The Mapmaker of Mount Vernon

By Edward J. Redmond Senior Reference Librarian Geography and Map Division, Library of CongressBeginning with his early career as a surveyor and throughout his life as a soldier, planter, businessman, land speculator, farmer, military officer, and President, Washington consistently relied on and benefited from his knowledge of maps. Between 1747 and 1799 Washington personally surveyed more than 225 tracts of land comprising more than 80,000 acres in 37 different locations, mainly on the western frontier of Virginia. At one time or another Washington personally held title to nearly 70,000 acres of land in Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Kentucky and the District of Columbia. The maps he personally prepared include roughly drawn field surveys, route maps, cadastral surveys, city plans, architectural and fortification plans, and finished survey plats.George Washington's activities as leader of the Continental Army and first President of the United States have been documented over the last two centuries by countless well-meaning historians and biographers. Many of these biographies, particularly those published in the nineteenth century, have distilled, rightly or wrongly, Washington's life into several readily identifiable themes; an unparalleled honesty, courage under fire, tremendous self-discipline, and strong, silent leadership. While these traits describe elements of Washington's character which contributed to his success there is another crucial factor essential to understanding Washington (and all but overlooked by his leading biographers); a lifelong interest in cartography and geography.

These items range from Washington's first survey exercise in 1747 to a 1799 survey done less than five weeks before his death. Additionally, an inventory of Washington's library taken shortly after his death included more than 90 maps, atlases, and geographic works. The library inventory included more than ninety maps and atlases including John Henry's 1770 Map of Virginia; Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson's Map of Most Inhabited Part of Virginia; Reading Howell's 1777 Map of Pennsylvania, Thomas Hutchins' Map of the Western Part of Parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland and North Carolina; Lewis Evans' Map of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Delaware; "Sundry Plans of the Federal District" (Including "One Large Draft"); Thomas Jefferys' West India Atlas and American Atlas; "Molls Atlas"; [William Faden's] "North America Atlas"; Christopher Colles' 1789 Survey of the Roads of the United States, and Jedidiah Morse's 1789 American Geography. Today, this collection of maps and atlases are highly collectible and could be found on any serious map collector's wish list. [i]

Despite the prominence of maps in Washington's life, the vast majority of his biographers have paid little attention to his cartographical associations. For example, the Library's collections include more than 1,500 works related to Washington, but only a handful of titles related to the impact of Washington's frontier experience, and one title specifically devoted to Washington's maps.[ii]

The George Washington Atlas, published in 1932 by the George Washington Bicentennial Committee, was the first attempt to compile a bibliography of maps drawn or annotated by George Washington. Conceived as part of the nationwide observances marking the 200thanniversary of Washington's birth, the atlas' compiler, Colonel Lawrence Martin, Chief of the Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, identified 110 extant maps drawn or annotated by Washington, including several not previously attributed to Washington. Since 1991, additional items not included on the 1932 census have been uncovered bringing a remarkable total of more than 150 extant maps and surveys preserved in institutions around the world. Nearly one third of the extant items are housed in the Manuscript and Geography & Map collections at the Library of Congress. [iii]

For our purpose's Washington's cartographic career can be divided into three periods; public surveyor, planter, and private land speculator. Undoubtedly, Washington's close association and practical knowledge of the land first tasted by Washington on the wilds of the Virginia frontier and refined during his seemingly endless quest for land (and its corresponding social status) contributed to his development from surveying apprentice to one of the most important men in Virginia and, ultimately, the United States.

Washington As Public Land Surveyor

George Washington was born February 22, 1732, to Augustine and Mary Ball Washington at Popes Creek Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on Virginia's Northern Neck. In 1735 the Washington family moved from Popes Creek to a site at the junction of Little Hunting Creek and the Potomac river, where they lived until moving to Ferry Farm on the Rappahannock River in 1738.

