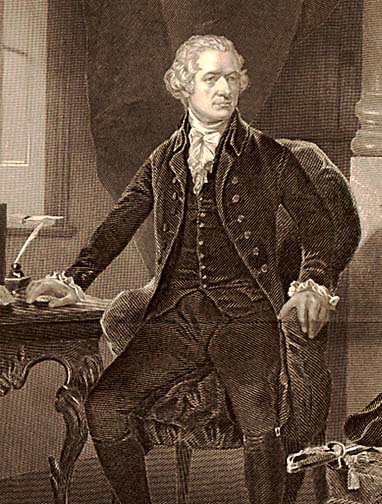

Overcoming Adversity: The Childhood of Alexander Hamilton

By Michael J. Gerson"There are strong minds in every walk of life that will rise superior to the disadvantages of situation, and will command the tribute due to their merit...." Alexander Hamilton, Federalist, no.36, 222

Introduction: Against Overwhelming Odds

A "Resilient Child"

A resilient child is a term that psychologists give to children who seem to overcome multiple personal and family hardships, and survive despite great odds. And survive in the face of great odds is just what Alexander did. Given the experiences that Alexander encountered, we would predict that he would have had numerous difficulties of adjustment in later life. While he may well have struggled with his inner demons, the story of Alexander Hamilton is the story of a multiply challenged youngster who overcomes adverse personal and family circumstances to attain accomplishments of legend.The lessons people learn from family relationships:

Beliefs and attitudes about personal and family relationships are learned in our family of origin. We learn important emotional and behavioral lessons from observing how our parents engage each other and experiencing how they interact with us. Some of the lessons Alexander learned can be discerned by examining the family background and experiences of his parents.Alexander's Extended Family

Historical records, original writings, historical and biographical accounts of Alexander Hamilton allow his family to be traced as far back as Alexander's grandparents. In contrast to the style in which he was raised, a legacy of wealth and education was present among early Hamilton forebears. Family dysfunction, however, is not indemnified by either wealth or education. In the case of Alexander's family tree, wealth, education and family dysfunction seem to reside in tandem.The Maternal Side of the Family

The island home of Alexander Hamilton's Forebears

Alexander's maternal grandfather, John Faucett, was a French Huguenot who had fled to the British West Indies Island of Nevis in about 1658, sometime after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (Hendrickson I 7). He became a physician and a gentleman farmer. John Faucett had been married before, also to a woman named Mary, prior to marrying Alexander's grandmother. John and his first wife had one child, a daughter named Ann. His mother's half-sister and Alexander's only maternal aunt, Anne was born in 1714, fifteen years before the birth of Alexander's mother. (Hendrickson, Rise & Fall 7)

It is thought that the first Mary died, perhaps in childbirth, but specific information is lacking (Flexner 8-9). What is known is that in 1718, on the Island of Nevis, John Faucett married for the second time. His bride, Mary Uppingham, according to Flexner, and Mary Uppington, according to Hendrickson (Rise & Fall 7) was twenty years or more his junior (Hendrickson, Hamilton I 7).

The island home of Alexander Hamilton's Forebears

Alexander's maternal grandfather, John Faucett, was a French Huguenot who had fled to the British West Indies Island of Nevis in about 1658, sometime after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (Hendrickson I 7). He became a physician and a gentleman farmer. John Faucett had been married before, also to a woman named Mary, prior to marrying Alexander's grandmother. John and his first wife had one child, a daughter named Ann. His mother's half-sister and Alexander's only maternal aunt, Anne was born in 1714, fifteen years before the birth of Alexander's mother. (Hendrickson, Rise & Fall 7)

It is thought that the first Mary died, perhaps in childbirth, but specific information is lacking (Flexner 8-9). What is known is that in 1718, on the Island of Nevis, John Faucett married for the second time. His bride, Mary Uppingham, according to Flexner, and Mary Uppington, according to Hendrickson (Rise & Fall 7) was twenty years or more his junior (Hendrickson, Hamilton I 7).

