development. The first verse sets the tone of his voice and his situation:

Father and I went down to camp,

Along with Captain Gooding,

And there we see the men and boys

As thick as hasty pudding.

The boy has joined his family and the rest of Captain Gooding’s local militia company for joint training with other units. He is proud to serve under Captain Gooding, who personifies the good American officer. He is proud to due his duty like the many other men and boys. The crowd at the camp so impresses him that he must try to convey his wonder, but he has only his childhood experiences on the farm for comparison, so he uses a distintly American simile, "As thick as hasty pudding" (cornmeal mush). Likewise, almost in riddles, he describes a cannon as "a swamping gun, / Large as a log of maple," a bayonet as "a crooked stabbing iron," a mortar as "a pumpkin shell, / As big as mother’s bason," and his future instrument, a drum:

I see a little barrel too,

The heads were made of leather,

They knock’d upon’t with little clubs,

And call’d the folks together.

Though cautious, he must investigate the big gun that "makes a noise like father’s gun, / Only a nation louder."

I went as nigh to one myself,

As ’Siah’s underpinning;

And father went as nigh again,

I thought the duce* was in him. *deuce; the devil

Cousin Simon grew so bold,

I thought he would have cock’d it,

It scar’d me so I shriek’d it off,

And hung by father’s pocket.

"Yankee Song" goes, "I went so nigh to get a peep / I saw the under-pinning," which makes more sense, but the sharp boy’s courage is the same, even if he naturally hid behind his father when they prepared to fire it.

His initiation ends with a glimpse of the cost of war and of his own mortality:

I see another snarl of men,

A digging graves they told me,

So tarnal long, so tarnal deep,

They ’tended they should hold me.

It scar’d me so I hook’d it off,

Nor stopt as I remember,

Nor turn’d about ’till I got home,

Lock’d up in mother’s chamber.

The joke is that the eternal long and deep graves are probably just trench latrines, and the snarling men are just teasing the boy as part of his rite of passage. When he gets the joke, he will see his youth. For now he returns to "mother’s chamber," where he first heard "Yankee Doodle" as "the nurse’s lullaby" (Sonneck 109). Psychologically, he returns to the safety and security of the womb. But, he then "turn’d about," that is, thinks back on his experience. When he emerges tomorrow and goes back to camp, he will be a step closer to the boy in Archibald Willard’s painting. This boy will be like the kid remembered in William Gordon’s History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States (1788). As Lord Percy’s brigade marched toward Lexington to the step of "Yankee Doodle," a farmer’s son spoke up: "A smart boy observing it as the troops passed through Roxbury, made himself extremely merry with the circumstance, jumping and laughing, so as to attract the notice of his lordship, who, it is said, asked him at what he was laughing so heartily; and was answered, ‘To think how you will dance by and by to Chevy Chace.’ It is added, that the repartee stuck by his lordship the whole day" (vol. I, 312. Web). Aptly, the boy was alluding to a ballad about the defeat of Henry "Hotspur" Percy (Lord Percy’s ancestor) by the Scots in 1388. This Yankee Doodle boy will be reborn from mother’s chamber as a future Thomas Ditson, Edward Bangs, Captain Gooding, Ben Franklin, or George Washington.

Song, Society, and the American Self

Folksongs and country dances unite regional groups. Singing and dancing are communal activities that symbolize cultural harmony and social order. "Yankee Doodle" helped bring together an aspiring nation of people on the move, men and women, white and black. Demonstrating its popularity with both sexes, in The Contrast Jenny assures Jonathan, "Oh! it is the tune I am fond of; and if I know anything of my mistress, she would be glad to dance to it." When he stops singing after three verses from "A Visit to the Camp," she says, "Is that all! I assure you I like it of all things." Jonathan replies, "No, no; I can sing more, some other time, when you and I are better acquainted, I’ll sing the whole of it—no, no—that’s a fib—I can’t sing but a hundred and ninety verses; our Tabitha at home can sing it all."[18] Moreover, in his ode "Independence Day" (1796), Royall Tyler includes "our brother negroes" in the celebration:

To day we dance to tiddle diddle.

—Here comes Sambo with his fiddle;

Sambo, take a dram of whiskey,

And play Yankee doodle frisky.

Yankee Doodle is the young American everyman. His song is self-expression, a song of his growing self-awareness of himself as distinct from his Old World heritage. It is a song of self-confidence and self-satire, sung as proudly as James Cagney sang and danced in 1942,

I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Yankee Doodle, do or die,

A real live nephew of my Uncle Sam,

Born on the Fourth of July.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I am the Yankee Doodle Boy.[19]

Works Cited

Barton, Andrew. The Disappointment: or, The Force of Credulity (1767). Ed. by Jerald C.

Craue and Judith Layng. Recent Researches in American Music, vol. III & IV. Madison: A-R Editions, 1976: 52-55.

Cohen, Joel. "Program Notes" to Liberty Tree: American Music 1776-1861. Boston Camerata.

Mechanics Hall, Worcester, MA. 15-19 September, 1997. CD. Web.

Damon, S. Foster. Yankee Doodle. Providence, RI, 1959.

Franklin, Benjamin. "An Open Letter to Lord North." The Public Advertiser (London, April 15,

1774). Web.

Fischer, David Hackett. Liberty and Freedom. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lawrence, Vera Brodsky. Music for Patriots, Politicians, and Presidents: Harmonies and

Discords of the First Hundred Years. New York: Macmillan, 1975.

Lemay, J. A. Leo. "The American Origins of "Yankee Doodle." William and Mary Quarterly 33

(July 1976): 435-64.

Rabson, Carolyn. "Disappointment Revisited: Unweaving the Tangled Web, Part I." American

Music 1 (Spring 1983): 12-35.

Sonneck, Oscar George Theodore. "Yankee Doodle." Report on "The Star-Spangled

Banner""Hail Columbia" "America" "Yankee Doodle." Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909: 79-156.

Tyler, Royall. The Contrast: A Comedy. New York: Dunlap Society, 1887. Web.

"Yankee Doodle." The Literature of the United States. Eds. Walter Blair et al. Chicago: Scott, Foresman, 1946. 277-78.