In 1743 George's father, Augustine, died. At the age of 11 years old, young George Washington was set to inherit the small Ferry Farm where he lived with his mother and siblings, while his older half brother Lawrence inherited the larger farm at the junction of the Little Hunting Creek site which he named in honor of his commanding officer Edward Vernon, Mount Vernon. Washington had little use for the meager surroundings at the Ferry Farm plantation and after a brief flirtation with the idea of a career in the Royal Navy, set to studying geometry and surveying using a set of surveyors' instruments from the store house at Ferry Farm.

Among the earliest maps attributed to Washington are sample surveys prepared during his informal schooling found in his 'School Boy Copy Books' in Washington Papers. The schoolbooks include lessons in geometry and several practice land surveys Washington prepared at the age of sixteen, including a survey of his brother Lawrence's turnip garden, with whom George had been spending more and more time at the Little Hunting Creek estate.

Early in 1748, with only the practice surveys under his belt, Washington accompanied George William Fairfax and James Genn, Surveyor of Prince William County, on a month long trip west across the Blue Ridge Mountains to survey land for Thomas, Lord Fairfax, 6th Baron Cameron. Although the surveys were actually performed by the more experienced members of the party, the trip was Washington's formal initiation to the field and led him to pursue the profession. The trip also marked the beginning of a lifelong relationship between Washington and the extremely powerful and influential Fairfax families that gave the young surveyor virtually complete and unfettered access to Virginia society.

In July 1749, at 17 years of age, largely through his cultivated influence of the Fairfaxes, Washington secured an official appointment as the county surveyor for the newly created county of Culpeper. During the next three years (1749 - 1752) on the frontier Washington personally surveyed and platted nearly 200 tracts in Culpeper, and Frederick counties.[iv]

The Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, has several examples of Washington surveys including a November 17, 1750 survey plat of 460 acres along the Great Cacapon River for John Lindsey an April 3 1751 survey for Owen Thomas along the South side of Bullskin Run in Frederick County.

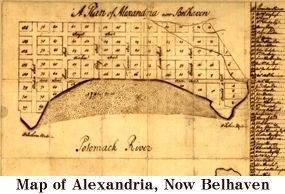

In addition to the public surveys done on the western frontiers of the Northern Neck, Washington prepared two remarkable maps of the area that became the city of Alexandria, Virginia. The earliest is the "Plat of the Land whereon now Stands the Town of Alexandria," drawn in 1748. As the title suggests, the map is a simple outline of the future town annotated with the land area" Area 51 acres, 3 Roods, 31 Perch. "The site map includes the location of existing structures including a tobacco inspection warehouse and notes on the suitability of land within the proposed town. The map also includes information vital to the operation of any port city, namely soundings and shoal locations in the Potomac River. The lack of a street grid indicates that the map was likely drawn before July 1749, the formal incorporation of the town of Alexandria.

The second map, entitled "Plan of Alexandria, Now Belhaven" includes a street grid and the names of lot holders who purchased lots in the new city. The list of lot owners included Washington's older half-brothers, Lawrence and Augustine, William Fairfax, and George William Fairfax. Based on these maps, some[v] have erroneously concluded that Washington personally designed or was at least heavily involved in the city's formation. While both maps are clearly in Washington's hand, there is no documentary evidence to backup this claim. As was the case with the maps prepared during his first surveying trip, it is more likely that Washington based these on or copied directly from originals drawn by John West, Jr., Deputy Surveyor of Fairfax County, the man generally recognized as performing the actual surveys. Taken together these maps may be the earliest extant 'before and after' plans of colonial towns, representing span of less than six months. Based on the lot owners the map was likely prepared in September 1749 by Washington to keep his brother Lawrence, then in London, abreast on the town's incorporation. [vi]

Washington's three years of surveying provided valuable experience which helped his meteoric rise in colonial Virginia society. Not only did he experience frontier life firsthand but the careful measurement and attention to detail necessary in surveying and platting may have helped develop Washington's extraordinary self-discipline, which naturally carried over into crucial organizational skills used in his private, military, and political lives.