Women of Influence:

Mary Faucett, Alexander's maternal Grandmother, was at the forefront of the powerful women who influenced Alexander's emotional and behavioral development. While women of that era were reputed to be quiet, reserved, and reticent, this was not the case with Mary. Independent, controlling, and assertive, she was described by her grandson many years later "as a woman of beauty and charm, and ambitious and masterful as well." (Hendrickson, Hamilton I 8) His grandmother set a tone and style that was emulated by Alexander's mother. In a manner that was unusual for that era, Alexander's ambitious grandmother refused to accept domination from a male, and was not about to settle for a loveless, conflict-ridden marriage. Ambitious and primarily considerate of her own needs, Mary never hesitated to place her personal desires first when making personal and family decisions. Rigid, stubborn, and hardheaded, when facing adverse situation, she would never become daunted. She possessed a restless propensity to relocate from place to place, and was continually searching for a life style that always seemed to elude her grasp. Dreaming of great possibilities, and never hesitating to manipulate situations, Mary was determined to seek a better life than the one she believed she had. Despite the personal financial difficulties that this move would create, Mary's stubborn determination propelled her to leave her husband. Financial adversity did not deter her, and she worked as a seamstress to support herself and her daughter Rachel. This personal and behavioral pattern was modeled for her daughter Rachel. It was to be a factor in her daughter's attraction to Alexander's father and was a behavioral pattern that was to be repeated by her daughter in the next generation.Alexander's Mother:

John and Mary Faucett had a child who died in childbirth three weeks prior to John's marriage to Alexander's grandmother. John and Mary's second child was Alexander's mother Rachel Faucett, who was born in 1729 on Nevis (Hendrickson I 7). Rachel's birth was followed by the arrival of five siblings. Neither financial comfort nor professional status could shield the Faucett family from the deaths in infancy of all their children except Rachel. When Rachel was seven years old, she witnessed the death of three of her siblings (Flexner 9) in a single month. Tragedies call for people in a family to support each other emotionally, and to help each other move on with life. This is especially true for parents who have lost a child. These parents must take emotional care of other children in the family while still involved in their own grief. Rachel's parents were unable to provide this support for each other or for Rachel. As with many families who experience the death of a child, the stress generated by such a tragedy multiplies any stress that might have already existed in the family. Rachel's parents would argue and fight continually. From the time she was a very young child, Rachel was forced to live with continual family strife and tension.Alexander's Grandparents Separate

After twenty-two years of fighting, arguing, and continual tension, Alexander's maternal grandmother decided that she wanted to leave her husband. In that generation at that time, this was a very unusual decision. Divorce or marital separation were not even legally recognized concepts, and. Alexander's grandfather would not agree to separate. As his grandmother soon discovered, it was very difficult for a woman to obtain a marital separation if her husband did not fully agree to it. His grandfather's refusal to agree to a separation caused even more fights and arguments. The level of tension that filled the home of eleven-year-old Rachel proceeded to escalate. We can surmise that Rachel was likely caught in this net of conflict that enveloped her parents. Faucett family dynamics make it likely that her dominant mother, in alliance against her father, drew Rachel into the conflict. We can further guess that this conflictual family situation caused Rachel significant emotional discomfort. Knowledge of Rachel's future relationships might lead us to conclude that she resolved to never allow herself to be so dominated by anybody, least of all a man. At that time, a bride would give a certain amount of money or property or other material goods to the husband as a dowry. This traditional dowry would become part of the marital couple's financial assets. Rachel's mother reasoned that since she had brought property to the marriage, she was entitled to a settlement that would allow her to live comfortably on her own with her daughter. This was not an unreasonable assumption, and reflected what the Courts in other separations commonly provided. In that era, if a couple were legally separated, a wife was entitled to the return of her dowry upon the death of her husband. In the case of the Faucett's, this would have amounted to about 1/3rd of the estate. Her husband thought otherwise, and would not agree to a financial settlement. As the marital tension continued, Alexander's grandfather began to relent. However, he refused to provide his wife with a financial agreement that would allow her to receive a share of the family's finances.The Separation Agreement:

After a long period of fighting and arguing, in a manner that is strikingly contemporary, the Court instituted a financial settlement. This settlement was the first in a series of burdensome and oppressive legal decisions that were to plague the Hamilton family through the next generation. In order to be legally allowed to leave her husband, Alexander's grandmother had to agree to renounce all claims to the dowry that she had brought into the marriage. The Court ruled that his grandmother was to receive an annual amount of money from her former husband year that might (or might not) eventually total 1/3rd of the total estate on the day of the separation. This annual amount was not even enough for mother and daughter to live much beyond poverty level (Flexner 10). Nevertheless, Alexander's grandmother wanted out of the marriage very badly. So, in 1740, when Rachel was 11 years old, she accepted the agreement devised by the Court, and the couple was formally separated.The Faucett family home on the Island of Nevis

Moving to St. Croix

Immediately upon obtaining the legal separation, Mary and her daughter Rachel left the Island of Nevis and the family estate. For five years, Rachel and her mother lived quietly on the Island of St. Kitts (Hendrickson, Hamilton I 8). Her mother eked out a meager existence by hiring out her slaves and by taking in work as a seamstress. Rachel never saw or spoke to her father.

In 1745, when Rachel was 16, her father died, willing her property that he owned on St. Croix. (Hendrickson Hamilton I 8) Surprisingly, he left nothing to his daughter by his first marriage, Ann, or to his grandchildren, Ann's children. We do not know why. Rachel was also appointed executrix of her father's estate, and she and her mother immediately moved back to St. Croix from St. Kitts to manage her inheritance.

Immediately upon obtaining the legal separation, Mary and her daughter Rachel left the Island of Nevis and the family estate. For five years, Rachel and her mother lived quietly on the Island of St. Kitts (Hendrickson, Hamilton I 8). Her mother eked out a meager existence by hiring out her slaves and by taking in work as a seamstress. Rachel never saw or spoke to her father.

In 1745, when Rachel was 16, her father died, willing her property that he owned on St. Croix. (Hendrickson Hamilton I 8) Surprisingly, he left nothing to his daughter by his first marriage, Ann, or to his grandchildren, Ann's children. We do not know why. Rachel was also appointed executrix of her father's estate, and she and her mother immediately moved back to St. Croix from St. Kitts to manage her inheritance.

Rachel Gets Married

In St. Croix, Rachel and her mother were introduced to a local businessman named John Lavien. Despite his looks, manner, and fine clothing, Lavien was an unsuccessful merchant, characterized by Flexner as "incompetent, his business career moving steadily downward" (13). Some of Lavien's business dealings were with John Lytton, a relative of Rachel's on the Fawcett side. John Lytton was reportedly a wealthy merchant, and it is likely that Lavien believed Rachel and her mother to be wealthy, like their Faucett relatives. Lavien began to make a play for the attractive and outgoing Rachel, hoping to marry Rachel in order to obtain entrance into what he believed to be a very wealthy family. Lavien's courtship of Rachel was likely hastened in view of crop failures that caused him to suffer staggering financial losses around the time of their engagement (Hendrickson, Hamilton I 9). Rachel's mother had always been impressed with wealth. Her propensity to suspend judgment and move toward money had likely been a motivating factor in her own failed marriage. As shrewd as he was, Lavien was very much aware of Rachel's mother's overriding interest in money, and her attraction to moneyed people. He was determined to capitalize on her beliefs and he accomplished this very well. Rachel's mother was very impressed by Lavien's style of dress, and his talk of his business success. Hendrickson notes the irony here. (Hendrickson Hamilton I 9) "Each probably had rising expectations that the other was richer than he was or she was, which neither did anything to dispel before the wedding day." It was not only the financial attraction that motivated John Lavien's interest in Rachel. Lavien was smitten with Rachel's physical appearance and personality, apparently an easy and understandable attraction. According to McDonald, Rachel was "a woman of great beauty, brilliancy, and accomplishments" (6). Her grandson, Allan McLane Hamilton as well, described Rachel as " a brilliant and clever girl, who had been given every educational advantage and accomplishment, and had profited by her opportunities"(9). We don't really know what Rachel thought of John Lavien at the time, but it apparently did not much matter. Rachel's mother, Mary, in addition to being "ambitious and masterful, had very decided ideas of her own regarding her daughter's future" (Hamilton 8). And Lavien was a perfect fit for the script that Rachel's mother envisioned, leading her to "force" Rachel's marriage to this seemingly wealthy and well-dressed suitor (Hamilton 9). This was 1745; Rachel was sixteen years old, John Michael Lavien, twenty-eight. Within a year, Rachel and John had a child, Alexander's half-brother, Peter. Within that time as well, the financial circumstances of the family became clear. It was now apparent that not only was Lavien not wealthy, he was a very poor businessman whose commercial efforts were characterized by "trouble, failure, and decline" (Hendrickson, Hamilton I 9).Rachel's reaction to an abusive husband