The frontier years were also an introduction to diplomacy and politics. He learned how to negotiate and deal with all kinds of people, the large landowner, the small landowner, the prospective landowner, county clerks, chain men, and markers. It should be noted however, that the young surveyor was not exactly starting at the entry level. As a Northern neck county surveyor he worked directly for Lord Fairfax and William Fairfax, the same men who owned the Northern Neck and facilitated Washington's appointment as the Surveyor of Culpeper County from the College of William and Mary. (An appointment which Washington received without taking a test or even visiting Williamsburg.) Additionally, the family seat of the Fairfax family, Belvoir, was only short distance downstream from Mount Vernon; his half brother Lawrence married Anne Fairfax; and one of his closest friends was George William Fairfax. In other words, George had friends in all the right places and access that others did not.

Nevertheless, Washington was an extremely productive surveyor. He established a reputation for fairness, honesty, and dependability while making favorable impressions on the movers and shakers of colonial Virginia. The surveyors intimate knowledge of the land and official capacity as a representative of large land holders such as the Fairfaxes made their participation politically and practically crucial for the large land companies such as the Loyal Land Company of Virginia, the Ohio Company, and the Mississippi Land Company. Not only did Washington receive substantial fees for surveying, but he discovered first hand how to speculate successfully in land, an especially important consideration in colonial America, where land equaled power. [vii]

By the end of his public surveying career Washington had accumulated more than 2,000 acres of land along the frontier- approximately the same amount of land his brother Lawrence had inherited at Mount Vernon[viii]. All of a sudden George's position in society was almost equivalent (at least in terms of acreage) as his half brother, Lawrence, a military hero.

Washington As Mount Vernon Planter

In 1754 Washington gained title to the Mount Vernon estate from his half-brother's widow. For the next 45 years Washington called Mount Vernon home and transformed it from a relatively small unprofitable venture into a vibrant working plantation. Like most Virginians Washington originally grew tobacco but he soon discovered that the soil at Mount Vernon did not produce good yields, and eventually concentrated on growing corn and wheat. To process the crops Washington also built and operated a large gristmill and a revolutionary sixteen sided barn used for threshing wheat on the property. In addition to farming operations Washington also built a mill and large greenhouse at Mount Vernon and even operated a ferry and successful fishing operation on the Potomac River. [ix]

The expansion of Mount Vernon from a small farm into an 8000 acre working plantation was Washington's most ambitious step towards securing a place among the Virginia elite. The growth did not happen all at once, instead, it took more than 20 different land transactions over a period of thirty-two years. The process of acquiring tracts began in 1757, two years before his 1759 marriage to Martha Custis, and required skillful negotiations, patience, assertiveness, money, legal threats, and a fair amount of dumb luck. [x]

To demonstrate the complicated nature of acquiring property (and the usefulness of a surveying background) let's focus on the story behind the purchase of Clifton Neck, better known as the River Farm.

William Clifton lived on a piece of land known as Clifton's Neck across Little Hunting Creek next to Mount Vernon. Although Clifton operated a ferry and tavern on the property, he apparently was not the best businessman. In 1759 he was forced to sell the land to satisfy his creditors and, conveniently, George Washington was one of the commissioners appointed to oversee the liquidation of the property. Clifton and Washington agreed on a price of £1,150 for the 1,806 acre tract on the northern border of the estate. Less than a day later, however, Clifton agreed to sell the same tract of land to another neighbor, Thomson Mason, for a slightly higher price. Despite Clifton's original agreement and a series of angry letters, (Washington called him a "thoroughly paced rascal" and complained of his "scuffling behavior") Washington wound up paying £1,250 sterling to secure the land for himself. [xi]

The Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, has two manuscript maps of the land purchased from Clifton drawn by Washington. The earliest is a map Washington copied in 1760, presumably during the purchase of the property. Titled Plan of Mr. Clifton's Neck Land from an original made by T.H. in 1755 and copied by G. Washington in 1760 the map includes survey courses and distances of land under cultivation in the 1,800 acre tract and a lengthy list of tenants working the property.