People learn lessons about relationships and families from their parents. They learn how to discuss differences, how to argue, and how to resolve conflicts. Sometimes at a level that may be below their level of awareness, they use their parent's relationship as a model for how to behave in their own marriage. This was clearly true of Rachel. One of the lessons that Rachel learned from her mother was that there are options to a very poor marriage. And she was soon to make use of this lesson. According to her grandson, "the marriage was evidently one of very great unhappiness from the beginning", and Lavien treated his wife "cruelly." (Hamilton 9) Rachel's reaction to the stress and cruelty in her relationship with her husband was predictable. Given what she had experienced and what she had learned in her family of origin, she was not about to tolerate increasingly abusive behavior from her husband. As Lavien became increasingly "vindictive", (Flexner) "it became a hateful marriage, and she began to consort openly with other men" (Hendrickson Hamilton I, 9).Rachel Goes To Jail

As Rachel had previously learned through her mother's experience, the Courts did not treat women as equals in their relationships with men. Women were basically viewed as the property of their husbands, and were not afforded many individual rights. Lavien vowed to teach Rachel a lesson that, he believed, would force her to do whatever he wanted her to do. Not hesitating to make use of the way the law was structured, he pressed charges against Rachel, accusing her of "indecent and very suspicious behavior," i.e. adultery, and presented his case to the local authorities (McDonald 6). Charged by her husband as having "twice been guilty of adultery", was sentenced to jail (McDonald 6). This was seven years before Alexander's birth. As with any other child however, Alexander would learn from his parents to hold certain attitudes about the law and the courts. Thus, the ramifications of his mother's treatment at the hands of the Law were to be felt many years later, as it surely informed Alexander's thinking and behavior as a legislator, journalist and prominent attorney.Repeating A Pattern: Rachel Leaves Her Husband

After a time, John decided that Rachel had learned her lesson. He believed that she would not want to return to jail, and that she would be so afraid of having to do so that she would obey him, and do whatever he wanted. So Lavien agreed to have Rachel released from prison. But Lavien had miscalculated. Rachel repeated the pattern she had learned from her mother. Rather than stay and accept further domination, accompanied by her mother, she ran away. She left her son Peter with his father.Repeating Family Patterns: Leaving for St. Kitts

As they did years ago when Mary left her husband, as soon as Rachel was released from prison, she and her mother took off, once again in abject poverty. This time they were bound for the island of St. Kitts (Hendrickson Hamilton I 10). Despite all that they had been through together, Rachel and her mother experienced increasing conflict in their relationship and they soon went their separate ways. A will that Mary executed in 1756 on the Island of St. Eustatius indicated that she had lost touch with her daughter (Flexner), but that she was deeding her three slaves to a friend who was to pass them on to her daughter upon her death (Hendrickson Hamilton I 10). Once again, the fragility and tenuous nature of emotional connections in the family is demonstrated. This lesson will impact Alexander's emotional functioning in the years to come. While her mother apparently left the Island after they went their separate ways, Rachel remained on St. Kitts. By then, she had met the man who was to become her new lover, James Hamilton.Abandoning A Child