At first glance , the verso of the map seems a disconnected jumble of survey lines. However, careful analysis of the maps shows that it is actually several maps; acreage of two gardens at Mount Vernon done in 1764, as well as a map of land along the creek separating the Mansion House and River Farms purchased from a neighbor, Captain John Posey. Posey purchased this property in September 1759 from Charles Washington, George Washington's half brother. Less than a year later Posey approached Washington with an offer to sell the property and on March 6, 1760 Washington surveyed the property, but upon finding it less acreage than Posey claimed Washington chose not to purchase it at that time. [xii]

The most interesting fact about this map, however, is the missing portion. A comparison of this map a survey of Washington's land on Difficult Run (Fairfax County) dated 1799, indicated that the two seemingly disparate maps were actually part of the same map. Through a wonderful accident of history portions of the same document made their way from Mount Vernon when the Washington Papers were disbursed in back to the collections of the Library of Congress and Mount Vernon, separated by less than fifteen miles.

This discovery extends the "life" of this map from 1760 to 1799 and transforms the map from more than a collection of random surveys into a working document Washington used to record land transaction and surveys for almost 40 years of his life.

In 1766 Washington prepared a map of much smaller portion of the property entitledA Plan of My Farm on Little Hunting Creek. The map covers an 846-acre portion of the river between the Little Hunting Creek and the smaller Poquoson Creek. Both items are among the earliest extant maps of individual farms at Mt. Vernon and among the only colonial estate maps in the Library.

Having secured a place in Virginia's aristocracy with the enlargement and successful management of the Mount Vernon estate, Washington continued to tinker with the field, fences, and perimeters for years to come. He became one of the most advanced "scientific farmers" in Virginia and corresponded with leaders of the English agriculturalist movement. Between 1786 and 1794 George Washington exchanged nearly 30 letters with Arthur Young on the subject of agriculture. This map is a printed version of a manuscript Washington enclosed in a December 12, 1793 letter to Young describing his estate and the rotation of crops. Originally prepared for an 1801 publication[xiii]concerning the correspondence, this printed map describes land under cultivation on the Union, Doque Run, Muddy Hole, Mansion House, and River Farms. The manuscript original is in the Huntingdon Library.

Washington As Land Speculator

Another way Washington sought to secure his place among the elect of colonial society was through the most profitable phase of his cartographic career, that of a land speculator. From his first land acquisitions in 1750 until his death in 1799 Washington would continued to seek out, purchase, patent, and eventually settle his properties. His will, executed in 1800, lists 52,194 acres of land to be sold or distributed in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, Kentucky, and the Ohio Valley. In addition to these properties Washington also held title to lots in the cities of Winchester, Bath (Berkeley Springs), Alexandria, and the newly formed City of Washington. [xiv]

One of the best examples of Washington's lifelong interest in land speculation is illustrated in the fight over bounty lands promised to the veterans of the Virginia Regiment who fought under Washington in the French and Indian War. This episode saw Washington acting on behalf of his fellow veterans as well as actively, sometimes aggressively, staking out his own land claims.

In 1754 Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie, faced with French encroachment into the Ohio Valley, issued a proclamation designed to encourage enlistment in the local militia. In addition to their pay Dinwiddie offered 200,000 acres in the Ohio Valley to be divided among those who enlisted in the fledgling Virginia Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Washington. Unfortunately for the men of the Virginia Regiment who fought under Washington in the Braddock and Forbes expeditions against the French at Fort Duquesne, they would not see the promised land for more than 20 years.

Ironically, Washington's involvement in the French and Indian war as leader of the Virginia Militia is due, in part, to his back country knowledge and map making skills gained from his surveying experience. One year before Dinwiddie called for additional troops to defend the Virginia frontier, Dinwiddie was advised by London to investigate the French encroachment and "require of them peaceably to depart" and if necessary, "drive them off by Force of Arms." [xv]Upon learning that Dinwiddie was looking for someone to deliver the message, Washington actively sought the appointment.

Accompanied by Christopher Gist and Jacob Van Braam, Washington left Williamsburg in October 1753 on the journey to deliver the dispatch, arriving at Fort Le Boeuf (site of Waterford, PA, today)in early December 1753. Only two days after his arrival at Fort Le Boeuf the French commander delivered his response and Washington set off on the 500 mile trip back to Williamsburg arriving on January 16, 1754. Washington summarized his observations in a hastily written report to Governor Dinwiddie who then had it quickly printed in Williamsburg under the title "The Journal Of Major George Washington." The journal was then again reprinted in London thereby catapulting the previously unknown Washington onto the world stage.

Although an engraved map[xvi] prepared by Thomas Jefferys was issued in the London reprint of his Journal, Washington prepared a sketch map of his journey for Governor Dinwiddie. There are three known manuscript versions of Washington's important map, and It is likely that the maps accompanied correspondence from Governor Dinwiddie to his superiors in London. Their significance lies in the fact that, although there were other published maps available to British colonial interests at the time, these maps stand alone as the sole representation of the state of geographical knowledge at the outbreak of the French and Indian War. Taken together with Washington's report, the sketch maps serve as a graphic, if not dramatic, example of the French threat to British interests in the Ohio Valley. The map also contains one of the first cartographic references to building a strategic fort at the junction of the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers, the site of present day Pittsburgh, PA. It is also interesting to note Washington's seemingly inescapable involvement with the beginning of the French and Indian war. He not only volunteered to deliver the message to the French authorities but, perhaps unwittingly, produced a propaganda map highlighting the French threat and even went so far as to be involved in the first skirmish of the war with his ambush of a French detachment in 1754.

Even though he had left the Virginia Regiment in 1758, he became the de facto leader in its struggle to secure title to bounty lands promised for their service. Although the formal end to the world wide war between Britain and France in 1763 gave hope that the land would be granted Washington's hopes were overshadowed by the royal proclamation of that same year (1763) which, among other things, forbade colonial governors from issuing land grants west of the Allegheny Mountains.

Despite the limits imposed by the Proclamation, Washington chose to forge ahead as evidenced by a September 1767 letter to William Crawford, a Pennsylvania surveyor, on the subject of land;

"...I can never look upon the Proclamation in any other light (but this I say between ourselves) than as a temporary expedient to quiet the minds of the Indians. It must fall, of course, in a few years, especially when those Indians consent to our occupying those lands. Any person who neglects hunting out good lands, and in some measure marking and distinguishing them for his own, in order to keep others from settling them will never regain it. If you will be at the trouble of seeking out the lands, I will take upon me the part of securing them, as soon as there is a possibility of doing it and will, moreover, be at all the cost and charges surveying and patenting the same.... By this time it be easy for you to discover that my plan is secure a good deal of land. You will consequently come in for a handsome quantity." [xvii]

Washington, unaware of the scrupulous honesty history would ascribe to him, was clearly willing to take considerable risks in seeking out choice land for himself. In the same letter, however, he warned Crawford "to keep the whole matter a secret, rather than give the alarm to others or allow himself to be censured for the opinion I have given in respect to the King's Proclamation." He closed the letter by offering Crawford an alibi should his behavior be called into question,"All of this can be carried on by silent management and can be carried out by you under the guise of hunting game, which you may, I presume, effectually do, at the same time you are in pursuit of land. When this is fully discovered advise me of it, and if there appears a possibility of succeeding, I will have the land surveyed to keep others off and leave the rest to time and my own assiduity."

In 1769 Governor Botetourt of Virginia finally acceded by giving Washington permission to notify all claimants that surveying would soon proceed and to seek out a qualified surveyor to perform the surveys and Washington arranged to have his friend Crawford appointed the "Surveyor of the Soldiers Land." In the fall of 1770 Washington, Crawford, and Dr. James Craik, set out from Fort Pitt by canoe to explore possible sites for the bounty lands. During the descent of the Ohio River Washington and his companions made notations on the course of the river, islands or obstructions, and the mouths of streams emptying into the Ohio River. In addition, Washington kept careful notes on the "bottom" or level, arable land alongside the river and its suitability for agriculture.