But what about Peter? This was not a situation where Rachel could make periodic visits to her son. She could not even hope to follow Peter's growth and development second hand from someone who remained on the Island. This was a cut-off of the most severe kind; a mother was to lose all contact with her son. How difficult was it for Rachel to abandon a child? There is no way for us to know for sure, but from what we know of Rachel, and what she learned from her mother, the abandonment of Peter is not totally unexpected. Like her mother, Rachel was independent and determined. Rachel's early family experience had taught her to view relationships as impermanent, and to view life as tenuous. This was a woman who had witnessed the death of five siblings, three in one month. As a young girl, she was forced to abandon a life of comfort and take flight when her parent's marriage ended. She was propelled into a loveless marriage by a mother who placed more emphasis on wealth and status than she did on her daughter's marital happiness. Rachel had apparently learned to become a mother who was able to abandon her son.Abandonment's Impact on Alexander

The personal security that a child feels is to a great extent dependent on the feelings of permanence that the child receives from its' parents. Though he was yet to be born, Alexander was not to escape the emotional ramifications of his mother's abandonment of his older brother, Peter. While Rachel may well have had reasons of which we are not aware, the act of abandonment would be a stark demonstration to Alexander of the behavior of which his mother was capable. The seeds for the feelings of deep insecurity that plagued Alexander throughout his life, and which motivated much of his behavior, were thus planted well before he was even born.The Paternal Side of the Family

Alexander's paternal forebears could be considered a classic aristocracy. The Hamilton's were landowners and lived on the same land for centuries. The family lineage is strewn with various Royal titles including Viscounts, Barons, Dukes, and other extinct peerages (Hamilton I 6). Alexander's paternal grandfather, his namesake Alexander Hamilton, was the scion of this wealthy, land owning family with aristocratic roots and titles of nobility that can be traced back several centuries. His grandfather rented out this land in the county of Ayreshire, in Scotland, to shepherds. As a way of comparing the relative wealth of the two sides of Alexander's family, the annual rents that Alexander Hamilton Sr. collected from his shepherd tenants amounted to more than a hundred times the annual amount that Mary Faucett had been awarded in her separation from her husband (Flexner, 16). In 1711, Alexander's grandfather married Elizabeth Pollock, Alexander's paternal grandmother. On the Pollock side, titles and Royal citations were present as well, and could be traced back six hundred years. The Pollock family standing is indicated in a 1702 proclamation by Queen Anne, in which she declared Alexander's paternal great grandfather, Sir Robert Pollock as Baronet of Nova Scotia. The marriage of Alexander's paternal grandparents initiated the kind of financial merger that would make proud the most aristocratic Old World European family. Elizabeth's father, Sir Robert, provided Elizabeth a sizable dowry to bring to the marriage. As an indication of the dowry's size, it was said to be seven times as large as the annual amount collected in rent by Alexander Hamilton Sr. (Flexner 17), which as we remember, was itself more than a hundred times larger than Mary Faucett's annual alimony. His grandparent's marriage thus established even further the financial strength of Alexander's lineage. But Alexander's father, as we will see, did not let the family's financial strength, Royal titles, land holdings, or aristocratic status stand in the way of his relentless slide down the economic ladder.Works Cited

Brookhiser, Richard, Alexander Hamilton, American. (New York, 1999). Flexner, James Thomas, The Young Hamilton (New York, 1978). Hamilton, Alexander Federalist, no.36, 222 Hamilton, Allan McLane, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, (New York, 1911). Hendrickson, Robert, Hamilton I, (New York, 1976). Hendrickson, Robert, A., The Rise & Fall of Alexander Hamilton, (New York, 1981.) Larson, Harold, Alexander Hamilton: The Fact and Fiction of His Early Years, William and Mary Quarterly 9 (April 1952), 139-151. Lehrman, Lewis, E., Alexander Hamilton: precocious & preeminent, The New Criterion, V.17, No.9, (1999), 31-36. McDonald, Forrest, Alexander Hamilton, (New York, 1979).Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

Fortnite: Battle Royale Tutors

Accounting Tutors

Ceramics Tutors

IB Social and Cultural Anthropology HL Tutors

PostScript Tutors

College Essays Tutors

IB Philosophy SL Tutors

10th Grade Homework Tutors

Medical School Test Prep Tutors

Biology Tutors

Middle Low German Tutors

ACT Tutors

12th Grade Tutors

German Studies Tutors

Scientific Programming Tutors

Pre AP English Literature Tutors

Adult ESL Tutors

SIE Tutors

Math Tutors

Common Law Tutors

Popular Test Prep