After reaching the junction of the Ohio and Great Kanawha rivers, the present site of Point Pleasant, West Virginia, the party continued up the Great Kanawha approximately fourteen miles. Washington made a brief overland inspection and marked off several trees to serve as boundaries for later surveys. The party then returned to Fort Pitt and eventually Mount Vernon.

Early the next surveying season, (spring 1770) Crawford began to survey the tracts he and Washington identified on the expedition to the Great Kanawha. Eight of these tracts are shown on a composite map drawn by Washington in 1774 which is housed in the collections of the Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. The map, completely in Washington's unmistakable hand was prepared from original surveys done by Crawford and Samuel Lewis between June 1771 and November 1774. Under the initial allotment of land in November 1772 Washington claimed a tract of 10,990 acres at the junction of the Ohio and Great Kanawha, as well as several others between the Great Kanawha and Little Kanawha not shown on this map. Under a second allotment of land in November 1773 and through the purchase of several warrants from other veterans, Washington claimed an additional 8,323 acres along the banks of the Great Kanawha stretching eastwards from Point Pleasant to Charleston, West Virginia. This additional acreage was surveyed by William Preston Surveyor of Fincastle County and Samuel Lewis, Surveyor of Botetourt County. Out of a total of 64,071 acres apportioned on the map 19,383 or approximately 30% was patented by Washington. In 1794 Washington provided a description of these lands in a letter to Presley Neville;

"To give a further description of these lands than to say they are the cream of the Country in which they are; that they were the first choice of it; and that the whole is on the margin of the Rivers and bounded thereby for 58 miles, would be unnecessary to you who must have a pretty accurate idea of them and their value. But it may not be amiss to add for the information of others that the quantity before mentioned is contained in Seven Surveys, to wit: three on the Ohio East Side, between the mouths of the little and Great Kanhawa. The first, is the first large bottom below the mouth of the little [Kanhaw]a containing 2314 acres, and is bounded by the river 51/4 miles. The 2d. is the 4th large bottom, on the same side of the River, about 16 miles lower down, containing 2448 acs. bounded by the River 3 miles. The 3d. is the next large bottom, 31/2 miles below, and opposite, nearly to the great bend containing 4395 acs. with a margin on the river of 5 miles. The other four tracts are on the Great Kanhawa. the first of them contains 10990 acrs. on the west side and begins with two or three miles of the mouth of it and bound thereby for more than 17 miles. The 2d. is on the East side of the River a little higher up, containing 7276 acs. and bounded by the River 13 miles. The other two are at the mouth of Cole River, on both sides and in the fork thereof containing together 4950 acs., and like the others are all interval land having a front upon the water of twelve miles..." [xviii]

In addition to Washington's acreage the map also shows the lands surveyed and apportioned to other Virginia Regiment members; Colonel Joshua Fry, Col. Adam Stephen, Dr. James Craik, George Mercer, George Muse, Colonel Andrew Lewis, Capt. Peter Hog, Jacob Van Braam, and John West. To students of colonial history these names will no doubt sound very familiar. Joshua Fry, for example, was one half of the team which produced the famous 1755 "A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of Virginia. . . "; Jacob Van Braam was Washington's interpreter at Fort Necessity; and Dr. James Craik, Washington's lifelong friend and physician was present at Washington's death in 1799.

One year prior to the journey Washington saw and copied a map of the Ohio Valley while attending an Assembly meeting in Williamsburg. Originally prepared by Dr. Thomas Walker from to illustrate the situation of the Loyal Land Company, the map was submitted as a memorial to the Virginia Assembly on December 13, 1769 to press for extending the western most limits of settlement to a line running north from the Holston River to the junction of the Ohio and Great Kanawha Rivers (present day southwest Virginia to southwestern West Virginia.)[xix]

Unfortunately we do not know if Washington was present when the map was presented to the Assembly, nor if he participated in the debate, or even if copied the entire map. It is also possible that Washington may have added information not present on the original map. What we do know is that 1) Walker and Washington were in Williamsburg at the same 2) that the map was presented and that 3) this was probably the only opportunity Washington had to view the map. It is interesting to note that this map, completely in Washington's hand, was copied while Washington was making preparations for the 1770 expedition to choose tracts of land to be patented of the Virginia Regiment veterans., and that Washington himself patented nearly 20,000 acres in the area.

In 1784 as Washington returned to Mount Vernon from successfully leading the Continental Army, his thoughts again turned to his Ohio Valley lands;

"It has been long my decided opinion that the shortest, easiest, and least expensive communication with the invaluable and extensive Country back of us, would be by one, or both of the rivers of this State which have their sources in the Apalachian mountains. Nor am I singular in this opinion. Evans, in his Map and Analysis of the middle Colonies which (considering the early period at which they were given to the public) are done with amazing exactness. And Hutchins since, in his topographical description of the Western Country, (a good part of which is from actual surveys), are decidedly of the same sentiments; as indeed are all others who have had opportunities, and have been at the pains to investigate and consider the subject. But that this may not now stand as mere matter of opinion or assertion, unsupported by facts (such at least as the best maps now extant, compared with the oral testimony, which my opportunities in the course of the war have enabled me to obtain); I shall give you the different routs and distances from Detroit by which all the trade of the North Western parts of the United territory, must pass."[xx]

In this 1784 letter to George Plater, President of the Maryland State Senate, Washington carefully laid out several routes for shipping goods from Detroit to the Tidewater (Detroit, MI to Norfolk, VA). He argued that the vast resources of the region will eventually find a commercial outlet, and, if left untouched, may be controlled by the "crusty & untowards despositions of the Spanish. "The best way to insure that the inhabitants of the West do not seek Spanish, French, or British markets is to insure that their commerce can reach eastern markets easily by supporting internal improvement companies such as the James River & Potomack Canal Company.

The following distances between Detroit and the eastern seaboard were calculated by Washington according to the "best maps extant,";

Detroit to Quebec (via Montreal) — 955 miles.

Detroit to New York City, (via Albany) — 943 miles.

Detroit to the Tidewater (avoiding Pennsylvania) 799 miles

Detroit to the Tidewater (via North Branch of the Potomack) ñ 663 miles

Detroit to the Tidewater (via the Yohiogheny) — 607 miles[xxi]

The shortest and most practicable route is through Pennsylvania, specifically, down the Youghieny River right past land owned by Washington as seen on his 1780 Map of the land around RedstoneIt is also important to note that the Potomac and James River Canal Companies would directly affect Washington's 20,000 acres along the Ohio and Great Kanawha Rivers.

Washington: "... First in the Hearts of Geographers"?

Clearly, Washington's lifelong associations with cartography, either as a surveyor, map maker, or map user, played a pivotal role in his life. Starting as a pimply faced youth (literally) surveying his garden to a young man enclosing the Virginia back country, and from a young military officer graphically illustrating French encroachment along the British frontiers to a shrewd, calculating land speculator, Washington's familiarity with maps and knowledge of cartography provided him with all the skills necessary to succeed in eighteenth century Virginia society. At the very least this his cartographic associations have left an invaluable and almost untouched resource for historians and geographers alike. For example, a key to understanding Washington is not solely studying his public policy or just his military maneuvers, but understanding the impact his knowledge of cartography played on those public policies or military encounters. One of the more interesting books in Washington's library at the time of his death was Jedidiah Morse's 1789 American Geography. Generally considered to be one of the first geographic works published in America, Morse's American Geography also contains a short biographical sketch of Washington compiled by David Humphreys, an aide to Washington during the American Revolution. This small five-page sketch is the first and only authorized biography of Washington and was published by Morse without attribution. [xxii]

Given Washington's experience taming the western frontiers of Virginia as a public surveyor, the impact of his 1754 map and report documenting his expedition to the Ohio Valley, and his lifelong association with maps, it is quite fitting that Washington be memorialized in the first American geography.

More Maps: